-

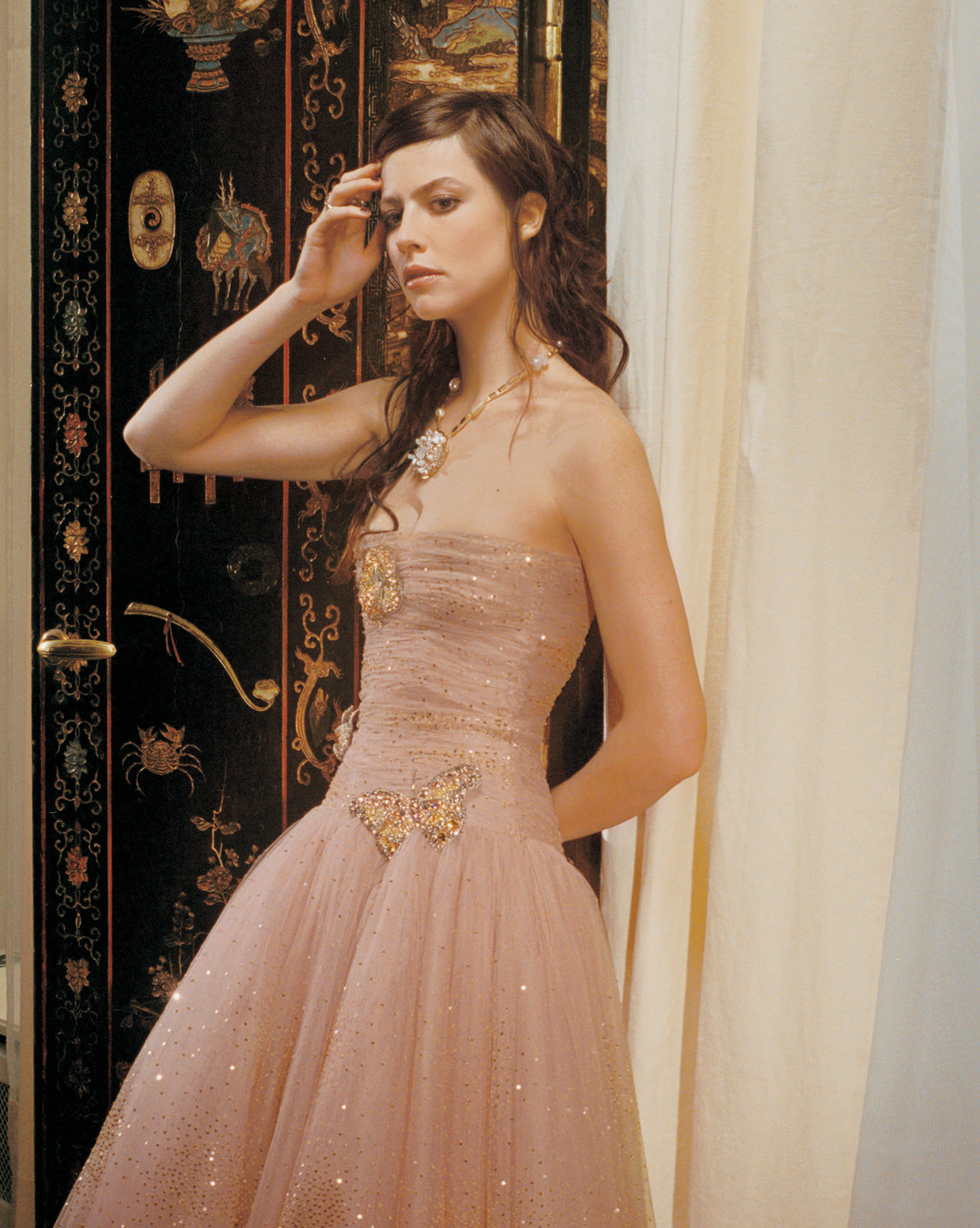

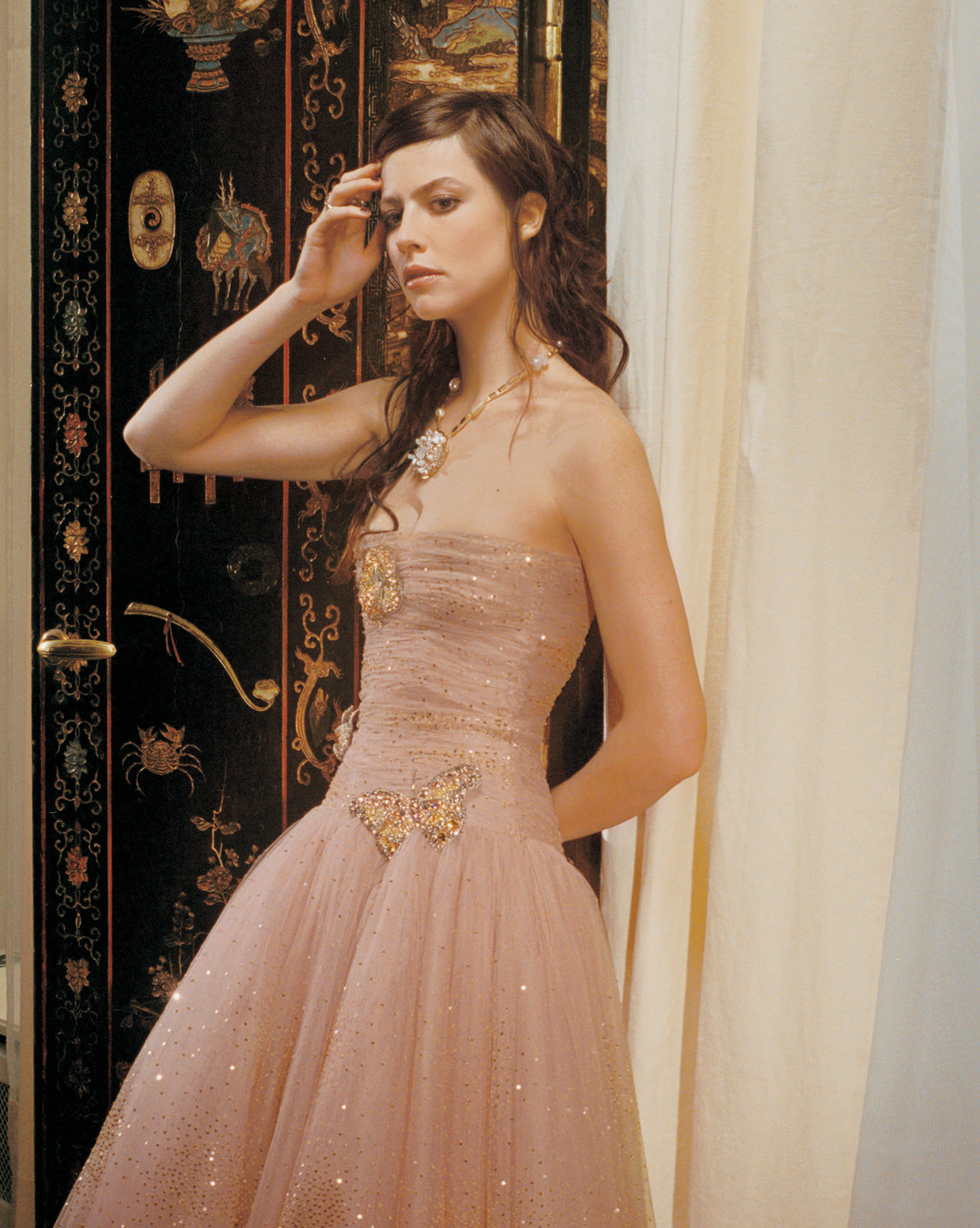

Dress from the Chanel Haute Couture Collection spring/summer 2003. Ring on index finger Comète 2002 en deux parties from the Chanel Fine Jewellery Collection.

-

-

Pettycoat and ballerina tulle skirt from the Chanel Haute Couture Collection spring/summer 2003 with the three-strap shoe.

-

Dress and hat from the Chanel Haute Couture Collection spring/summer 2003. Camillia ring with black and white diamonds and diamond Franges bracelet from the Chanel Fine Jewellery Collection.

Anna Mouglalis

A girl and a dress.

The dress as icon. There are many reasons why in front of a campfire lacey frills and robin eggs’ blue make the image impressive. A little girl will become obsessed, refusing even to wear anything else but a dress. It has passed through the sieve of fashion’s nomenclature and has incarnated numerous spirits. The history is replete with images of Deneuve in Yves Saint Laurent, Loren in Armani, Hepburn in Givenchy. This story is about one player in particular and her dress. Remember the dress vividly, and the woman. The dress holds the impression, the silhouette fades ever so slowly.

Backstage at the spring/summer 2003 Chanel haute couture show this year a distinctly tall unassuming fellow in a pricey track-suit hands Karl Lagerfeld a composite card. Not initially aware of its owner Mr. Lagerfeld looks slightly puzzled. The gentleman matter-of-factly apologizes that Eve would have loved to attend the show: “She’s on tour but she’d love to get together and do something.” “Yes Ehvvve,” he replies in recognition and hands the card to his PR Director.

Haute Couture has a place even in hip-hop. A design house, a dress, and an aspiring starlet have much to achieve together. Jennifer Lopez (apologies for adding to the vast pile of mentions) became famous practically overnight with her green flora Versace sensation. She even thanked Donatella publicly that year at the VH-1 Awards when Versace won designer of the year.

Imagine what it would mean to become the latest corporeal incarnation of the House of Chanel. Anna Moulgalis, who has been “selected” to become the newest Chanel ambassadress, now does not have to imagine. It is real.

When Anna Mouglalis puts on her dress, what will the impression be? This, albeit it looks like one, is not really a marketing formula. The iconic image does fortunately have something to do with the intangible, the ephemeral, the spirit of the times, and the person. All contribute to the longevity and impact of the image. Think of Coco (Gabrielle) Chanel’s image which continues to strike notes of modernity, innovation and strength. What Mouglalis represents still remains to be experienced: the audiences’ initial taste is only a provocation.

In Paris, Anna’s face has already set an impression. Late this January, Anna sat atop stacks of magazines as she gazed out from street corner kiosks. Her impact on the House of Chanel has not only garnered Mouglalis the ambassadress title (only second in their history, and the first since Carole Bouquet). Artistic Director (Cosmetics, Fragrances, Watches) Jacques Helleu has also chosen her for the Allure campaign.

Before the photo session is to begin at 31 rue Cambon, fittingly to be shot in Coco’s former apartment, Anna marvels at how her relationship with Chanel began: “Everything began like something from a movie. After I’d finished Merci pour le Chocolat (2000) I started to get invited to different events. It was like a lightning bolt had hit me. I adored the Chanel creations. I began to run into Karl more and more. Then Hugo Santiago (Anna’s director for Le Loup du Côté Ouest [2002]), at one time an assistant to Bresson actually, decided to use Chanel pieces in the film we were making.” Lagerfeld also provided pieces for Anna’s two other films, La vie Nouvelle by Philippe Grandrieux (2002) and Novo by Jean-Pierre Limosin (2002). “In Novo we used existing pieces but in La Vie Karl designed some specific looks. In La Vie I played a prostitue in Chanel! but I don’t impose my preferences on a film. And regardless, the logo doesn’t cut that kind of social distinction.” She continues in this vein: “I ‘act’ my costumes but my freedom lies elsewhere. I mix them, I dilute them, I adore discrepancies, incongruities.” Anna refuses to be passive, a natural extension of the modern woman Coco introduced to world.

This fascination with incongruities fits well with Anna’s referencing to the French New Wave.

Her relationship with Chanel fits within a larger philosophical context she holds, regarding her work. She likens it to the desexualization of women during the French New Wave, when actresses were asked to act in their personal everyday clothing. “It was all thanks to the cinema that this past October I officially became part of the Chanel family. After two years of collaboration and force of circumstance this came to be. It is unheard of to be part of this renaissance of the actress linked to a fashion house. It was a mythology created after the French New Wave when Godard and Truffaut had their actresses wear their own clothes in films. A costume is so important to a film—it constitutes a dynamic aspect of the architecture of the film.” Anna’s recurring theme is that of active participant in the creative process. To bring the everyday into the film, in this instance via the costume, challenges accepted notions of what the female star represents. Her role is no longer that of dressed-up accessory. She is an active agent in propelling the story forward. Just as at the house of Chanel. Karl affirms the woman as an active participant in his creations as well: “Women can dream of the finest, the most beautiful, and couture puts these dreams into reality. From there, they can make their own decisions.”

Anna’s fascination with incongruities also fits well with her referencing the French New Wave. In these films the emphasis is upon the environment at hand. These directors followed a process of conscious movement towards the antithesis of Hollywood. Anna’s choices as an actor are relevant to this because she is not so much chasing celebrity as she is permanence. “Certain films are produced as if on an assembly line and you have to have a fair amount of cynicism to make them, which I don’t yet have. I know it’s a luxury to refuse, but cinema is a luxury. I’ve only made three films in two years and they correspond to my tastes. I do not have any desire to make films simply to hear the clap of another take. I must be affected by what I do.” A hint of reticence towards a project leads Anna to reject it.

Concerning her newest project, she embraces it as an extension of her role as an actress. “My responsibility is to incarnate the spirit of the house.” It is an enormous responsibility given the almost ineffable nature of the house and of Coco’s contribution to women’s wear in the 20th century. Rebellion and modernity being a common theme in the collections, Coco changed convention. Black no longer carried the moniker of death but incarnated the spirit of rebellion, the liberated woman. Moreover, her reversal of the paradigm of what men’s clothing represented was total. Chanel’s use of men’s clothing in her collection did not simply empower women on a functional level, nor did it simply empower women by proxy. The subtext of her use of pants,tweed, pockets, flat shoes, sportswear, had a symbolic resonance beyond a woman in men’s clothing. Chanel accomplished for herself and eventually for other women the image and reality of the strength of a man in women’s clothing. This resonates on a deeper level. It is not the clothes which hold the power but the woman in them—at this point the appropriation is complete and the liberation achieved. Lady Amanda Larleck, “sparring partner” to Karl Lagerfeld, sits down for a chat after this season’s haute couture show and echoes this idea. She clarifies that the Chanel and Mr. Lagerfeld’s aesthetic are one, and that his approach is not one of an archivist continually subscribing to the images perceived to demarcate the parameters of a brand. “Karl has the same goals as Chanel. The common aesthetic is that of modernity, which is of the moment. It is a live, lean animal whose driving force is the grace in its movement. Karl understands the culture women live in and at the same time the demands and rigours of women who want to dress beautifully without the necessity for six handmaidens.” She smiles and laughs: “Corsets would never appear in a Chanel collection.” Lady Amanda continues by making a clear distinction between image and icon building in her analysis of the House: “It would be sad to discover that the power of a brand is in its image and not in its work.”

Anna’s sentiments towards her own physical appearance or image run parallel to this. Her own beauty is irrelevant. The criteria upon which she chooses to be judged is the quality of the work. This notion of quality is never overly stated—doing so may actually disempower the concept—but it is present in the cumulative effect of her choices. During her formation at the Conservatoire National Supérieur d’Art Dramatique de Paris, amongst other trials, Anna would hear, more than once, that with such a grave voice she would never be cast as the leading ingénue. Relentless were the attempts to raise the timbre of her voice, unflinching was her desire to maintain it. Once Claude Chabrol (who directed Anna in her first major film, Merci pour le Chocolat) revealed the potency in the paradox of a vulnerable beauty underscored by a grave, almost husky voice, the commercial film world had learned its lesson and Anna was left to refuse the offers one by one. She focussed her choices and chose her roles with directors fitting what she terms the nouveau Nouvelle Vague over the yellow brick road to celebrity.

If Anna’s choices do not reveal her understanding of the entrenchment of an icon then Lagerfeld can overtly attest to the phenomena that has beset Paris: “The voice of Jeanne Moreau, the power or Anna Magnani, the presence of Ava Gardner.” Her beauty and her intellect (accepted in hypokhâgne—a preparatory class to the highest degree in literature and philosophy at the Lycée Jules Ferry) are met equally by the force of her romanticism.

“I ‘act’ my costumes but my freedom lies elsewhere. I mix them, I dilute them, I adore discrepancies, incongruities.” Anna refuses to be passive, a natural extension of the modern woman Coco introduced to world.

She is “fascinated by myths, the grandes histoires where love and art meet.” She applies this philosophy to both the cinema and couture. It is apparent in her veneration of the clothes. She muses at the details inside a cuff, at the eroticism evoked by the space between this cuff and a gloved hand. It is an understanding of the work and the brand that complement her as ambassadress. In the changing room as we are preparing for her shot with the pink tulle dress, she stops and marvels at the detailed, delicate trim along the hem and the uncommon attention that was given to the inside of the garment; all the while slightly concerned that she may not fit it properly.

This intense star with subtle self-consciousness makes for a type of elegance that is vulnerable and of this earth. She can represent the dream of the icon but an incarnation that has stepped down from the pedestal. Mademoiselle could be proud of this evolution in the modern woman.

The thematic thread in the questions reporters asked Lagerfeld backstage after his haute couture show this spring is about haute couture’s very relevance. “Was Haute Couture dead?” Each time he patiently, but only just, answered: “Women today want to feel beautiful sometimes, perhaps only once a month or once a year will they want something like a couture piece. But couture is not different from ready-to-wear, or different than jeans and t-shirts. It is all part of the same thing, wanting to feel and look beautiful. Couture is the very top of fashion, but it is not at all irrelevant. It is in fact extremely relevant. Couture is still extremely important to show the possibilities, to show dreams come to life.” This definition seems fitted for the new ambassadress. Anna Mouglalis’s appeal is relevant. Her ability to facilitate her own style while remaining true to a sense of refinement often finds her in jeans matched with sky-high elegant heels. Her use of jewellery is subtle but present. She understands the brand so much so that she is not afraid to create within it. This is an important distinction of the Chanel woman—one would think that a spirit such as Coco’s would insist that a woman possess a unique signature.

Anna reiterates this idea when describing her role for the House: “I am obligated to nothing.” This is not a stance of defiance, however, but of mutual respect. She ruefully explains how important this role is to her: “There exists an enormous respect with the House which gives me much strength. Karl’s support gives me an inexpressible amount of confidence.”

This raw vulnerability is partly what constitutes the appeal of Anna Mouglalis. There can be no artifice in this type of elegance or in this perception of the world. It embraces and reflects Lagerfeld’s, and by extension the House of Chanel’s, philosophy on haute couture and, as an attendant, elegance. A jean and t-shirt as elegant. To embrace the common, the everyday, to understand the beauty in the banal and to understand the beauty in les ecarts from the convention. It makes Lagerfeld’s work in haute couture and Anna’s in film, all works in art, a work of hope, of faith. The aspiration towards beauty, the desire to possess it, the understanding it requires to appreciate it facilitates progress, evolution, creativity.

In Greece, where Anna’s roots are found, there exists a canon of myths. There is a story of a beautiful nymph who steps down from her pedestal, puts on a dress and refuses to ever allow her image to be static again. It’s no myth.

Hair: Laurent Bozzy

Make-up: Susan Sterling, International Make-up Artist for Chanel

Styling: Luisa Rino

Shot on location at 31 rue Cambon, Paris in Mlle Coco Chanel’s aparment on January 23, 2003.