Painter Barry Oretsky

Precision of craft.

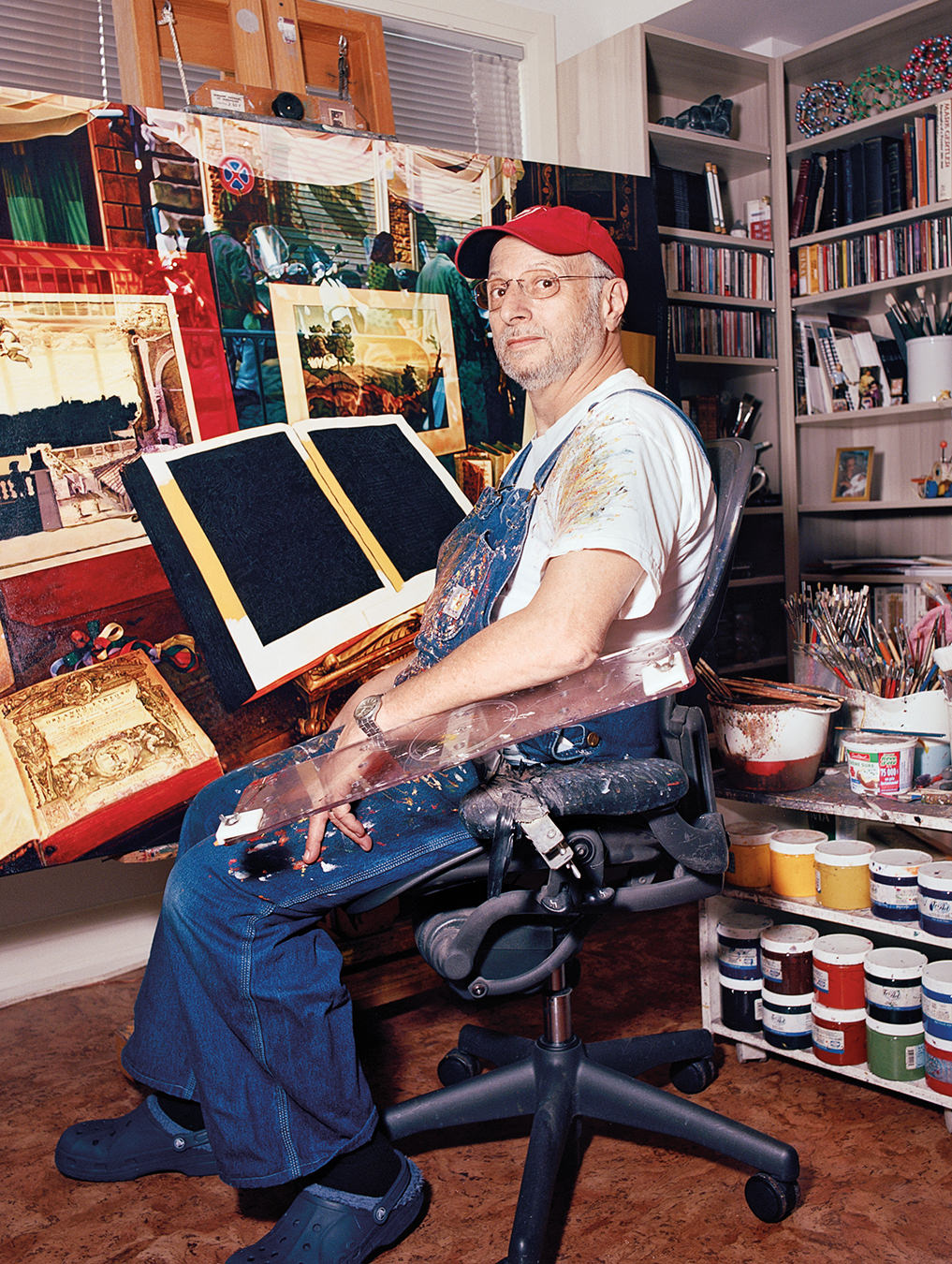

Painter Barry Oretsky is a matter-of-fact man, and he is not. At his Toronto studio, where he hunkers over a massive canvas, there is something both plain-spoken and mystical going on as he describes a small portion of his technique.

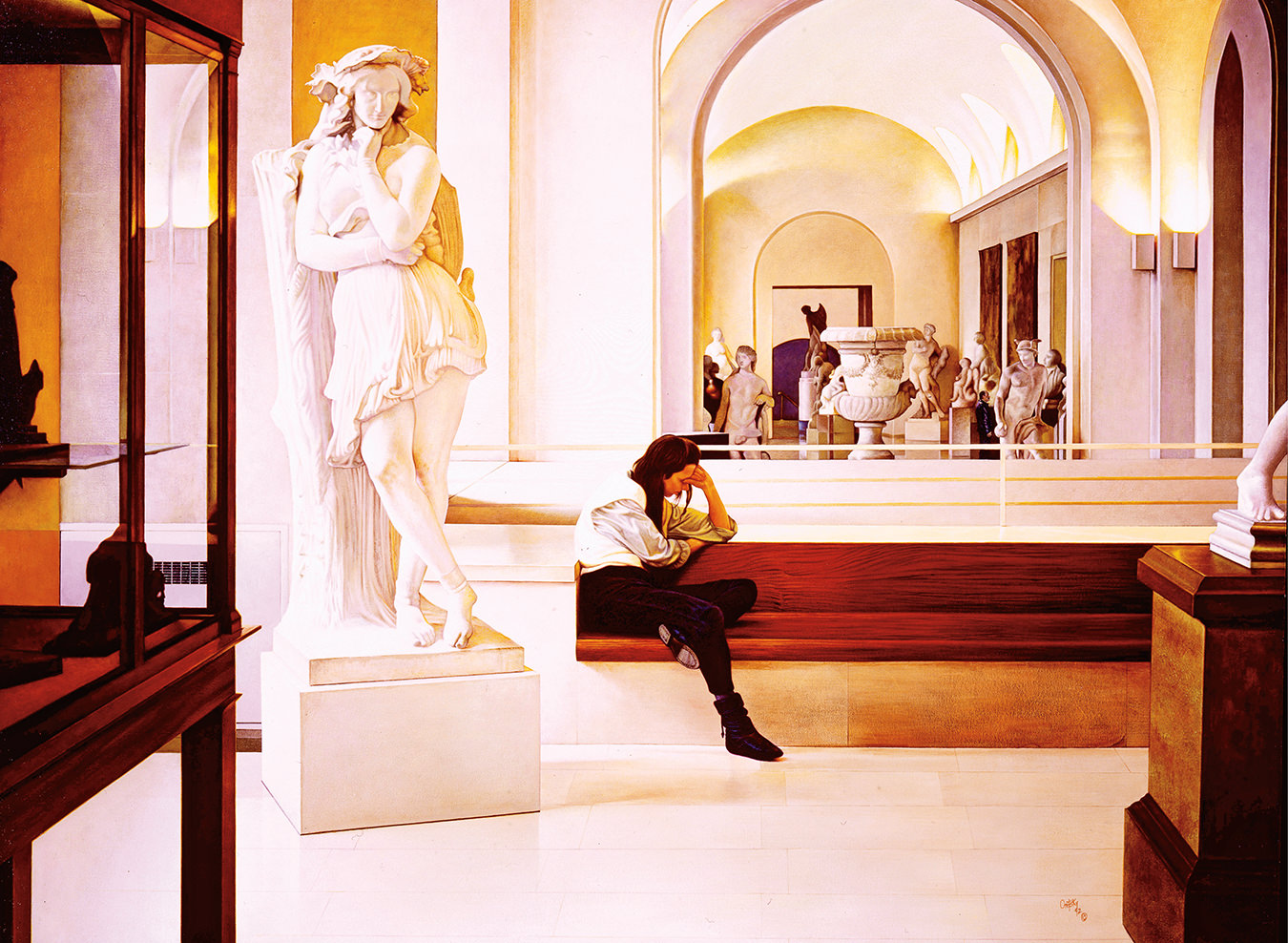

The work depicts a bookshop’s display window in Rome. Through the glass, at the centre of the display, we see an open book, anchoring the image. It is surrounded by other books and artworks, like some allegorical painting representing the different schools of philosophy. In the window’s glass, shimmering apparitions appear, reflections of pedestrians over the viewer’s shoulder. (“I am enamoured of reflections,” he tells me; indeed, they appear in a majority of his current works.) In the corner of the canvas, if you look just so, you can see Oretsky himself with a raised camera, a shadow in the glass.

The book at the image’s centre will soon be brought to life as an illuminated copy of St. Paul’s Epistle. But today it is a space painted black. This is one of the intricacies of Oretsky’s technique; while everyone else paints on white canvases, his starting point is a dark base with a muted white line drawing, a blueprint for what’s to come: from here, he builds up many layers of colour. “Let me show you something here.” He mixes a dab of mossy green on his palette, and applies it to a white piece of paper and then to the black square on the canvas. Holding the paper up to the canvas, he asks, “Are these the same?” And, to my surprise, they’re clearly not. All perception of colour is, of course, achieved by the reception of light bouncing off surfaces. Oretsky insists on black surfaces so that the light will bounce off nothing but the paint he’s working with.

“The human eye takes in the fastest wavelength first,” he explains. “So when you put a colour on a white canvas, you see the white first. You physically can’t see the colour you’re supposed to be working with.” It’s a conclusion that Leonardo da Vinci reportedly arrived at as well.

Even the lighting in Oretsky’s studio is guarded. Five halogens spot the ceiling, though they aren’t permitted to stare directly at the canvas. Oretsky wears a baseball cap as he works, and he shuts the blinds too, for fear that excess light will wash things out and blind him from the truth.

There’s a care in this work that by sheer volume of commitment demands respect. The canvas we’re sitting down with has taken 18 months of labour so far. There are another four months to go.

As I sit before his canvas, he gets up and switches off the studio’s lights. “You see this?” he says, excitedly. “See this?” Oretsky points at the canvas, which appears to shimmer. “This is not a mirage. The canvas has its own light. This is constructed light, made of the Earth. That is what painting is about.”

I’m interested in Oretsky’s technique in particular because the man is one of the great realist painters on the continent. He has little time for the purely conceptual, and while observing his masterful style, it’s hard not to be reminded that ultimate precision of craft is too rare a thing among today’s painters. One is reminded of the art school students, sure of their talents, who are flummoxed when asked to draw a true circle.

There’s a care in this work that by sheer volume of commitment demands respect. The canvas we’re sitting down with has taken 18 months of labour so far. There are another four months to go.

This is when I make the mistake of calling Oretsky a photorealist.

“I hate that term. Photorealist.” He almost spits the word. I meant it as a compliment, though, because I’m fond of any painter who commits to the actual depiction of lived reality in a world where most painters seem to shun that ambition. The advent of photography as a legitimated art form caused a small crisis in the painting world; some said photography “took over” the job of representation since photos were perceived to be so unswervingly exact. But, for Oretsky, the term is clearly fraught.

“Photorealists take a given image and then give it their slavish attention,” he says. “They want you to walk in and be fooled, to walk in and go, ‘Oh, there’s a giant photograph.’ It’s really meant as an illustration of your gifts. It’s a technical feat. It’s not about conveying narrative with any depth or meaning. But to me, the initial image is a jumping-off point—it’s data from which I can reconstruct in my own language.”

This is the strange paradox of Oretsky’s brand of realism. On the one hand, he refuses to stage a scene before he takes the photograph that he’ll later reference: “My own ego is a little different from someone like Jeff Wall, say. I think the good Lord provides me with all the images I could want. And then my job is to act as a conduit—to disseminate that vision to a greater audience.” But at the same time, he will actually use about 30 different detail photographs (of one image) in his creation of a single painting. “This is how I can create my own light,” he explains. If Oretsky were to simply reconstruct what a single photo showed him, the result would appear flat and cool by comparison. In an Oretsky canvas, to borrow the Foer title, everything is illuminated. “I light the image according to my own vision of what something looked like—my own lived experience.”

Control of light is something Oretsky has learned from his masters. His idol is Velázquez. Back in 1970, Oretsky saw the Spanish painter’s Portrait of Juan de Pareja for the first time at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. It’s a portrait of the master’s assistant, his slave, in fact, whom Velázquez eventually set free. “They don’t call that painting a painting. They call it truth,” says Oretsky. “Every time I go to New York, I visit the museum and sit in front of that painting for 20 minutes to pay my respects. This is liquid light that he’s working with.”

And then there’s Rembrandt, naturally. “You know how he got that lighting in his portraits? He cut a tiny hole in his ceiling so light would pour down just so. You have to control the light, or it will control you.”

We’re looking over the canvas some more and I start thinking out loud about this idea of control. I observe that the painting, despite its undeniable beauty, never feels quite settled. There’s a slight static; the vantage is ajar; the lighting (though managed to the nth degree) is unreal, or super-real.

“No, you must never make it saccharine. It must never be too perfect,” he says. “I never want to make some sugar-coated denial. The grass goes up and the grass goes down, you know?”

The position is a realistic one, and it’s also one Oretsky comes by honestly. He served three years in the Israeli military, though the man whose eye misses nothing doesn’t want to give me any details about what he saw during those years. “I saw some horrible things. Some people didn’t make it through, but I did. So you see, I’m not allowed to rest. I’m not allowed to rest with the time I’ve been given.”

In an Oretsky canvas, to borrow the Foer title, everything is illuminated. “I light the image according to my own vision of what something looked like—my own lived experience.”

Barry Oretsky was born in Owen Sound, Ontario, where his family was in the fur business (there’s still an Oretsky Fur Company there). The place has punch above its weight class as far as producing Canadian culture makers goes: besides Oretsky, Owen Sound is birthplace to Billy Bishop and also Group of Seven painter Tom Thomson. As a child, Oretsky would go to the town library on Saturdays and watch National Film Board flicks about the Group of Seven. “Tom Thomson was my be-all and end-all back then.”

Art school was Central Technical School in Toronto, where he trained to be a commercial artist, thinking that would be the only way to feed himself. He learned to use graphic tools that are still incorporated in his process, tools that kids in art school today wouldn’t know how to work with. There, he met Doris McCarthy, an instructor and a contemporary of Lawren Harris. Oretsky was 14 when McCarthy handed him a book that she hoped would help explain this art world he was so desperate to be a part of: The Agony and the Ecstasy, an in-depth biographical novel by Irving Stone about Michelangelo. “It explained to me the commitment that you have to have in order to be a painter,” says Oretsky. “You know, I made every person in my family read that book. I’ve carried it around with me ever since.”

The talent—both inherent and earned—in the young Oretsky was obvious. He was top of his class each year. After school (which included Central Saint Martins College of Art and Design in London), there were years of work in advertising and as an art teacher while he honed his craft and built his reputation. A major solo show at the Bau-Xi Gallery in Toronto in 1986 ought to have been his breakthrough moment. But whether because of the fickleness of the art market or the vagaries of Canadian economics, not a single canvas sold. Frustration was short-lived, though. Three years later, the same work that would not sell for $5,000 in Toronto sold for $25,000 in New York. “It was unbelievable,” says Oretsky. “I was in The New York Times, Art in America, everywhere. And everything changed.” The two decades since then have been kind indeed. Oretsky’s work, while still painstaking, enjoys global acclaim. However, the man who doesn’t want to be called a photorealist doesn’t want to be called an artist, either. Or at least he won’t call himself that. “I’m a painter. Just a painter. If the work I do hits the level of art, then that’s for others to say.”

Painting—or Oretsky’s kind of painting, anyway—is serious, backbreaking labour. Now, 66, he admits, “I won’t be able to keep this up forever, no.” Perhaps the real problem lies in our love for the evidence of Oretsky’s labour. It’s so easy to value his paintings based on the 18-plus months of passionate consideration evident in those miniscule strokes on the canvas, even when we should be appraising them for their vision, the totality of their vision, instead. Besides which, Oretsky’s work (for all its precision) is never perfect. “I try to invest my paintings with humanism,” he says. He slumps a little, happily, in his chair. His hand rubs absentmindedly at the left shoulder of his T-shirt, which is coated with a mess of colours where he habitually wipes his brush.

Photos of Barry Oretsky’s paintings by Michael Moore, See Spot Run, Colourgenics, WFO Mixed Media Inc.