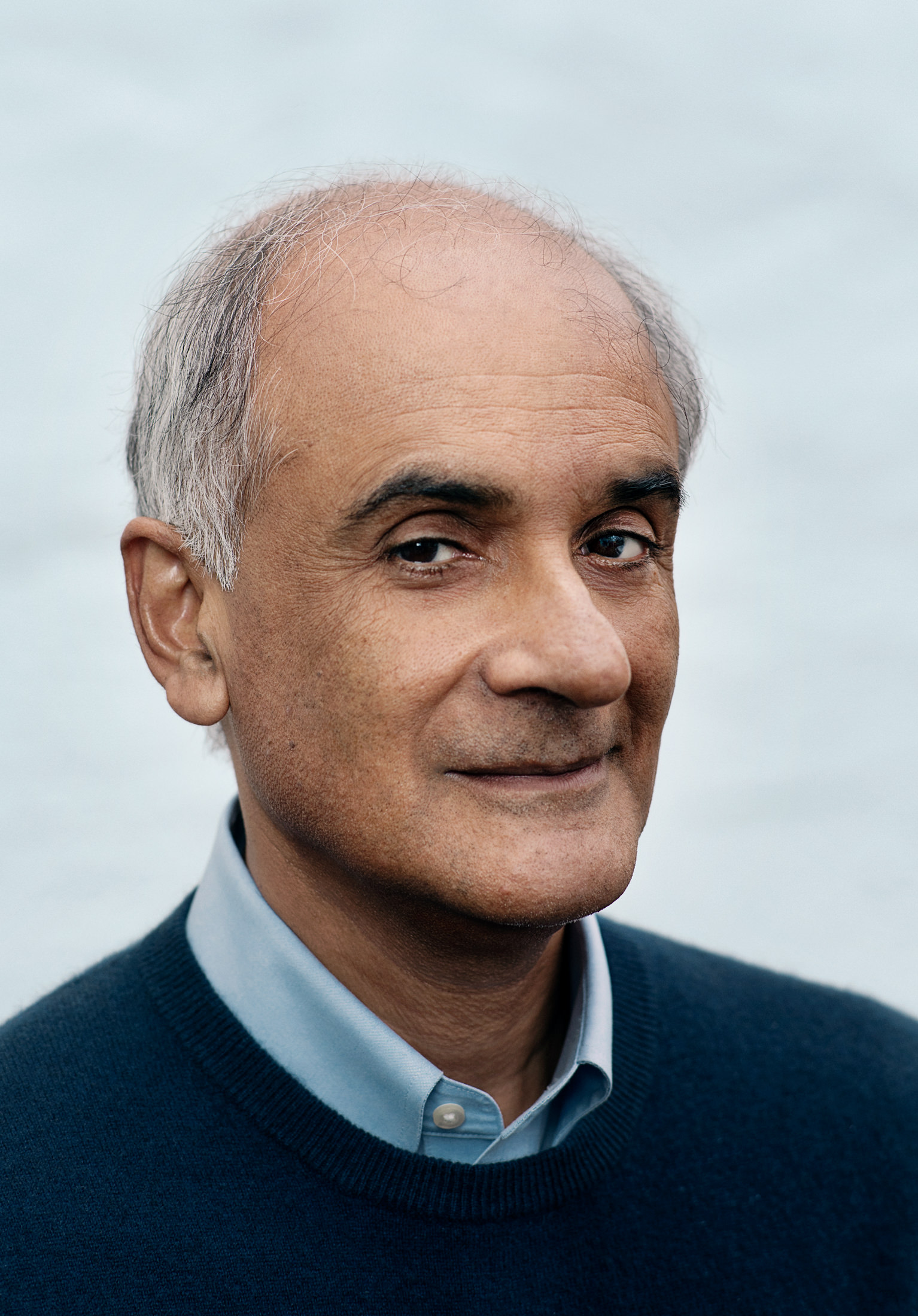

Author Pico Iyer Meditates on Love, Loss, and the Beauty of Life in Japan

Seasons of change.

The American author and professor Joseph Campbell once wrote that we must let go of the life we’ve planned so as to accept the life that is waiting for us. This is the story of so many of us who’ve wandered out into the wider world and been surprised by what we’ve found there. And it’s the story that comes to mind when thinking about the acclaimed writer Pico Iyer.

When the Art of Stillness author was in his 20s, living in Manhattan and working at Time magazine, he enjoyed both success and intellectual stimulation. But, as he began to take on longer assignments abroad and venture farther and farther afield, he became aware of a stirring within—a longing for a different sort of existence. One that was more spacious, more solitary, somehow more streamlined. Iyer’s latest book, the dazzling Autumn Light: Season of Fire and Farewells, is about that life. And about the delight of discovering it in a Japanese suburb with a woman named Hiroko Takeuchi.

“Cities, generally, the more assertive they are, the more they ask you to live on their terms,” Iyer explains as he revisits the turning point where he traded security for freedom, and career for time. “I didn’t feel there was a scope for carving out a different kind of life within that quiet tyranny.” And so, he walked out of bustling Manhattan and into a temple in Kyoto, where the stranger standing next to him turned out to be his wife. It was a move, one might argue, that his life had primed him to make. He was born of Indian descent in England, the only child of two academics. When he was about seven years old, his family relocated to a yellow house on a hill in sunny Santa Barbara, California. He later began commuting, alone, to an English boarding school. As an adult, Iyer has written much about these transitions, and how they shaped his psyche, but today what he’s thinking about most is his arrival in America. At seven, Iyer left behind a red brick neighbourhood in grey, rainy Oxford, where he’d lived his entire life within two square blocks. And found himself in what he calls “the wilderness”, reeling at the vastness of the landscape: the dirt road, the mountain beyond, the fields, the rattlesnakes. The feeling of displacement.

“Nothing I had experienced in England prepared me for that,” he says. “Suddenly moving from a very intimate little drawing into this huge, wide-screen canvas out of a John Ford movie.” The scale, the emptiness, awed him. The presence of nature; the absence of history. It was the 1960s and young people were remaking the world. Arriving there, then, felt to Iyer like a total liberation from the past.

There was a heady freedom to this, and it was a freedom that he came to crave more and more as he grew up and enrolled at tony schools, first Eton, and then Oxford, and finally Harvard, becoming a journalist and rising through the ranks of American media. The freedom that he craved, though, ultimately eluded him in New York. “If I stayed in Manhattan, it would mostly be about meeting famous people and dream assignments and having a nicer apartment and a better salary,” he says. “And none of those were as tempting as freedom and the unknown.”

And so, as the world opened up to him—as he hopped planes and trains and buses to ever-more-remote corners of the globe, penning pieces for Time—he began anticipating his next chapter, “looking around the corner,” mentally “moving from a little office to an open meadow.”

Then, in 1983, he arrived in Japan on a layover, en route from Hong Kong to New York, and took a shuttle into the city of Narita, east of Tokyo. “It was autumn when I first got upended by Japan, and realized that not to live here would be to commit myself to a kind of exile for life,” he writes in Autumn Light. “Almost instantly, for no reason I could fathom, I felt I knew the place, better than I knew my apartment in New York City, or the street where I’d grown up. Or maybe it was the feeling I recognized, the mingled pang of wistfulness and buoyancy.”

Several autumns later, he arrived to spend a year in a Kyoto monastery and forge a life of simplicity and stillness. Of contemplation. One more time, though, life had other plans. After just a week, the monastery proved too similar to his strict British boarding school, and Iyer found himself adrift, standing in Tofukuji, a Zen Buddhist temple, drawn to the woman next to him. Quickly finding, as he writes in Autumn Light, that he was as unable to leave her as he was to leave Japan. It was a homecoming, and one he’s spent three decades exploring, writing about, revelling in.

Living in Japan was like living in an exotic version of England, he muses. “The scale and the customs and the codedness and hierarchy I knew, but in a form that I could never take for granted—it would always be indecipherable,” he says. “Which is the beauty of Japan. I think all of us, in choosing a place, or a life, a career, a partner, we’re looking for that mix of the familiar and the strange.”

In the years since, he’s roamed the globe as a travel writer, reporter, sought-after speaker, and author of two novels and over 10 non-fiction titles, including the seminal The Global Soul: Jet Lag, Shopping Malls, and the Search for Home. Delivering TED Talks and becoming ever-more famous for his exquisite, insightful prose, he’s also spent time with his aging mother in California, regularly retreated into silence at a Benedictine hermitage in Big Sur, and paid visits to the likes of the Dalai Lama and the late Leonard Cohen. But he has always returned to Japan.

“It’s easy to write about falling in love with a person or a culture, and a lifestyle, but maybe the main challenge for most of us is how do we stay in love,” he says. “How do we keep the heart beating 30 years into it?”

This love, though, has endured. And as such, Autumn Light is infused with profound tenderness as Iyer mourns the loss of his father-in-law, plays Ping-Pong at his local club, and passes another glorious fall with Hiroko at their home in Nara (the city south of Kyoto where they now live), marvelling at “the reddening of the maple leaves under a blaze of ceramic blue skies.” All with a quiet sense of satisfaction at having done the one thing that did not come easily for a man perpetually on the move.

“I think a lot of my writing is about the joy of being alone, whether it’s loose in the world or in a monastic setting,” Iyer says. “And that comes very naturally to me. But everything I describe in this book—which has to do with the domestic environment in a small neighbourhood, and settling down—goes against my every grain. And clearly, I thought I needed to go in that direction because I was weak in it, and I needed to learn those skills. I thought my boyhood equipped me very well for being rootless, in flight, in foreign places, and by myself. But not very well for settling down.”

“It’s easy to write about falling in love with a person or a culture, and a lifestyle, but maybe the main challenge for most of us is how do we stay in love. How do we keep the heart beating 30 years into it?” — Pico Iyer

Autumn Light, then, is about finally finding a place to rest for a restless soul, in a small apartment in an unremarkable suburb of Kyoto. “[It’s about] the beauty of nothing happening, and the radiance of the ordinary,” Iyer explains. “And the way in which, in the most boring neighbourhood possible, when you never leave that neighbourhood, you find everything you want, and more.”

Indeed, that space where nothing happens, Iyer reflects, is actually where most of life takes place. Dramatic events, like losing everything in a California fire, as he did in 1990, last just a few hours, but you live with the aftermath for years. “When I look back on my life, really everything important was happening without my planning, in-between the events, in-between the lines,” he says.

“I’m glad, now, to see how much the choices life makes were wiser than the ones I might,” he adds. “Including throwing me into that temple in Narita.”

With this thought, we circle back to Joseph Campbell, who visited Japan in 1955 and published his own book about the country. Iyer had the privilege of spending five days with Campbell in the final year of his life.

“Just yesterday, I was doing a retreat … and I was citing what I think is the heart of this book, which is a line that [Campbell] would quote, probably when I heard him in 1987,” he says. “That life is about joyful participation in a world of sorrows.”

Iyer’s whole body of work, it seems, is about this mix of joy and sorrow. And how, as he puts it, the truth of sorrow is what opens us up to the possibility of joy, however impermanent. “We cherish things, Japan has always known,” Iyer writes in Autumn Light, “precisely because they cannot last.”

________

Never miss a story. Sign up for NUVO’s weekly newsletter here.