-

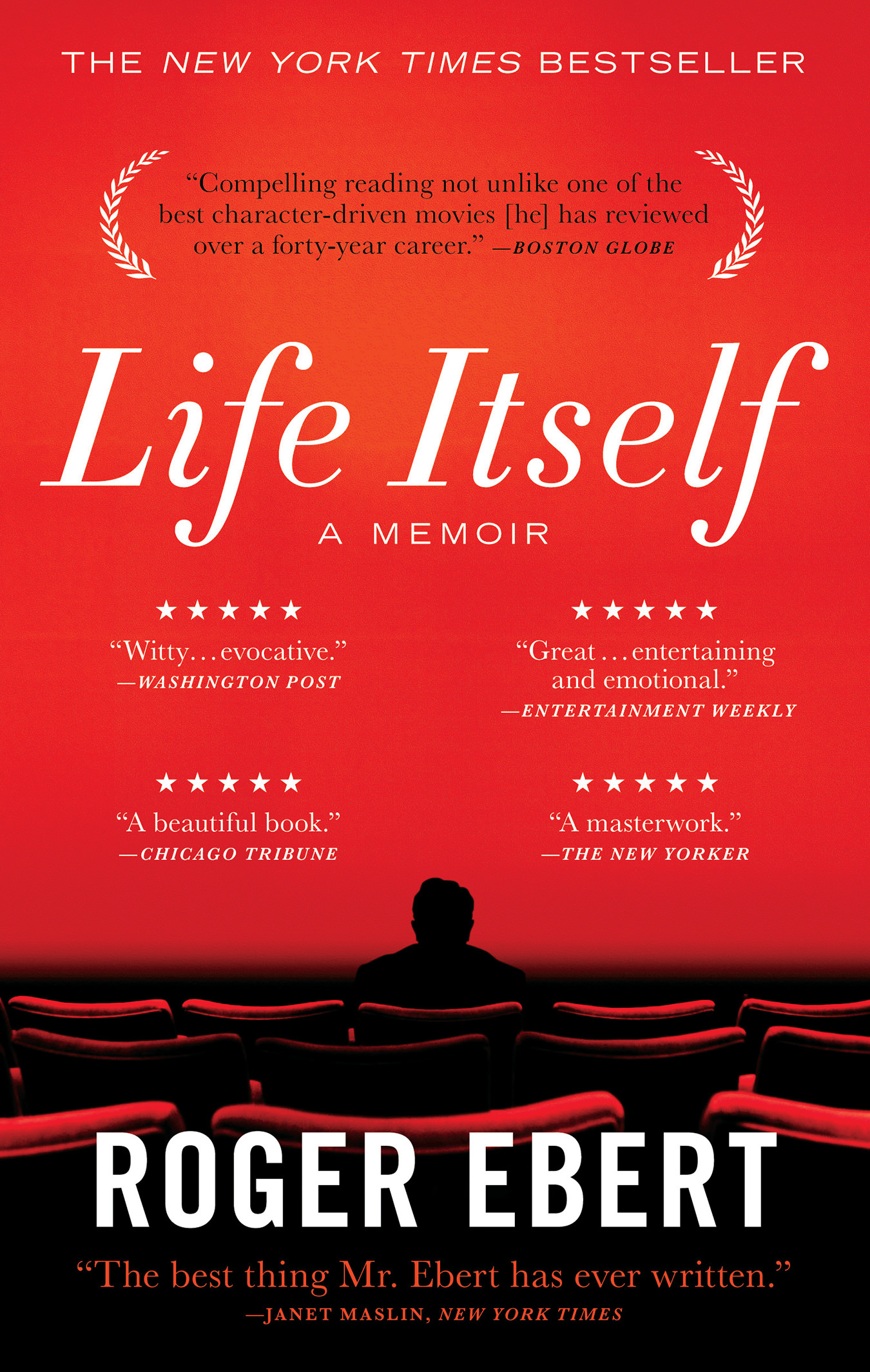

Life Itself by Roger Ebert.

-

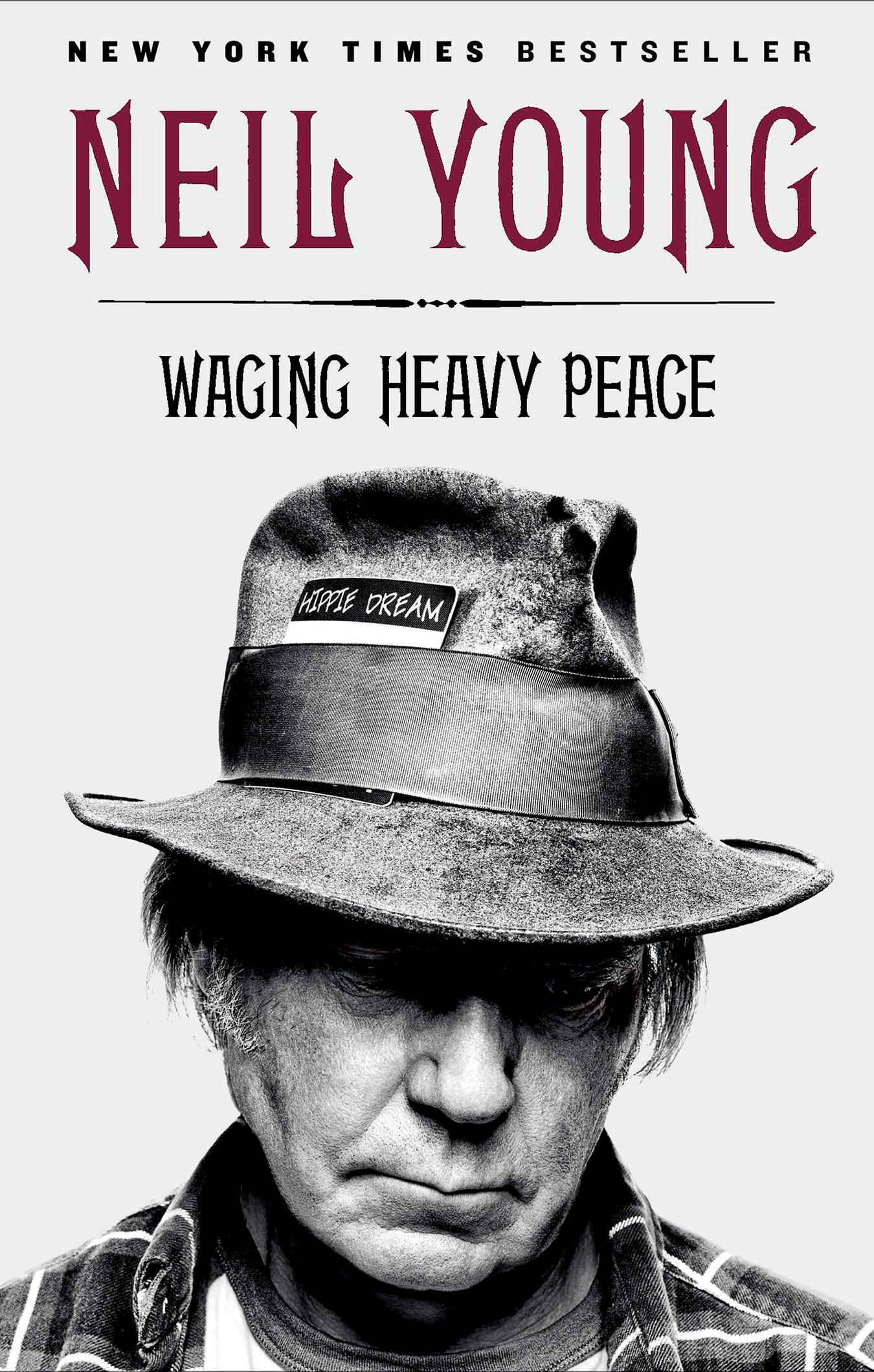

Waging Heavy Peace: A Hippie Dream by Neil Young.

-

On Writing by Stephen King.

Off the Shelf: Masters’ Works

Memoirs by Roger Ebert, Neil Young, and Stephen King.

There are few attributes that I admire more than productivity. I am captivated by those with the ability not just to create, and not just to create well, but to create well and often. In that spirit, I recently read the memoirs of three individuals who are extraordinarily productive, prolific, and dedicated to their crafts: Roger Ebert, Neil Young, and Stephen King. There’s a line in Carl Sagan’s Pale Blue Dot about how “it does no harm to the romance of the sunset to know a little bit about it”; similarly, it diminishes none of the mystique of creators to know a bit about their personal histories, their approaches to their respective crafts, and what makes them tick.

Life Itself: A Memoir

For several years leading up to his death in April 2013, Roger Ebert posted an expansive run of blog entries on his website. The Pulitzer Prize–winning film critic discussed movies, certainly, but after he lost the ability to talk as a result of health complications in 2006, his online presence became an insightful creative outlet. Life Itself: A Memoir,published in 2011, delves even further into his past and experiences; he explains, “In these years after my illness, when I can no longer speak and am set aside from the daily flow, I live more in my memory and discover that a great many things are safely stored away.”

The beginning of Life Itself focuses on his childhood, his family, and his early years in the newspaper business. Midway through the book is a string of chapters describing his relationships and interactions with various individuals, including Werner Herzog, John Wayne, and Martin Scorsese. And then comes a chapter focusing on Gene Siskel, Ebert’s friend and long-time partner on the television show Siskel & Ebert. Ebert memorably describes the competitive but close relationship between the two, and begins the chapter thus: “Gene Siskel and I were like tuning forks. Strike one, and the other would vibrate at the same frequency.”

The discussion of Siskel, who died in 1999 of a brain tumour, marks a turning point, as the last third of the book delves into weightier topics. Ebert discusses his cancer diagnoses (he had a salivary tumour removed in 1988, but was warned that the cancer “was slow growing and sneaky and might return years later”—which it did, in 2002) and the surgeries that rendered him unable to eat, drink, or speak. This was a condition, he observes ironically, that resulted in “more uses of ‘thumbs-up’ and ‘thumbs-down’ than [he] ever dreamed of.”

Even on the subject of his own mortality, Ebert writes with a self-awareness and maturity that make extraordinary the final few chapters. In particular, the section titled “How I Believe in God” is wondrous in its succinct summary of his thoughts on religion and how he views the world; Ebert’s always-effective writing is elevated to astounding heights. Overall, Life Itself is a remarkable meditation on, well, its title, focusing less on raging against the dying of the light and more on fond recollections of how bright that light had shone.

Waging Heavy Peace: A Hippie Dream

Several books have been written about Neil Young, including Jimmy McDonough’s memorable Shakey. But those are about Neil Young, while Waging Heavy Peace: A Hippie Dream is by the enigmatic musician, and the distinction is significant. Told in Young’s quintessentially unique voice, Waging Heavy Peace provides a rare glimpse into the mind of the elusive artist.

Although it is, admittedly, a bit of a puzzlement in the opening pages. The stream of Young’s consciousness flits from subject to obscure subject; some of the book’s first topics include an extended introduction to his collection of model trains and a description of PureTone (now called Pono), the high-resolution online music service Young’s worked on for the past few years. Yet it’s subtle, what’s happening here, and only revealed when Young (whose father suffered from dementia) divulges that he has stopped smoking marijuana and drinking, because his doctor “sees a sign of something developing.” Later, he asks, “What the hell is that cloudy stuff in my brain?”

The upshot of all this? “I am now the straightest I have ever been since I was eighteen,” Young writes. “The big question for me at this point is whether I will be able to write songs this way. I haven’t yet, and that is a big part of my life. Of course I am now sixty-five, so my writing may not be as easy-flowing as it once was, but on the other hand, I am writing this book. I’ll check in with you on that later.” (He is also unapologetic about his meanderings. “There is a lot here to cover,” he writes at one point, “and I have never done this before. Also, I am not interested in form for form’s sake. So if you are having trouble reading this, give it to someone else. End of chapter.”)

Once you’ve accepted the premise, Waging Heavy Peace hums along as a charming, day-in-the-life monologue delivered directly from the musician’s mind. Young’s random observations (“It’s summer now and the insects are all out”) combine with the occasionally odd cadence (“We had a house on the main street, which was Highway 7, and my dad’s typewriter was upstairs in the attic”) and rhetorical questions (“All good things must pass. Why?”) to create an engaging narrative that is more than a little hypnotic at times. Whether he is describing touring with Crazy Horse (the band Young describes as his “window to the cosmic world where the muse lives and breathes”) or making the film Human Highway with Dennis Hopper and Dean Stockwell (“Every day we began with shooting the script we had come up with the night before. What a blast!”), the tales are fascinating, with the understated delivery so distinctive in Young’s singing voice being appropriately present in his written voice, too. His stories of witnessing and being a part of music culture for more than five decades are told brilliantly and often humorously, such as his mention of one particular rock icon: “I met Grace Slick, who was beautiful, sang great, was topless, and blew my mind.”

Following the publication of the book in 2012, Neil Young and Crazy Horse released a new album, Psychedelic Pill, so it can be assumed that he was able to write again. On the album is a song appropriately called “Driftin’ Back”, a reflection on the past that covers some of the same themes as the book and runs an epic 27 minutes 36 seconds. Waging Heavy Peace is far longer than that, but in some ways it reads like the lyrics to the most Neil Young song ever.

On Writing

Stephen King’s On Writing: A Memoir of the Craft, part memoir and part writing guide, provides an illuminating look at the life and, more significantly, the process and work ethic behind one of the most productive and bestselling popular writers. The brief first chapter, titled “C.V.” (“This is not an autobiography. It is, rather, a kind of curriculum vitae—my attempt to show how one writer was formed”), focuses on the events from King’s childhood through to his early 20s that gave him the opportunity to learn about what he liked doing above all else: telling stories. He also describes many experiences that ended up being the basis for some of his novels, including an extended look at the origins of Carrie, his first novel.

Of especially interesting note was the fact that while he was experiencing some of his greatest success as a horror novelist, King was battling other demons. Substance abuse reigned over many of his novels—to the point that he admits to not being able to remember much from writing Cujo, for example—until his wife, Tabitha, eventually organized an intervention:

Tabby began by dumping a trashbag full of stuff from my office out on the rug: beercans, cigarette butts, cocaine in gram bottles and cocaine in plastic Baggies … A year or so before, observing the rapidity with which huge bottles of Listerine were disappearing from the bathroom, Tabby asked me if I drank the stuff. I responded with self-righteous hauteur that I most certainly did not. Nor did I. I drank the Scope instead. It was tastier, had that hint of mint.

(I think Young might be reassured by King’s belief that “the idea that creative endeavor and mind-altering substances are entwined is one of the great pop-intellectual myths of our time.”)

Later, the book changes direction and heads into how-to-write territory. But along with providing nuts-and-bolts advice (“I hate and mistrust pronouns, every one of them as slippery as a fly-by-night personal-injury lawyer”), King recounts his own process of writing a novel. “Don’t wait for the muse,” he advocates. “As I’ve said, he’s a hardheaded guy who’s not susceptible to a lot of creative fluttering. This isn’t the Ouija board or the spirit-world we’re talking about here, but just another job like laying pipe or driving long-haul trucks.” This advice, along with anecdotes related to his own career and his perspective on literature (including a story about The Stand nearly being derailed by extreme writer’s block, and a solid discussion of thematic thinking), would likely be of interest not just to writers but also to discerning readers of all types.

Near the end of On Writing, King reflects, “Writing is not life, but I think that sometimes it can be a way back to life. That was something I found out in the summer of 1999, when a man driving a blue van almost killed me.” He turns further inward in a postscript titled “On Living”, which details the horrifying experience of being struck while walking along the side of the road. (“Smith [the driver] told friends later that he thought he’d hit ‘a small deer’ until he noticed my bloody spectacles lying on the front seat of his van. They were knocked from my face when I tried to get out of Smith’s way.”) The resulting injuries (which included a “cataclysmically smashed hip,” a leg that was “broken in at least nine places,” four broken ribs, and a chipped spine) and rehabilitation threatened to derail his work, but he was nevertheless able to return to his writing: “Writing did not save my life … but it has continued to do what it always has done: it makes my life a brighter and more pleasant place.”

All told, On Writing serves as an argument for something King expounds early on: “Life isn’t a support-system for art. It’s the other way around.”