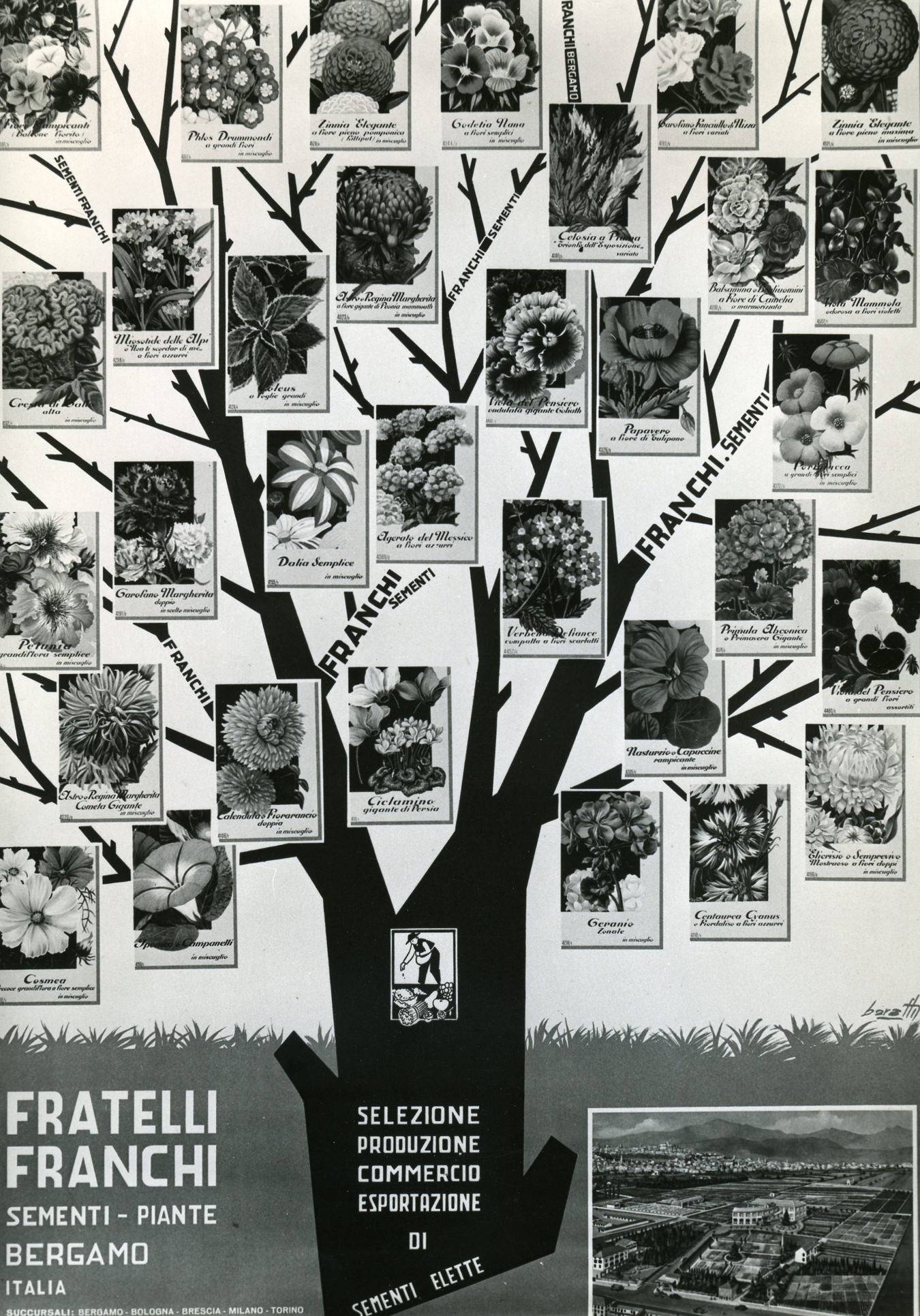

Seven generations ago, when Mozart was penning Mitridate, re di Ponto in Italy, a certain Sig. Franchi was nurturing exquisite seeds, which still endure today in the family firm. It is not for nothing that Italy is known as a nexus of good food, where, at the end of the day, it is all about the seeds.

In his Bergamo office, against a backdrop of over 1,000 varieties of colourful vegetable and seed packets, Giampiero Franchi is quietly passionate about seed provenance. He shares with his ancestors of 1783 an appreciation of living on a long peninsula replete with pockets of ecosystems where unique vegetables and flowers flourish. Take, for example, the lowly courgette. Genoa, Bologna, Florence, Rome, Milan, Naples, Sarzana, Piacenza, and Nizza Monferrato: each region grows courgettes with a flavour unique to that area, producing some of the Franchi seeds exported to over 60 countries, including Canada. Such dedication to keeping heirloom varieties in circulation was behind Franchi Seeds of Italy becoming the first seed company in the history of Slow Food to be invited to take a stand at Salone del Gusto.

Walking with Sig. Franchi through the state-of-the-art seed operation in the Lombardy region, I see young scientists examining germination in the laboratory. The company produces about two-thirds of its total seed quantity (by weight), and contracts out growers from all over Italy for radicchio, cavolo nero (kale), yellow French beans (fagioli rampicante meraviglia), and so on. The smell of seeds emanates from burlap bags, which await individual sorting by a counting machine before the seeds are placed in their packaging sleeves.

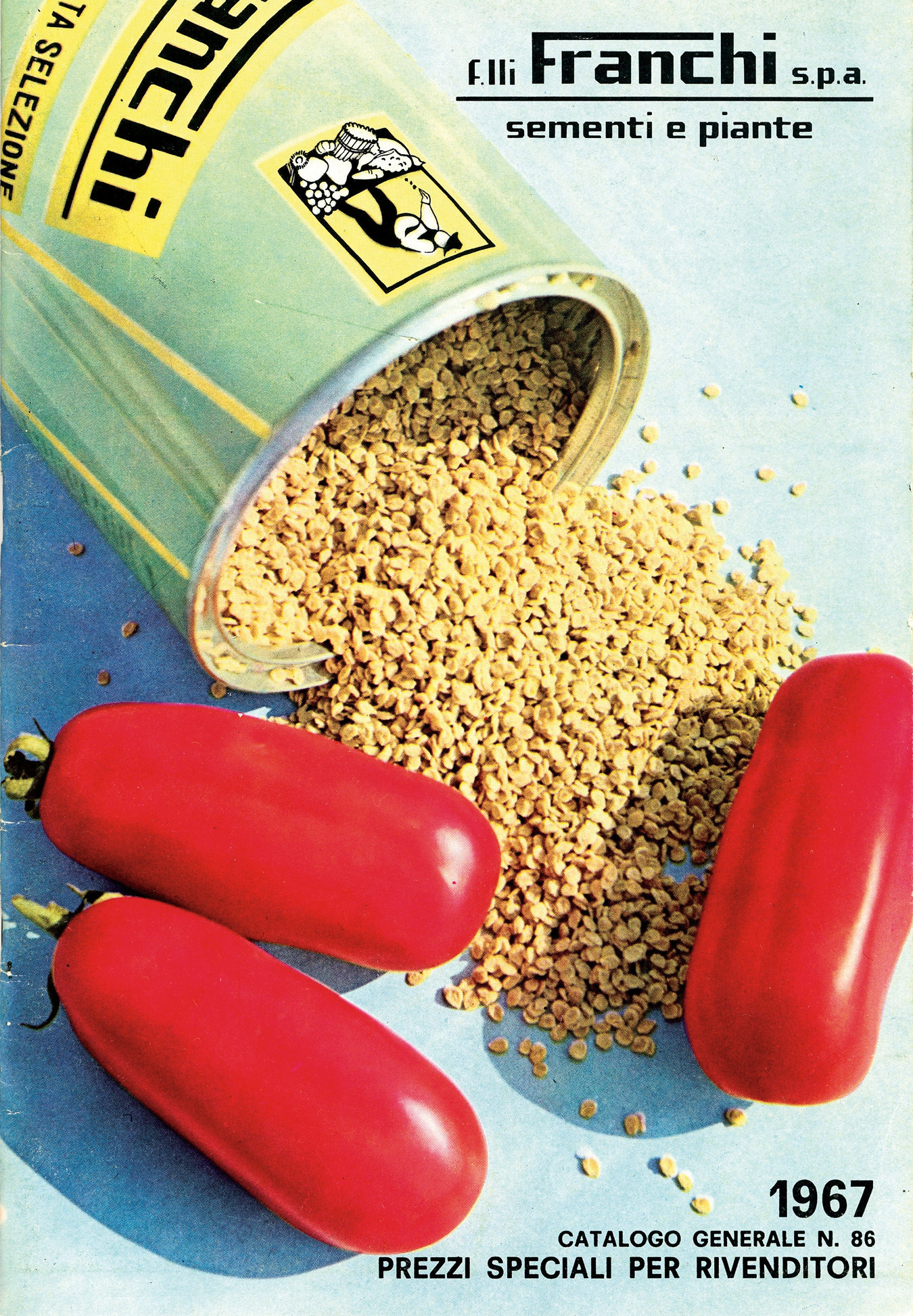

The seed packages are small works of art; for something like luscious Pomodoro Noire de Crimée, they sport an exuberant photo of a fulsome tomato. Inside the packet reside the lowly seeds, which will produce this ode to gastronomy: “round, good sized tomatoes which are slightly scalloped. When they are mature, they will be dark purple in colour.” Outside in the field test area, vegetable varieties unfurl in the Italian sunlight, including the Neopolitan basil with hand-sized leaves that is used to wrap mozzarella di bufala.

Along with managing the taste of the soil, Franchi says it is also a challenge to stay on trend in the seed-growing world. “Arugula has taken off in the last 10 years,” he says, “while purple carrots were in fashion this year, as were purple potatoes from France.” Some growers abroad are also contracted to grow Franchi seed crops, often as a precaution in case nature intervenes in Italy, destroying a field at a crucial moment.

There is a book in Franchi’s office, From Seed to Plate: Growing to Eat Italian Style, by Paolo Arrigo. Leafing through, there’s a line from Arrigo’s nonna Emilia, who lived through the war years creating imaginative meals “out of nothing.” She always concluded a meal with the words “E anchi oggi abbiamo mangiato” (even today we’ve eaten), to which one might add, “thanks to seeds.”