Yann Martel

Life of Yann.

“For four years, my office was a lifeboat,” says Yann Martel in a melodic, perfectly articulated voice. “And in it, there was a tiger.”

Martel is referring to the time he spent working on his novel Life of Pi, which was nominated for a Governor General’s Award for fiction in 2001, and which won the Man Booker Prize, one of the most prestigious fiction prizes in the world, in 2002. Since its inception in 1969, only two other Canadians have won the Booker: Margaret Atwood and Michael Ondaatje. In addition to the Booker, the novel won a plethora of other literary awards and nominations. Pi has since been translated into 40 languages and has sold more than 6 million copies.

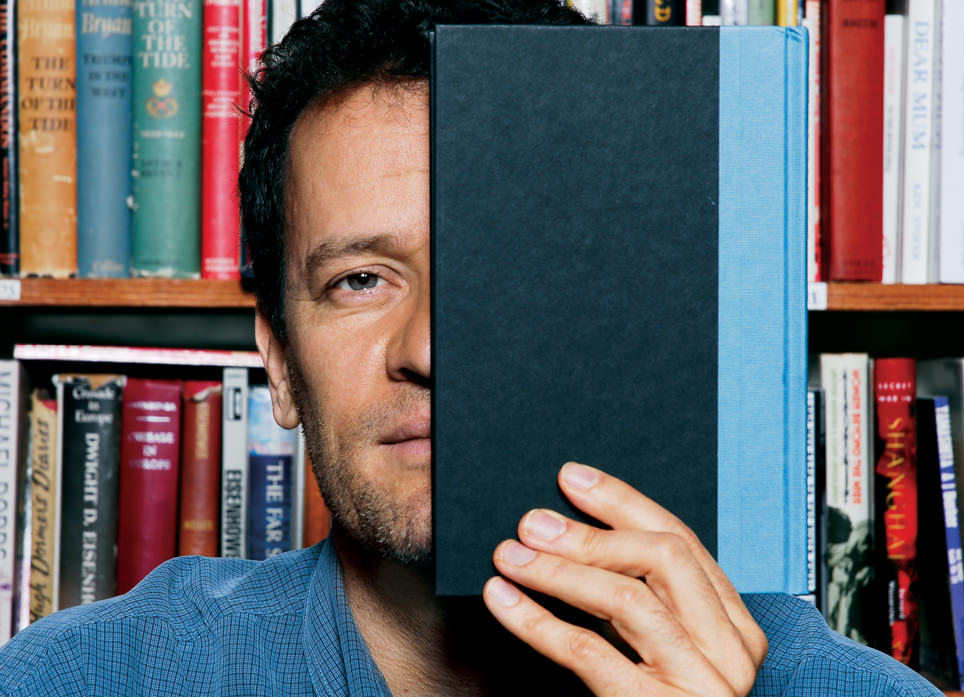

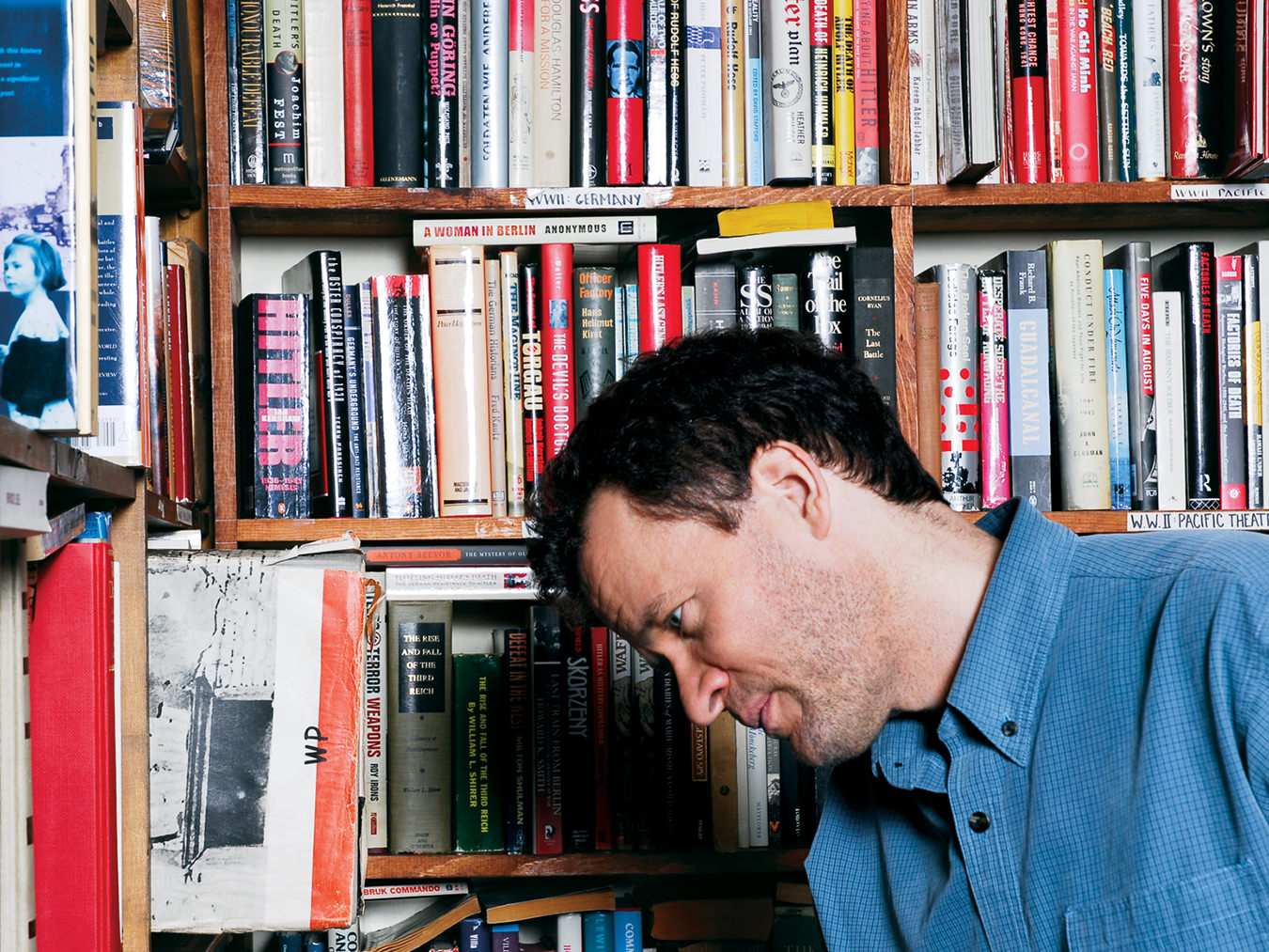

The book is about a lifeboat that contains a boy named Pi, a hyena, a zebra, an orangutan and a 450-pound Royal Bengal tiger, and is bobbing in the Pacific after the sinking of a cargo ship. I meet Martel at Vancouver’s Shebeen Whiskey House on a rainy morning, and when I listen to the recording of our conversation later, strangely, eerily, it sounds as though we’re in the steerage class of a ship, pitching and rolling in a storm. It is actually the sound of the rain; the echo of the empty room with its brick walls, wooden floors and high ceiling; the whir of a fan; and the intermittent noise from the construction work going on outside. Martel fits in well at Shebeen, where literary events have often been held over the years. He’s just come from MacLeod’s Books, another Vancouver literary landmark, where he was photographed amongst stacks of dusty volumes in the military history section.

Leaning back in his chair, he begins our conversation by singing a chorus of praise to the city of Saskatoon, where he currently lives. “It’s the people and the landscape. The rivers are beautiful, and I like the undulating flatness. It’s a good community. You can connect with people, it’s easy to get around, and you don’t have all the ills that come with big cities. I love it,” he says. “I wouldn’t be there if I didn’t.”

Martel’s parents were Canadian diplomats. He was born in Spain and grew up there, as well as in Paris and Central America. He attended university in Ontario, and later moved to Montreal, where his parents now live. “As a little kid, I read a lot,” he says, “and I loved that, because it was an adventure. But I’m not one of these people who at age 12 was determined to be a writer. I’m not particularly prolific. I’m 44, and I’ve been doing it full-time roughly since the age of 27, and I’ve nearly finished my next book. So four books, that’s 17 years—and they’re not particularly long books.” Prior to Life of Pi, Martel also published a collection of short stories called The Facts Behind the Helsinki Roccamatios, and the novel Self, a fictional biography of a young writer and traveller who awakes to find his gender has changed overnight.

He continues, “In university, in second year, I wrote a really bad play. I knew nothing, but I enjoyed writing it. There was something so pleasurable to have a stage and put people on it and make my point on the world. I never found anything that I liked more than that, so I kept at it. I wrote another play, then short stories, and bit by bit, I got better. Practice makes better. I was waiting for life to start and doing this on the side. I got lucky. The Malahat Review published my first short story. A friend had sent it in without telling me. The first I heard was the letter of acceptance and the promise of $125, which I was amazed at. I wrote another one right after. Then I sent 16 stories to 16 magazines and got 16 refusals, so I said, ‘Okay, that’s reality,’ and I kept writing.” Eventually, he won the Journey Prize and got an agent, and was on his literary way.

“Everyone dreams of fame and fortune as a writer, but it doesn’t happen very often, and that’s not why you write. I thought Life of Pi was a deeply unfashionable book – religion, defending zoos – and therefore it wouldn’t have the success that it had.”

Martel says his parents helped make his writing career possible. “I had my own little Canada Council for the Arts.” His father, Émile Martel, won the Governor General’s Award for French-language poetry for Pour orchestre et poète seul. “They’re good parents, they respect the arts and they just want me to be happy. They’re very supportive, not skeptical. My mother—as mothers typically do—thought my first play, which was dismal, was brilliant. You need that initial support, and you need it at the level of a society too. In a sense, the Canada Council is a mother who encourages all her children, saying they’re all excellent. Time will prove the ones that are and the ones that aren’t, but if there was no Canada Council, there’s no nursing mother. We’d have no artists—we’d be a branch plant of the United States in terms of our culture.”

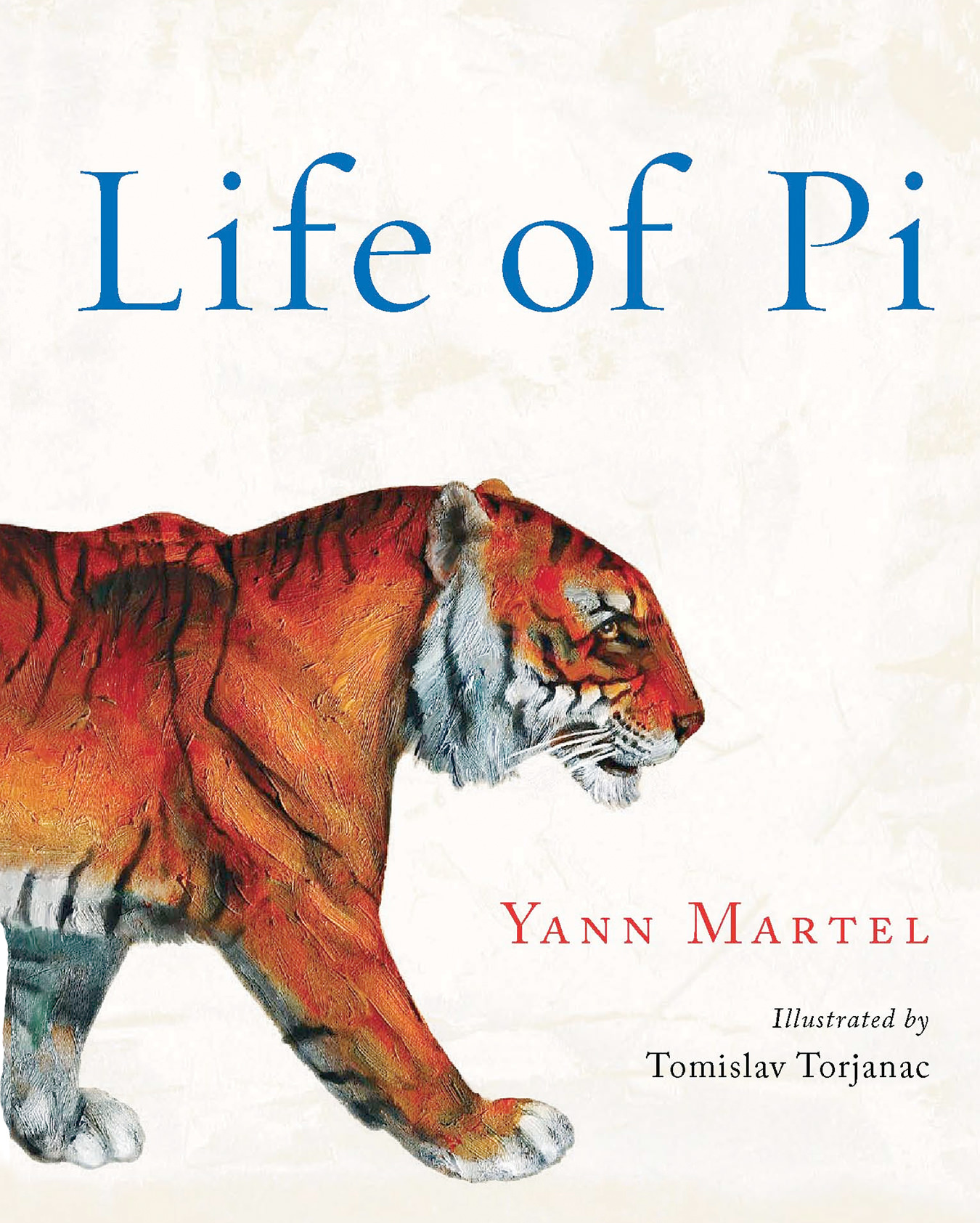

We discuss Life of Pi, a new edition of which has recently come out, illustrated by Tomislav Torjanac. “My dream was that a small number of people would diligently like it,” he says of his novel. Martel says he knew Pi was a good book while he was writing it. “I was hoping that it would be a cult classic. Everyone dreams of fame and fortune as a writer, but it doesn’t happen very often, and that’s not why you write. I thought it was a deeply unfashionable book—religion, defending zoos, combining the two—and therefore it wouldn’t have the success that it had. I’ve been incredibly happy that it has.”

He says he didn’t set out to write a story about animals and religion. “I was interested in exploring faith, and in a secondary way in exploring animals, though that was really just to serve the story.”

Martel finished writing Life of Pi while he was living in Montreal. “I would get up in the morning, exercise and write. It was quite a simple life of the mind. There is a great simplicity to being a writer who just writes. After the success of a book, you need an accountant, you get more e-mails, more invitations. The world intrudes on you. I’m not going to complain about that, but your time becomes precious, whereas before some of your time was infinite.”

Life changed dramatically for Martel after the Booker. “Life after the Booker went whoosh!” he says, gesturing with his hand. “I had invitations to everywhere. I stopped writing for a year and a half. When I won, I was teaching a course at the Free University of Berlin. I literally travelled every single weekend. When the term ended, I did all sorts of trips and festivals and launches. If you get an all-expenses-paid trip to Hong Kong and are put up in a fabulously luxurious hotel, why would you not do that? It was fun, and gratifying too—I was travelling to meet publishers, readers and festival organizers. But after a while, you want to get back to a sane life.”

He is currently a visiting scholar at the University of Saskatchewan—“which means I’m working on my [new] book. I have a small office on the third floor of the library in the literature section, with a big window and a nice view of campus. It’s quiet. There’s no phone. I love it.” The new book includes a novel and an essay, both on the Holocaust, both with the same title, back to back and upside down, in flip-book format. “It’s not meant to be gimmicky. My concern is how do I best present these two wares—fiction and non-fiction, which are held to be incompatible? The essay is very much an extended act of reasoning, discussing facts and books. The novel is clearly fictitious, an extended dialogue between a red howler monkey and a donkey, living on a shirt that’s also a country.”

For the past year, Martel has also been working on another project: every two weeks, he sends a book to Prime Minister Stephen Harper, along with an accompanying letter discussing the book’s merits. He documents the exercise on the website www.whatisstephenharperreading.ca. “I’m doing it to make a point,” he says. “Books are one of the key ways to understand life. We’re allowed to ask politicians questions because they are accountable to us. If we’re allowed to ask them about their ethics and finances, then why not their imaginations? Why can’t we ask, ‘Mr. Harper, have you read anything by a Russian writer? Have you read anything by a Canadian writer?’ We expect our politicians to have a minimal knowledge of the geography, history and economics of Canada, so isn’t it fair to expect them to know a bit about Canadian culture?

“It goes beyond Canada to me. The whole West is led by middle-class men who, broadly speaking, don’t question themselves in artistic ways. They’re deluded by the busyness of politics and of business. You never hear politicians say, ‘What could increase the quality of life here? Should we work less?’ Can you imagine a politician saying that it doesn’t matter if we’re not making more money, what we want to do is redistribute it better?”

Thus far, Martel has only received a single reply from the Prime Minister’s office, which is posted on the website (it was in response to the first book sent, The Death of Ivan Ilych by Leo Tolstoy), but he hasn’t been dissuaded. “What makes a good life has very little to do with economics, beyond the minimum level of comfort you require. It’s all up to you—how you interpret your life, the relations you make, how you enjoy them, what you do with your time. My experience as a writer is that there’s nothing more satisfying than a life of the mind. It doesn’t mean you’re not exercising, or just sitting there cogitating. It means living a life of curiosity. Enjoying sentences, splashes of paint, riffs of music—that is what makes people happy.”

Things are in place for a movie based on Pi, to be produced by Fox 2000, a division of 20th Century Fox. “The director Jean-Pierre Jeunet, the man who did Amélie, has co-written a great screenplay and the studio is passionately behind it. We’re going to film it in Spain, but the American dollar is so weak in relation to the euro that it’s making the movie more expensive for the American studio—and it’s an incredibly expensive movie to shoot because of the tiger and the water. We’re hoping that in the next year or so they’ll find a cheaper way of making it, or the American dollar will pick up.”

He says it isn’t hard to let someone reinterpret his work. “I’m not a screenwriter. I’d rather trust someone who knows how to make movies to write it. I’m really happy with Jeunet. I think he’s a talented filmmaker. I told him to take liberties. Movies that are too faithfully based on books tend to be stilted, especially the dialogue—they feel literary, and literary doesn’t work with movies.”

The next evening, Martel speaks at the University of British Columbia. Someone in the audience asks about a section in Pi referred to as “the island”. “The island,” he answers, “was part of my overall narrative strategy. One story had to be hard to believe, and the other horrifically repelling. I hoped the island was the snapping point for the reader. I wanted the first story to require a leap of faith. We live in a world of technology where the world of art suffers. Life presents you with a set of facts you don’t get to choose, but you can interpret those facts. I ask of the reader—just as Pi asked—in your own life, which is the better story? To me, the transcendental story adds a layer of depth and potentially greater meaning.” At the end of the night, Martel signs a copy of the new illustrated edition of his book for a young woman. The inscription reads, “May your lifeboat overcome every storm.”