Dreaming Big In Kathmandu

Goats and tigers.

At one end of the sprawling temple complex known as Kathmandu Durbar Square there’s an open plaza where merchants spread their handicrafts on the ground. Just before you make it past the last beckoning call, you will pass a final blanket. It belongs to the Rai family. Some days, 15-year-old Sharmila Rai shows up to help her father, Surendra, hawk curios to tourists. I was determined to reach those temples, but she snared me. Her open smile and sincere enthusiasm would not be denied. The temples would have to wait.

Soon I was sitting on a little three-legged stool, listening. Sharmila attends Jubilant Higher Secondary School in Kathmandu. She comes here to help the family business, but she’d rather be in school all the time. “Education is the most important thing to me,” Sharmila tells me. She’s a great salesperson, and her best pitch is for her own future.

“I have big aims,” she says, perched beside me in the sunny square. “I will become a doctor. Then I will go back to the mountains and help people for free. Many girls do not get an education. They have babies when they are still young. But I will get an education. I want to go away to school. I want to go to university in a foreign country. Then I will come home and help people.” She looks at me with a smile that most kids would save for Disneyland. “You are my first foreign friend,” she says. “Thank you for talking to me. It is a happy day for me to meet you.”

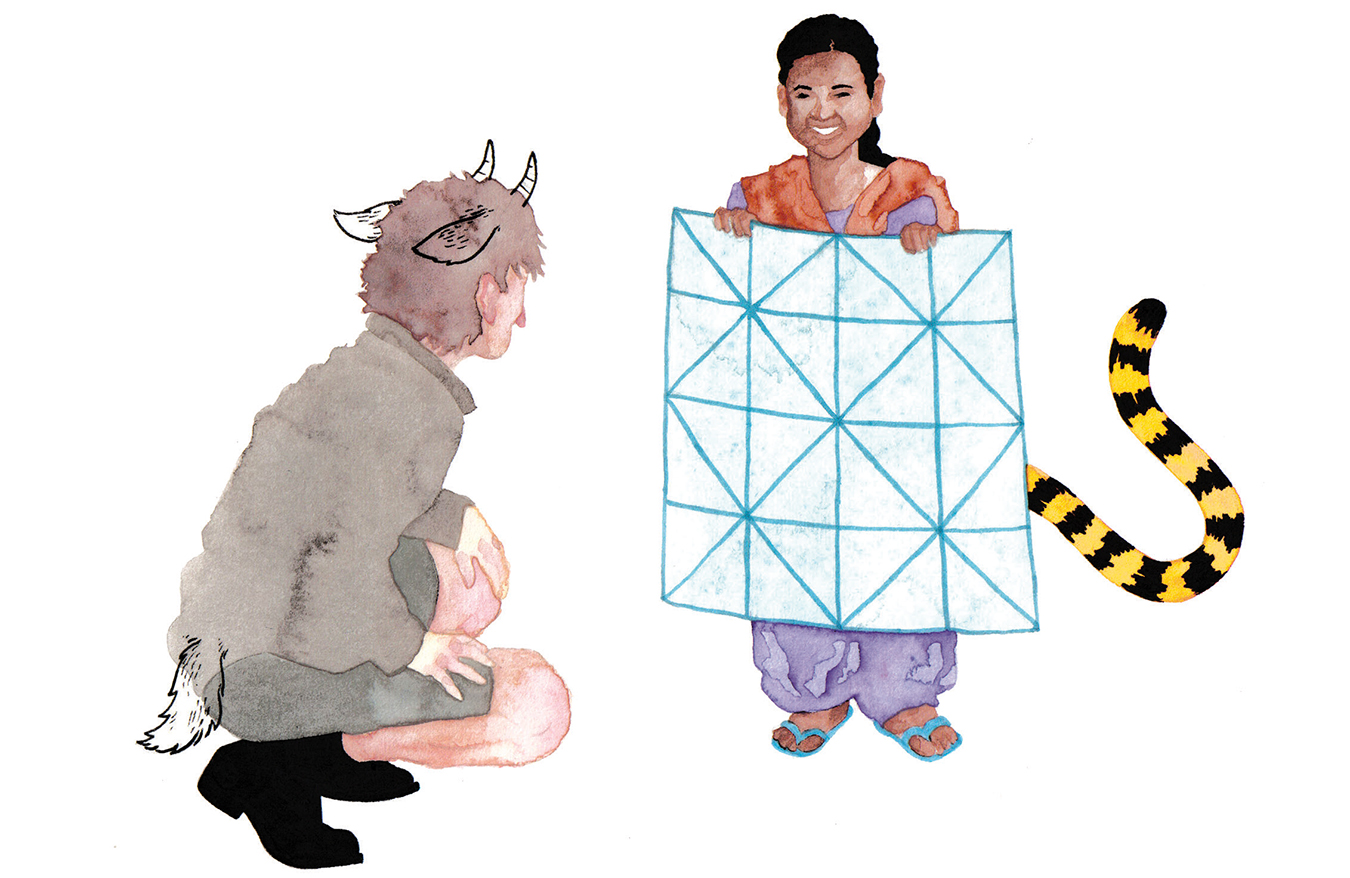

There are plenty of items for sale on the family blanket, but Sharmila does not seem particularly intent on selling any of them, at least not directly. Nonetheless, my eye falls on one offering—a wooden board with a red metal plate on top, criss-crossed with a grid of lines. In the corners of the grid stand four little brass tigers.

“This is a traditional Nepalese game, tigers and goats,” Sharmila says. She brings out a handful of little brass goats and places a few at intersecting points on the grid, explaining what turns out to be a sort of ruthless variation on Chinese checkers. One player gets the goats, which are placed on grid points one at a time. The tigers move in for the kill step by step—jump a goat and you’ve eaten it. It seems rather one-sided. But with clever placement the goats can trap the tigers, which require an open space to make a jump. Crowd all four tigers into immobility and the goats become the improbable victors. “But it’s easier to be a tiger,” Sharmila agrees.

I buy one. Sharmila is determined that this will not be the end of our relationship. “Please come back and visit me again,” she pleads. “You can come to our home for dinner.”

Just beyond the Rai’s open-air retail operation lies the chaotic heart of riotous Kathmandu. Some of the city’s holiest temples are here in Durbar Square, surrounded by cattle and shit, vendors and garbage, and vehicles of all descriptions coming at you from every point on the compass. There’s a goddess too—a live one. She is the Royal Kumari, and she is four years old. The Living Goddess Kumari occupies a temple with a quiet courtyard where she makes random appearances to the public. Each new Living Goddess Kumari is selected based on 32 qualities—some physical, like black hair and good teeth, with others including a calm demeanour, a cow’s eyes, and a lion’s heart. Little candidates are placed in a dark little room and subjected to random terrors, like a midway haunted house ride. The successful candidate will come through this experience with a clean nappy. Once selected, the new Kumari hangs on to the role until the onset of menstruation. Then they find a new goddess. Presumably the old one goes off to leave a resumé at Pizza Hut. A washed-up goddess at age 12—surely the Olsen twins would understand.

Hey, it’s a gig. They are not easy to come by for young Nepalese girls. Sharmila wants to be a doctor. For that, a cow’s eyes will get you nowhere. But the heart of a jungle cat? Always handy. Sharmila has it covered.

My final day in Kathmandu is approaching. I return to Durbar Square late on a Sunday afternoon. Surendra spots me from halfway across the square, as if he has been waiting for me since my first visit. “Sharmila is not here—she is at home,” her father tells me. “She will be very happy to see you.”

When Sharmila started attending her English-language school, times were better for the Rai family. Tuition is expensive. “Forty thousand rupees a year,” he says (about $560 Canadian). “Sharmila has big aims, but they are expensive,” says Surendra. Plus there are three other girls and a four-year-old son to consider. “She wants to go to university in a foreign country. But this is for rich people.”

Sharmila dreams of being a tiger. It’s an admirable goal. But getting a shot at earning those stripes is tough when your family, more often than not, has to play the role of the goats.

We set out for the Rai home, but before we get halfway through Durbar Square, Sharmila intercepts us. She is overjoyed. Taking me by the hand, she leads me to a long, narrow laneway made of equal parts bricks and dirt, sloping down to create a little urban valley between closely packed apartment blocks, rising up again on the far side. Near the bottom, we turn off into a still-narrower alley populated by a few children and stray dogs. Inside a ramshackle apartment building, we step through a hanging blanket into a single room. Sharmila calls to her mother in a kitchen somewhere down the hall—there’s a visitor for dinner.

The room is painted green and smells vaguely damp. There’s a couch, a cabinet full of pictures and books, and a large daybed piled high with blankets. Sharmila’s four-year-old brother and a neighbour’s boy play on the couch. Sharmila introduces her sister Mila. Somewhere in the pile of blankets is her two-month-old son, Levi.

Sharmila is clearly hell-bent on achieving her goals and it’s a wonderful thing to see. But tigers need goats. I wonder if I’m being fitted for a pair of horns.

“When things got harder for our family,” Sharmila explains quietly, “she decided that she should help out by going away so that my dad would not have to look after her. She had a boyfriend and then she had a baby. But he is not around now—he was no good. My dad took her back in with the baby. Now the neighbours say this and say that. Nepal is not like Canada. She cannot go out and find another man. Everyone talks.”

Sharmila fetches a brochure from the bookcase and sits down beside me. The brochure describes a media studies course she is eager to take. But it’s expensive, and as it is, the schoolmaster is nagging Sharmila’s dad for payment of back fees.

I’m uncomfortable. I wish it wasn’t so, but I can’t deny it—I am squirming. Sharmila is clearly hell-bent on achieving her goals and it’s a wonderful thing to see. But tigers need goats. I wonder if I’m being fitted for a pair of horns.

There can be no doubt about Sharmila’s sincere desire for education. But the suddenness of her affection has made me nervous. “The day I met you is my lucky day,” she says. “You are my first friend from a foreign country. You are in my heart forever.”

Am I really that charming?

The February 10, 2009, edition of the International Herald Tribune contained an interesting letter from Lawrence Bohme of Saint Jean de Luz, France. He described a visit to an Ethiopian town where children have developed an interesting routine for tourists: “Boys accost them, not asking for money, but for one of several schoolbooks displayed in a nearby shop window. Could the kind visitor buy this geography or history textbook for the child’s schoolwork, since his own parents are unable to? Quite a few tourists … buy the book and place it in the boy’s hands. Later, of course, the boy returns the unopened book to the conniving store-keeper who splits the profit with him.”

It will soon be dark. In Kathmandu, that means something. To say the city suffers power outages would be misleading—better to say that sometimes the power comes back on. Dinner is not yet ready, but I make my apologies. I should start back while some light remains.

Sharmila and her dad escort me back down the narrow, rutted lane and on toward Durbar Square. “You have a Nepalese family now,” Sharmila assures me. At the door of the apartment I had given her a 1,000-rupee note (about $15 Canadian), agonizing over the amount like a yokel in a fancy restaurant trying to figure the appropriate tip. I watched Sharmila’s face for signs of disappointment—15 bucks won’t pay for much tuition—but perceived none. Leading back to the square, she seems as warm and enthusiastic as ever. “Send me e-mails, don’t forget,” she says. “I hope I will see you again.”

I slip into the evening crowd, walking along past open fires, heading back toward the Thamel district. There is a knot in my gut. What was that all about? Was Sharmila simply a seeker after friendship and the broadened horizons it can bring? Or was she playing me?

And does it matter? By Canadian standards my income is modest. By Nepalese standards I’m a rich man, and Sharmila knows it. I wouldn’t be buying a plane ticket to Kathmandu otherwise. If Sharmila was playing me, at least it was for a good cause. She has, as she says, big aims. And when a target approaches, I suspect her aim is excellent.

Sharmila sends e-mails. She talks of school and says she misses me. One early e-mail mentions financial trouble—a bit of foreshadowing, I am sure. Finally the shoe drops:

my dear steve namaste!!!!!!!!!!!!! how are you? here i finished my exam already. i did very well on my exam. now after few week i will be in grade 10 but i am not sure i can go to same school or not. my father bussiness is not enough to send me the school… i have a big aim in my life i want to success it… so please if you can help me this year. i have only one more year left to finished my school. i am very apolized to say you this. but i don’t want to break my dream too. you know my father have a just small street shop it is very difficult for my father to support all family… my family send you big namaste and they bow down their head for you in respect…

I’m writing about Sharmila. And being paid to do it. I can’t support her on an ongoing basis. But I can send her a cheque. She deserves that. Happy hunting, young lady. May all your goats be plump and slow.