-

The sunburst tiara of 577 brilliant diamonds and many more rose-cut stones, made by Cartier, Paris, for the Tysckiewicz family in August 1921. The centre was once set with a diamond of jonquil colour that weighed over 71 carats. This was subsequently replaced with a large star sapphire. This on the forehead so that the jewelwork was parallel to the line of the brow. The central element is tremblant, responding to the wearer’s every move. (Private collection.)

-

A wreath of twinned sprays of leaves and flowers. Entirely set with brilliant diamonds, the flowers are cleverly suggested with larger brilliant-cut stones that are free-hanging and tremble at the slightest movement of the wearer. Made by Cartier in 1904 and purchased by Mrs. Louise Hill in 1906. (Photo reproduced with the kind permission of the trustees of the late Lord Howard of Henderskelfe.)

-

The pearl and diamond tiara arranged as a series of graduated pinnacles of diamonds, each surmounted by a pearl. Possibly English, c.1900. The jewel is in a fitted case from Cartier but an attribution to the famous firm seems unsafe. The height of the jewel has been increased with a gallery of cultured pearls. (Their Royal Highnesses Prince and Princess Michael of Kent ©Reserved.)

-

A tiara by René Lalique, c.1900, in the form of a swarm of dragonflies pursuing a faceted aquamarine. Their wings are naturalistically represented in plique-jour enamel, and their thoraxes and abdomens are set with diamonds. The jewelled ornaments can be removed from the frame and rearranged so that the bodies of the insects cross one another. They can be worn in this way as a brooch. (Private collection.)

-

The delicate piercing of the wings and the subtle colouring of the enamel can be clearly seen in the detail. (Private collection.)

-

Jacqueline Kennedy, wife of John F. Kennedy, 35th President of the United States. Dressed for a formal occasion, the First Lady had cleverly suggested the presence of a tiara with the antique sunburst brooch. (Wartski, London.)

-

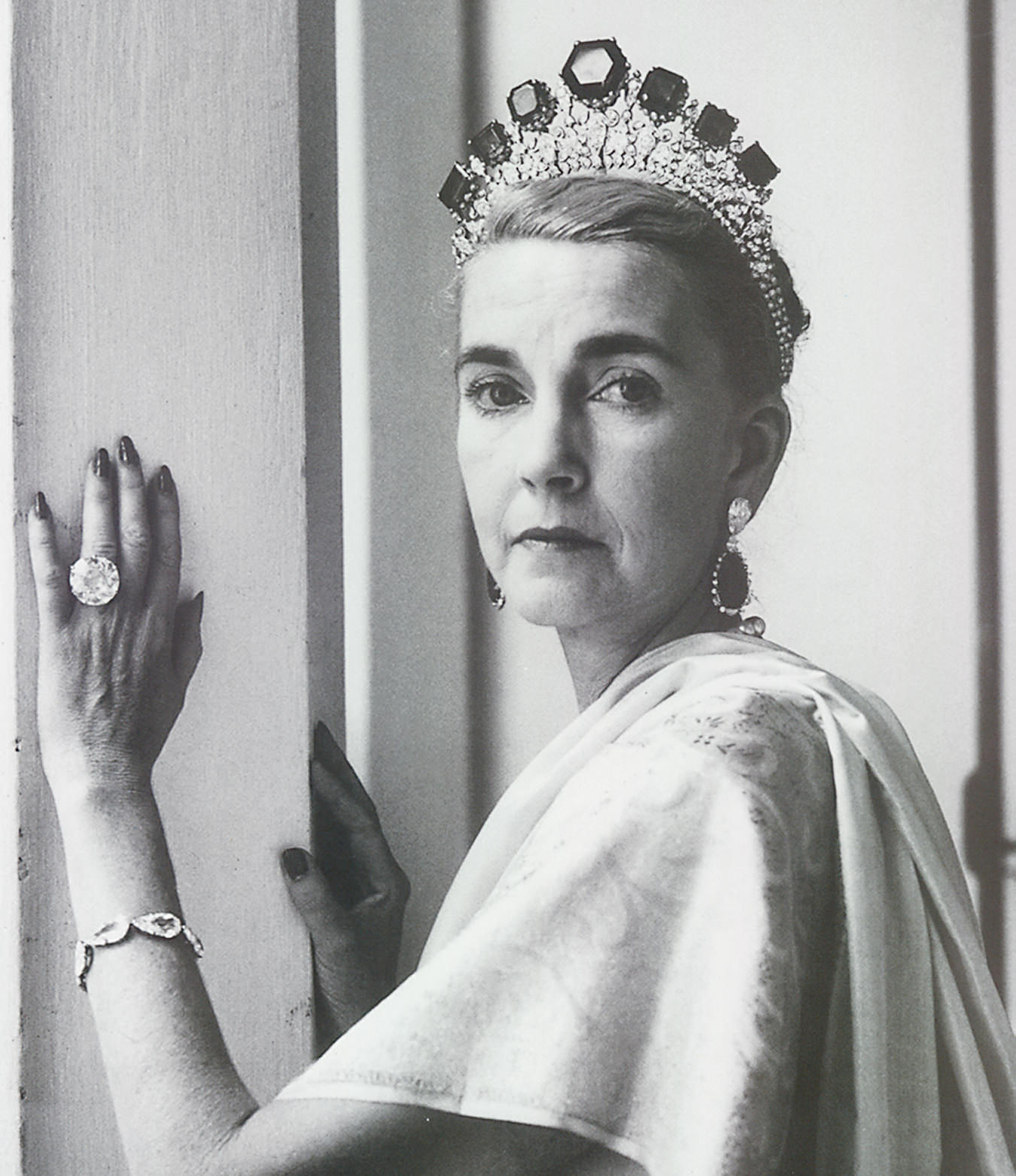

Barbara Hutton, photographed by Cecil Beaton, wearing the emerald and diamond tiara designed by Lucien Lachassagne and made by Cartier in 1947 to accommodate the emeralds that had once belonged to Grand Duchess Vladimir. She is wearing the Pasha diamond as a ring, its weight 40 carats. The Woolworths heiress inherited $28 million dollars before she had reached her teens. (Cecil Beaton archives, Sotheby’s.)

-

Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton photographed by Cecil Beaton at the Proust Ball, given by Baron and Baroness Guy de Rothschild at the Château de Ferriéres. Elizabeth Taylor wore a vast diamond at her neck and her hairline was defined by a diamond fringe necklace. The aigrette is supported by an emerald and marquise-cut diamond brooch. (Cecil Beaton Archive, Sotheby’s.)

-

Diana, Princess of Wales, photographed by the Earl of Snowdon on the eve of the Prince and Princess of Wales’s official visit to Canada. The Princess is wearing the Spencer tiara. (Camera Press.)

-

An enchanting moment caught on camera as the Queen drove in the Irish State Coach to carry out the first State Opening of Parliament of her reign on 4 November 1952. Her Majesty is wearing the Regal circlet of King George IV, the pearl and diamond necklace given to Queen Victoria at the Jubilee of 1887 and the diamond watch that was a gift from the Swiss Federal Republic.

-

Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother photographed by Norman Parkinson in 1975. She is admiring the Empire-style tiara by Boucheron left to her by the Hon. Mrs. Greville. (Norman Parkinson/Fiona Cowan.)

-

A diadem by René Lalique in the form of a mermaid who has surfaced carrying a large opal retrieved from the depths of the sea. Her twinned tails frame opal bubbles carved to represent a shoal of fish. The mermaid’s hair is extended at the back to support the jewel in the hair of the wearer. By René Lalique, Paris, c. 1900. (Musée des Arts Décoratifs, Paris.)

-

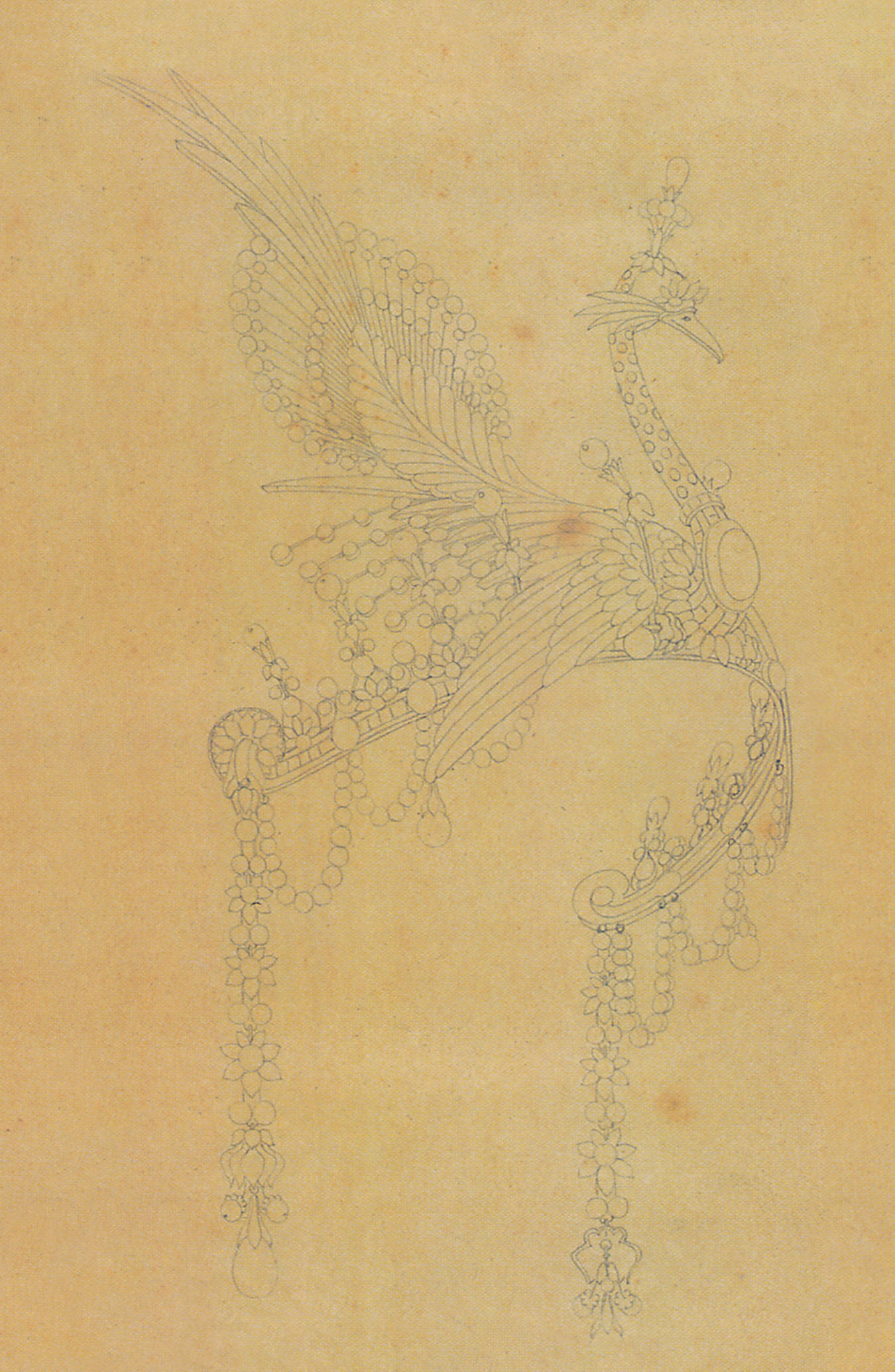

The design for an elaborate tiara in the form of a bird’s head and wings by Camillo Bertuzzi. This jewel was to be set with precious stones cut en cabochon and hung with pearls. Made for Marchesini of Florence in 1872. The elaborate nature of this head ornament suggests that it may have been made for a costume ball. (Vincenzo Melchiori, Esq.)

From Temple to Temple

From Russia to France with love.

This is not a story about tiaras. Not really. Yes, there was a stunningly extensive exhibition at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, a serious elaboration on an unanticipated runaway success show at Wartski’s in London. Yes, certain Crown Jewels were involved. Many pieces personally designed by Cartier, Fabergé, Lalique. Many pieces owned or worn by Madonna, Elton John, Princess Diana, and poor little rich girl Barbara Hutton. But one minute after meeting Geoffrey Munn, tall, stately curator of the exhibit, author of Tiaras: A History of Splendour and “Antiques Roadshow” jewellery specialist, it all becomes clear. You are not looking at diamonds, sapphires, platinum wire, the sum of which amounts to the 200 tiaras on display: you are considering recent history, in design, fashion and politics. One thing, though; the tiaras are more lovely than the history they emblemize, by a long shot.

It is fascinating to know that the crown Elizabeth II bore upon her head for over 40 minutes during her coronation ceremony weighed nearly a third of her entire body weight. It would be nice to think, then, that tiaras ensued from a perhaps stolid tradition of ceremonial ornamentation that eventually demanded a little common sense. Relieve the head of the crown, literally but of course not figuratively; upon it place instead a band, usually reaching from temple to temple, supported, really, by the ears and hair, which still constituted domain and empire. The truth is simpler, and more complex.

Gold wreaths from 350 BC, shaped into olive and branch shapes, are the first diadems, or tiaras. Experts rely on paintings and sculpture to trace the history of ornamental headpieces, and they have been able to go that far back. It took Napoleon and the Empress Josephine to usher in what can be considered, as Geoffrey Munn says, “the beginning of the tiara as we think of it today.” The irony of Napoleon’s lack of dynastic credibility was not absent in his mind, but a spur to creating symbols of endurance and luxury, to reflect his reign and his influence.

Designers were invited to create special pieces, many worn at special occasions. Before long, designers realized this was a mode of expression, and in Russia particularly, it blossomed as a specialty. The kokoshnik, a uniquely Russian headpiece, can be traced back to antiquity as well, but is distinct from Roman and Greek traditions. There are folk beginnings, but the Russian Imperial family gave it a new, and substantially greater, prominence in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. For Fabergé and his followers, who pleased not only royalty but aristocrats of all stripes, it was the beginning of tiara design as both reflection and precursor for larger design trends. There was also a significant move from royalty to private citizens, initiated by Tiffany’s purchase of a vast quantity of the French Crown Jewels, whose uncontested and illustrious provenance created an instant cachet for the American design house and its clients.

For Fabergé and his followers, who pleased not only royalty but aristocrats of all stripes, it was the beginning of tiara design as both refLection and precursor for larger design trends.

Fabergé was on to something good when he set his mind to tiaras, and it was not a complete stretch to see the link between his work and that of Lalique in France, and then from Lalique to Art Nouveau and on to Art Deco (including pieces that actually were modelled after certain key architectural monuments in New York City). Cartier and Boucheron also made significant forays into Russia, all being well right up to the Revolution, when aristocrats fled clinging to their lives and their valuable jewels, which were vehemently vended into a market that nearly collapsed because of the influx of high quality stones.

Munn’s 434 page book, abundantly and carefully illustrated, traces these developments, and is fascinating to read. There is a tiara made by C.F. Hancock for Countess Granville, who accompanied her husband as Queen Victoria’s representative at the coronation of Tsar Alexander II, in 1856. There is the ‘halo’ tiara, made by Cartier for His Highness Aga Khan III, who in turn gave it as a prenuptual gift to his wife. There is the Nur ul-Ain tiara, of old-cut coloured diamonds, made by Harry Winston to become part of the Iranian crown jewels. The list goes on.

What the book cannot do is adequately convey the impact of individual pieces that were on display, likely for one and only one time. What the book also cannot convey is Geoffrey Munn’s droll erudition and simmering passion for his subject. As he pauses before each display case, usually with five to seven directly related pieces in it, he provides a succinct time capsule, placing the objects in their time, relating them to what came before and what ensued. Most interestingly, though, he, like Ronald Winston of the house of Harry Winston, does not actually speak so much about gems and headpieces. He speaks about personalities, historical events, courts and political intrigues, revolution and posterity.

In Geoffrey’s hands, it becomes effortless to understand the monarchy’s central role in the practical and imaginative lives of what used to be called “subjects”. It is like the most glamourous, eventful, weighty soap opera you could imagine, except it all happened, and continues to happen. It is a bit strange to look upon the Spencer tiara, for example. Diana wore it when she posed for a photograph taken by Lord Snowden on the eve of her first Royal visit to Canada. The headpiece looks elegant and luxe when sitting in a display case, but on her head it takes on elements of actual charm, an almost alarming transformation of the inert into something, well, other. In the photo, she sits askance on the throne-like mahogany chair, a subtle forebear of the rest of her life.

Virtually all of the pieces carry a similar weight and transformative quality. The tiaras worn by princesses Margaret and Elizabeth (the woman who would be queen); Dukes in Russia and England; French royalty; and, eventually, American royalty, including Rose Kennedy and her daughter-in-law Jaqueline: all carry with them the unmistakable weight of momentous events and large personae.

The headpiece looks elegant and luxe when sitting in a display case, but on her head it takes on elements of actual charm, an almost alarming transformation of the inert.

Munn strolls through the massive exhibit, extolling the virtues or unpacking the local history of any piece. The designers themselves are high in the firmament of haute design, and Munn can explain which master artisan did what and for whom. That Boucheron, Cartier and Lalique were influenced by the Russian Fabergé, and began creating pieces in Russia for Russians, makes the intricacies of design development even more enticing. He pauses before a display case of tiaras closely based on the kokoshnik, and mutters pretty much to himself, “stunning, really.” He explains in his theatrical voice replete with gesture and selective emphasis: “The piece far right is based on pieces in favour at the Romanov Court. Set with 280 brilliant-cut diamonds, and set against blue enamel, it was created by Chaumet, in Paris. Purchased by the second Duke of Westminster for his wife, Constance Cornwallis-West, for the meagre sum of £375. One wonders how, but it did indeed disappear from the family’s possessions, only to be re-acquired by the present Duke. And so it goes with many of these pieces.”

What also goes is what happens to many of the haute design pieces that used to participate in the Diamond International Awards. They are briefly on display, then disassembled, never to be seen in their entirety again. While the number of tiaras on display for this exhibition made experts’ pulses pound, the number of equally valuable and important pieces that now exist as small components spread over a kind of jewel diaspora far surpasses it. When you think about it, that is exactly what you might expect; the set stones that emblemize history and those who participated in it exist only in small portion, just as what is remembered is only a fraction of what actually transpired. This, too, Geoffrey Munn muses on: “pieces that were believed to have dramatic histories were considered particularly desireable. But one wonders how well documented the drama was, and how many pieces were seriously undervalued, if that were the criteria, and indeed how many are simply lost forever.”

London these days is making a serious effort not to forget. Wander any little street from, say, Hyde Park to Westminster Abbey. Foot-square white on blue ceramic plaques are posted on the walls of various flats and walk-ups, commemorating the notables who once lived there. The array of monuments, Buckingham Palace, the Tower of London, and so on, are clustered reasonably close together for the most part, but beyond them the city sprawls and hugs, as it always has, the Thames.

The River Café sits well out, at the Thames Wharf, Rainville Road, and a cab ride there allows for a sample of the gentrified London that accommodates the shocking cost of living quite well. Sitting there, overlooking the river and an elaborate historical building renovation on the opposite bank, it may be the wine that makes you think, just for a moment, that time does somehow adhere to objects, and that history is thereby forced to repeat itself. The wine, or reading Peter Ackroyd’s Hawksmoor too closely. Still, everything Dickens noted seems to be freshly on parade today. No amount of Versace, Phillip Treacy, Kevin Coates and Vivienne Westwood tiaras can create an escape route from the past, from Marie Antoinette, the poor little rich girl, Lady Astor, Princess Di, Queen Elizabeth and all her remarkably look-alike blood relatives. Might just as well have an espresso, and ruminate on what the river has washed over in its day.