Cecil Beaton

Portrait by an artist.

Cecil Beaton, like the Gershwin brothers or Cole Porter, sums up an era of carefree elegance, all depicted in black and white, of course. Beaton is the definitive photographer of glamourous portraiture. He’s influenced every celebrity snapper who’s come after him. At a retrospective at the National Portrait Gallery in London much of the work displayed was over 50 years old, yet still so powerful that audiences flooded in. The only NPG show with better attendance figures than the Beaton retrospective was the work of the popular modern celebrity photographer Mario Testino, who cites Beaton as “a great inspiration for my work”.

Beaton was a restless creative spirit. As well as a photographer he was an illustrator, painter, writer, set designer, and famously a costume designer. He won one Oscar for his costumes for the film Gigi, and another for the unforgettable costumes, those fabulous hats, he created for My Fair Lady. Audrey Hepburn never looked more beautiful. Despite these achievements, his photographs are what people remember first and seeing over a 100 of them together packs a powerful collective punch. These are the faces of many of the cultural heroes of the past century. Beaton lived only 76 years but the breadth and volume of his work suggest an extremely vigorous creative life.

Beaton was a confirmed snob and used his camera to insinuate himself into society’s upper echelons and impress Hollywood’s biggest stars. He began photographing society girls, but his ability quickly led him to greater challenges. He won not only access to Judy Garland and Greta Garbo, but to Coco Chanel, Pablo Picasso and Andy Warhol. His photo of Harold Pinter is as relaxed and revealing as the one of Robert and Ethel Kennedy. Gertrude Stein looks as ferocious as Winston Churchill.

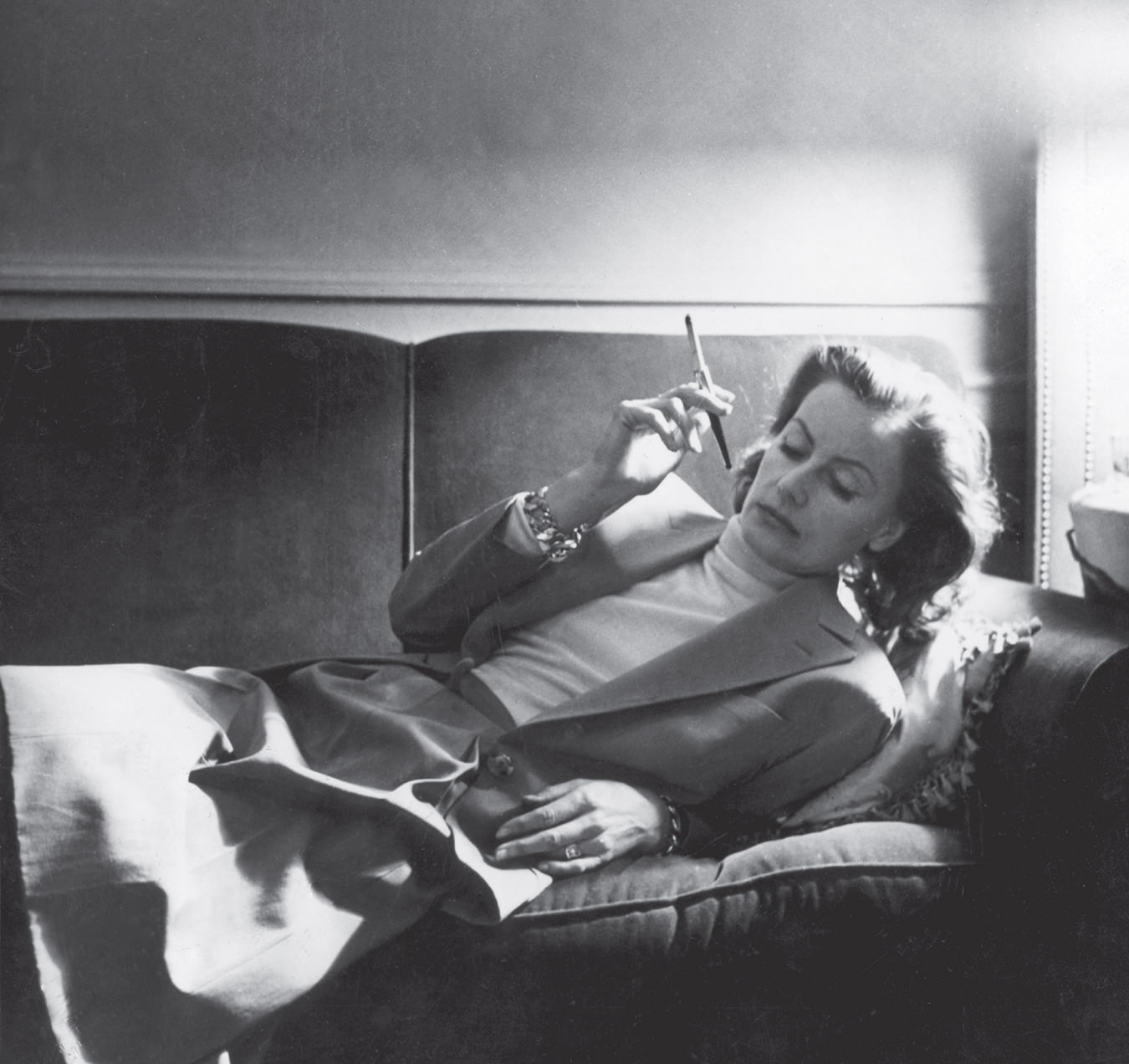

Beaton thrived in the reflected fame and the open doors his success gave him. After all, most successful photographers get to shoot 10 or 20 famous people, usually all from one discipline, in a lifetime. Beaton snapped triple that number. Yet his pictures suggest that his heart lay in photographing icons like Marlene Dietrich. This is where he deployed some of his cleverest techniques. He loved the theatre (he was also a playwright) and saw the natural drama in life. So he developed devices which allowed stars to be the personas they’d created, the version of themselves they’d project on the screen, the one designed to protect their human selves.

Beaton said a fashion photographer’s job was “to stage an apotheosis”, which is an act of worship, wherein the subject defies death and, forever young, achieves a god-like status. The sitter is a part of the whole, their image as controlled as the set. As Terence Pepper, the show’s curator, says; Beaton’s work is “all theatrical”, citing his composition as “the great thing”. Beaton created stage sets for his subjects, flatteringly lit them from behind, often organizing the props and making the backdrops himself. After the photo was taken the sitter’s image was adjusted in a careful, delicate process. Today such changes are achieved digitally, but Beaton, who falsely claimed an amateur status about all things technical, hired studio assistants for the slow laborious job of working on the negatives. They etched out the lines on the subject’s face, eliminated downward aging shadows, erased stubble on a chin, sculpted thinner arms, carved a smaller waist or brightened the eyes of the sitter. Beaton made sure that the camera bestowed what he called “a glorious halo” on the people it portrayed. Beaton photographed them as they wished to be seen, and they adored the results.

Beaton’s subject is art rather than life. Marlene Dietrich is photographed next to a stone effigy and it’s utterly apt. An attempt to create an everlasting monument to the passing nature of beauty becomes a monument to death. Even beauty as ethereal as Dietrich’s turns to stone. The subjects of Hans Holbein’s 16th century paintings look more likely to speak than do the subjects of Beaton’s Hollywood work.

Beaton’s photography creatively bridged the Edwardian world of painted portraits whose function was to bestow status, and early photographs where subjects stood stiffly, as though they were about to be shot literally, with the modern immediacy of film, telephones and telegraphs. It’s a delicate balance and sometimes the marriage was heavenly.

Terence Pepper asserts that Beaton almost single-handedly made the Royal Family glamourous, pointing out that he was the first to take backdrops into Buckingham Palace. He was the perfect person to gently infuse some humanity into the usual stiff depictions of the Royal Family. Fascinated by power, his pictures of the Royal Family during WW2 often gave a casual grace-under-pressure impression. His photos of Princess Elizabeth as a young woman in an army outfit, at ease with the role that awaited her, inspired a nation at war.

You sense that as an artist, he couldn’t help himself. His stagy sentimentality made all subjects prettier. His photograph of a charming little blonde girl in a hospital bed with a bandage around her head became one of the most popular photos of WW2. It was used as a poster for the Red Cross and graced the covers of several magazines.

Even after he’d established a hugely successful career, Beaton continued to experiment. Unlike Yousuf Karsh, whose style never really changed, Beaton’s work appeared more relaxed. He generated interest in The Rolling Stones when he shot them in casual poses. They were thrilled he’d noticed them and they led him into a new world populated by models like Twiggy and Jean Shrimpton and artists like David Hockney. Many of these photos are more lively and charming but they lack the power, that special Beatonesque adoration and stillness, which infuses his early work. The icons become people, more alive, less glamourous and less powerful.

Lovely and luscious as they are, it’s difficult to look at these photographs through modern eyes, and not squirm a little. After seeing dozens of such photos, the cumulative effect is one of the posed and the poseur, a perception underscored by his camp, contrived self portrait, in which the elderly Beaton is wearing 60’s hip clothes and appears to have given himself a total facelift. There’s little joy in many of the subjects; they rarely smile. Perhaps the discomfort is the fault of the modern eye. We’re bombarded with re-shaped and re-jigged images of celebrities who falsely appear casual and breezy. Among the many intriguing charms of such a retrospective as this, is the gentle challenge to re-think our own presuppositions. To see Beaton’s work in some kind of aggregate such as the London Retrospective is edifying, but also provides the challenge that cold comfort provides.

All photos ©Cecil Beaton/Camera Press/PONOPRESSE.