-

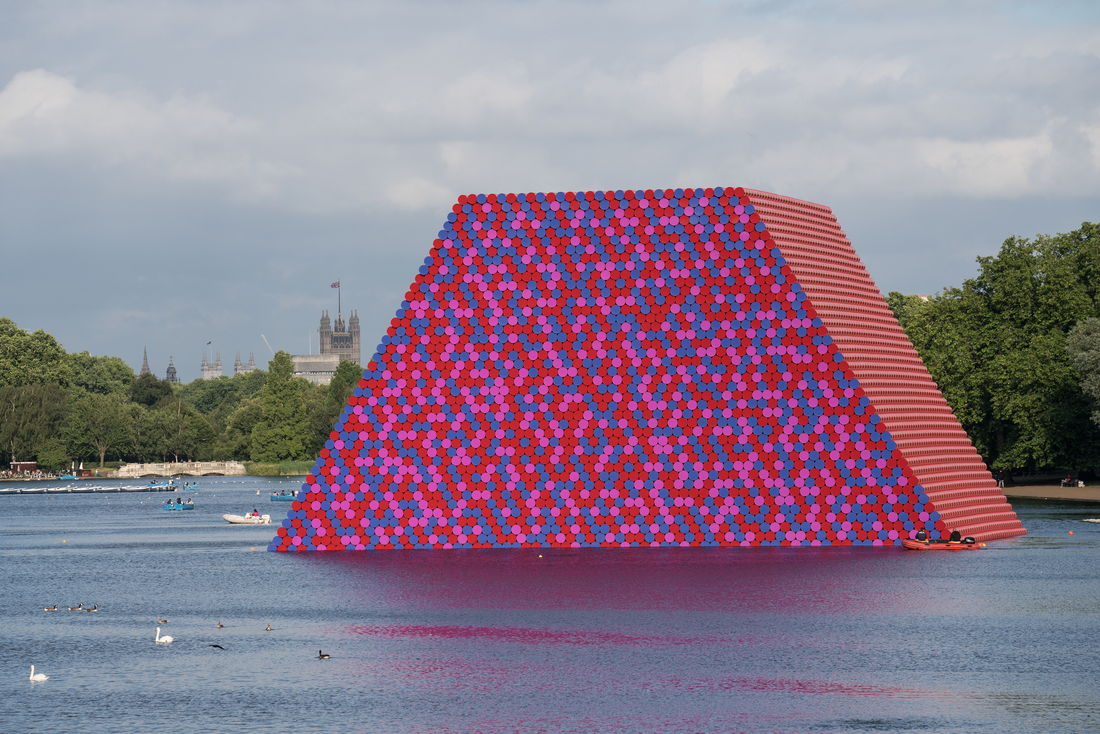

Christo with The London Mastaba on the Serpentine lake at Hyde Park.

Photo by Tim Whitby/Getty.

-

The floating trapezoidal structure is made up of 7,506 barrels.

The London Mastaba, Serpentine Lake, Hyde Park, 2016-18. Photo: Wolfgang Volz © 2018 Christo.

-

Christo has spent a lifetime creating truly monumental pieces of environmental art.

Photo by Wolfgang Volz provided by the Serpentine Galleries.

-

Christo and Jeanne-Claude, The Floating Piers, Lake Iseo, Italy, 2014-16. Photo by Wolfgang Volz, © 2016 Christo.

-

Christo and Jeanne-Claude, Surrounded Islands, Biscayne Bay, Greater Miami, Florida, 1980-83, Photo by Wolfgang Volz, © 1983 Christo.

-

Christo and Jeanne-Claude, Wrapped Reichstag, Berlin, 1971-95. Photo by Wolfgang Volz, © 1995 Christo.

-

Christo and Jeanne-Claude, Valley Curtain, Rifle, Colorado, 1970-72. Photo by Wolfgang Volz, © 1972 Christo.

-

Christo and Jeanne-Claude, Wrapped Coast, One Million Square Feet, Little Bay, Sydney, Australia, 1968-69. Photo by Shunk-Kender, © 1969 Christo.

-

Christo and the London Mastaba, credit Tim Whitby, Getty.

-

The London Mastaba, credit Tim Whitby, Getty.

Christo Takes London

A floating structure is set for Hyde Park.

The achievement, says Christo, was less the engineering feat and more the fact that anyone would let him do it at all. In 2016, the Bulgarian émigré artist—full name Christo Vladimirov Javacheff—created a bright yellow floating walkway from the shore of Italy’s Lake Iseo to the island at its centre. Some 250,000 people turned up in the first five days to walk on water. “But building a structure like that isn’t difficult. These works don’t have the complexity of, say, a skyscraper or a bridge. The difficulty,” he says, “is finding a country that will let you put a fabric walkway over depths of more than 90 metres without also putting up rails.”

Christo, 82, has spent a lifetime creating truly monumental pieces of environmental art. He’s the artist who, in 1969, used a million square feet of synthetic fabric to wrap 2.4 kilometres of Sydney’s coastline; who in 1995 wrapped the entire Reichstag in a polypropylene sheet; who in 1972 hung over 200,000 square feet of orange fabric across Rifle Gap in Colorado; and who, for the last 41 years, has been trying to build The Mastaba in the desert near Abu Dhabi, which would be the world’s largest sculpture. (For much of his career, Christo collaborated with his late wife, Jeanne-Claude Denat de Guillebon, who passed away in 2009.) A Christo work is typically years in the planning, yet is on display to the public, for free, for little more than a week or two.

“[Each work] is precious for being brief, which is true for everything, really,” Christo explains. “These days, we’re bombarded with the banality of things. Yet the fact is that you can’t repeat the moment. It’s here and then it’s gone. And we never repeat a work. We’ve realized 23 projects over 50 years, but haven’t managed to get permission for 36 others. But that’s not bad considering we’re dealing with the real world.”

A Christo work is typically years in the planning, yet is on display to the public, for free, for little more than a week or two.

Dealing with the real world is an arduous process. It took 23 years and three appeals before a vote in the German parliament finally gave permission for Wrapped Reichstag; and since Christo is adamant that the works not be part of commercial gain, he declined the Three Tenors’ request to perform in front of one creation. He recently halted a planned work in Colorado when he realized it would mean operating with the Trump administration—and he’d already spent $15 million (U.S.) on it.

And Christo is the one bankrolling these projects. He prefers to operate outside the commerciality of the art ‘system’, as he calls it, selling preparatory works to a loyal group of collectors to fund the final piece, and using a repository of works stored in Basel to acquire lines of credit from Swiss banks.

“I escaped from Bulgaria when I was 21 and was eager to be an artist away from communist oppression, and wanted to do what all artists want to do: to be outside of any system that uses me or wants control. Besides, I want people to walk on these works, touch them, feel them. And despite their scale, I think they’re very intimate. What we do is more like urban planning.”

This summer, Christo will install The Mastaba (Project for London, Hyde Park, Serpentine Lake) a floating trapezoidal structure made up of 7,506 barrels on the Serpentine lake in Hyde Park. It’s in conjunction with an exhibition of Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s realized and unrealized projects, bringing together sculptures, photos, and drawings spanning more than 50 years at the nearby Serpentine Galleries from June 19 to September 9.

_________

Never miss a story. Sign up for NUVO’s weekly newsletter, here.