Scalawags: Bata Kindai Amgoza ibn LoBagola

The imposter.

Finding these scalawags along the back pages of history is quite an adventure, and during this pursuit I have come across some exceedingly strange individuals, as you will know should you have previously chanced upon these pages. Although I delight in their exploits, they rarely surprise me.

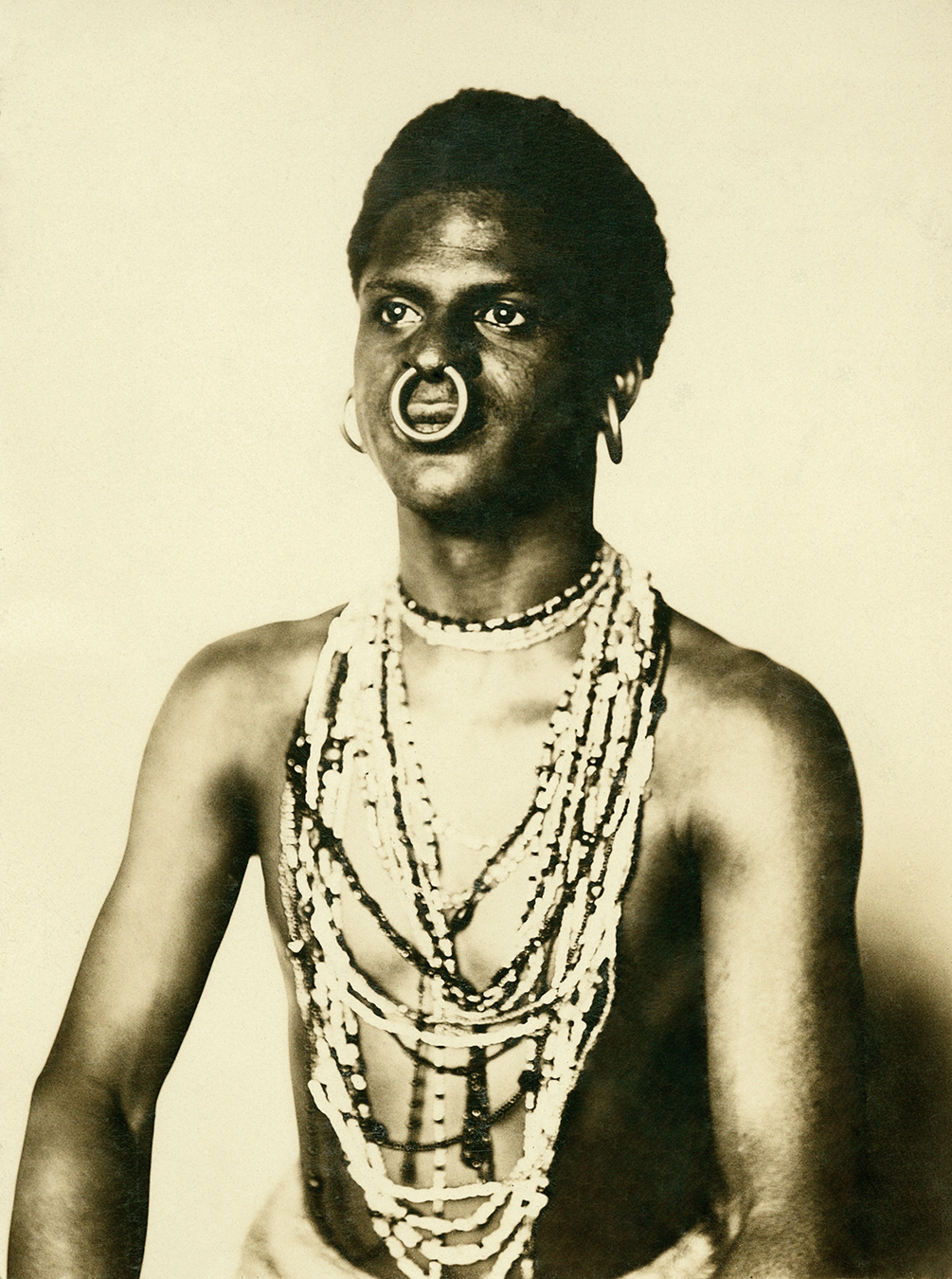

He called himself Bata Kindai Amgoza ibn LoBagola, and in the frontispiece to his autobiography LoBagola: An African Savage’s Own Story, he described himself as “a black Jew, descended from the lost tribe of Israel, a savage who came out of the African bush into modern civilization and thenceforth found himself an alien among his own people and a stranger in the twentieth century world.”

As his story goes, one day when he is nine years old (which would make it around 1896), Kindai sneaks away from his village, located a three-day walk south of Timbuktu, and, with a few friends, journeys to the sea. They have their first glimpse of white men when they paddle their canoe out to a ship anchored in the bay, and they are welcomed on board. But after an hour or so, the ship draws anchor and begins to move, and Kindai’s friends climb overboard and start paddling in their canoe, only to be capsized by huge waves and devoured by sharks. Kindai, who has been poking around below decks, comes up just in time to witness the catastrophe. As the ship sails away, he becomes terrified and runs amok. Eventually, the ship docks at Glasgow, and Kindai jumps down onto the wharf, where he becomes quite the spectacle. He is rescued by a gentleman who brings him home. Kindai lives for several years with the gentleman, his wife, and their son, who is about Kindai’s age. He learns to speak English and even attends school.

He is given passage back to Africa, to Dahomey (modern Benin). Back with his people, he marries and has children, but he leaves again for reasons he does not explain. They are attacked by murderous Fan people. After being rescued by the black guide for a party of British soldiers, Kindai goes to Quidah and ships back to Scotland. Jews in Glasgow make a fuss over him because he is from one of the Lost Tribes. After another four years, he runs away and travels to England, France, the Netherlands, Germany, and Latvia. In England, he gets his first taste of show business, portraying a West African chief in Coventry’s Lady Godiva parade.

There are several more trips between Europe and Africa, during which Kindai undergoes a series of harrowing adventures. He marries a couple more times in Africa, fathers several more children, and kills a Dahomey warrior in a fight. This man cursed Kindai “with his dying breath,” as Kindai writes many years later, and he believes “that curse followed me even to this day here in New York.”

Not long after he arrives back in Scotland, the man who first rescued him years ago dies, leaving him an inheritance of £1,000. Kindai travels to London, where an astrologer steals his money, and to Liverpool, where he hooks up with a woman who runs a “travelling cinematograph show.” Kindai’s job is to draw customers in by dancing and singing. The show owner also steals from him, but somehow Kindai manages to get passage money across the pond to Philadelphia. There he gets a job in a dime museum, dresses in skin and feathers, dances, and gives talks on Africa. He also discovers he is able to put open flames to his skin without burning himself or even feeling much pain. He calls himself the Fireproof Man and tells his audience that this is a gift he learned from an old medicine man. His act is popular enough for Kindai to graduate to theatres and the vaudeville circuit.

He leaves again for Africa, and in 1911 in Northern Nigeria, he is flogged for not prostrating himself before a white man. He comes down with malaria in Lagos, and when he recovers, he receives passage to England, where he is robbed again. Some Nigerian friends pay for him to go back to America, where he gets stage work because he has brought his “African dress” with him. After a few months he is robbed yet another time and winds up shining shoes in a town in upstate New York, which is where he is when the First World War breaks out.

LoBagola was also an entertainer, and he lectured on Africa and its customs to audiences in Europe and America. The Bookman magazine declared, “Those who have heard LoBagola speak realize that he is a master of the spoken tongue.”

Kindai is assigned to the 38th Royal Fusiliers, a regiment composed mainly of Jews. He serves in Palestine and Egypt. With the war at an end, he is demobbed in England. There he wins the Derby, and then travels to Palestine to teach at a college in Jerusalem. Soon after, in Tanta, Egypt, Kindai converts to Catholicism and teaches at a Coptic school. He eventually goes back to Africa, but he immediately feels lost, so he travels to New York.

He seeks solitude in meditation at the cloisters, but that only lasts a month. Next he is an assistant at Fordham University for one month. He didn’t quit, he “fell into trouble on the streets.” This “trouble” gets him a month in jail.

The whirlwind narrative ends when Kindai, released from jail, works five months in a factory, only to be fired when he asks for a raise. Destitute, he is hired to give a lecture on Africa at a public school in New York. “From that time, I have given many such talks,” he writes.

So ends the record of his life experiences.

Throughout his harrowing story, the author repeatedly refers to the subject of lying. Besides adventure and misfortune, lying is the main theme of the autobiography (victimization being a subtheme). As a teenager in Scotland, Kindai remembers, “I was on my way to being civilized, but I was not quite civilized enough to tell lies.” And later, “I didn’t know how to lie until I met white people … Here is where the science of a good lie saved me a lot of trouble.” But just a turn of the page from that last statement, in the recounting of a folk tale, the author has a wise old elephant declare that “a lie is never justified.”

Well, Bata Kindai Amgoza ibn LoBagola was really Joseph Howard Lee, or so he claimed in 1934 when he was about to be deported to his supposed birthplace of Dahomey. He insisted he was born in 1887 at 620 Raberg Street in Baltimore, Maryland, the 17th child of Joseph, a cook, and Lucy, a domestic servant.

In repudiating the story of his life to his interrogators as given in his autobiography published four years earlier, “Mr. Lee” told what he called “the real truth,” a story that, although unverifiable, was accepted. This one was filled with derring-do of another sort, the adventures of a merchant seaman roaming the seven seas and doing battle with injustice.

Actually, he was a street character who probably started out on one of those corners made notorious in recent years by the HBO television series The Wire. Besides being a corner boy, “Joe Howard Lee” was a male hustler. It is true that he was a merchant seaman and that he did see much of the world, including Africa. He was also an entertainer, and he lectured on Africa and its customs to audiences in Europe and America. He also appeared at several American universities, where he was taken seriously. His ability to con even African experts is indicated by his experience in 1911 at the University of Pennsylvania Museum, where he lectured on African language and culture. His sponsor was Frank G. Speck, assistant curator of general ethnology at the museum and later the founder of the anthropology department at the university. Speck spoke with LoBagola at length and recorded him on wax cylinders singing “authentic songs of his people.” His talks drew large crowds and garnered good press notices. The Bookman magazine declared, “Those who have heard LoBagola speak realize that he is a master of the spoken tongue.” Another magazine described him as “one of the greatest of platform entertainers.”

The only traces remaining of this mysterious individual’s life are found in a few letters exchanged with a booking agent, some folders that attest to various vaudeville bookings, and records from various prisons where he was incarcerated, usually for “sodomy” and “perversion”, for a total of 13 years. One of the problems with his business correspondence is that many of the letters bear a salutation to someone who is not Kindai, nor Joe, Joseph, Howard, or Lee. There is a “Dear Luke,” for instance, and just a plain “Reese”. One contract is signed “Alvin Johnson”.

As for the origin of his African name, he probably cobbled it together from those of different African performers on European stages, such as Angazza Bogolo, Beah Kindah, and Peter Lobengula.

But all these “proofs” are of the existence of someone calling himself Bata Kindai Amgoza ibn LoBagola. The certificate of naturalization he handed over to authorities was, of course, a fake. The birth certificate was genuine, but was it his? At the line where the name of the child was to be entered, the notation is “unnamed seventeenth child.”

There is a trickster/hustler figure who shows up in Black American song and story and folk tale. The man calling himself Bata Kindai is one of these, only to an extreme.

But who he really was, nobody knows.

The remains of whomever he may have been occupy Plot 29 in the graveyard at Attica—now the Attica Correctional Facility in New York.

But his assumed name lives on amongst the lore of investors. In his book, he tells the story of an elephant stampede. The beasts rush through an area and always return the same way. When there is a surge of the market that soon ceases and comes back again down that same path, that’s called a LoBagola.

As for that man named LoBagola, one doubts that his like will ever come back down the pike again.

Photo provided by the Penn Museum.