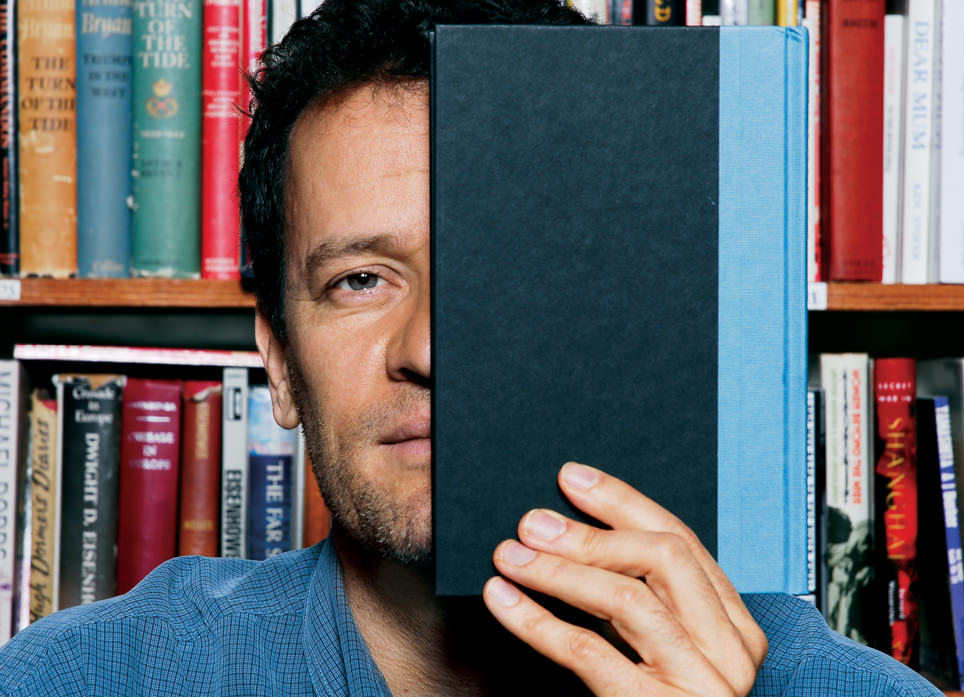

Joseph Boyden

A spirited voice.

Over morning coffee at Balzac’s in Toronto’s Distillery District, Joseph Boyden muses about where he feels most at home. “There’s something called the ‘two-spirit person’ in a lot of First Nations cultures,” he says, “meaning somebody who is never completely in one physical place, in one mental place, and I think I’m a bit of a two-spirit person. Home for me has to be both places—it has to be New Orleans, it [also] has to be Ontario. I would be very incomplete without either of those. It might be a little schizophrenic, but it works for me.”

Boyden looks every bit the cool urban writer, and he is equally at home with his family near the Ojibwe communities of Georgian Bay, or fishing or hunting moose or caribou, which he loves to do with his Cree buddies in the bush of the southern James Bay region. And then there is his life in New Orleans, where he teaches writing at the University of New Orleans (Boyden’s alma mater) and shares a house—a converted corner grocery store in the Mid-City district—with his wife, novelist Amanda Boyden.

Boyden was born and raised in the Toronto suburb of Willowdale, the third youngest of 11 children. His ancestry is of mixed Irish, Scottish, and Ojibwe blood, essentially English Métis. His father, a doctor and the highest decorated medical officer in the British Empire following the Second World War, died when Boyden was only eight years old, and his school teacher mother raised her large family with the help of Boyden’s older sisters.

Despite the suburban location of their home, both sides of the family had close ties to the ways of Ojibwe people in the Georgian Bay area. But it would be even farther afield, among the Ojibwe’s northern cousins, the Mushkegowuk Cree, where Joseph Boyden would find his writer’s voice when he was in his mid-20s. It’s the voice that produced Born with a Tooth, a collection of short stories, followed by the novels Three Day Road and Through Black Spruce, which won him the Scotiabank Giller Prize in 2008. (Boyden has plans for a third novel that would make the series a trilogy.) That voice came naturally to him after he spent several years teaching Aboriginal communications at Northern College in Moosonee, Ontario, and other isolated Cree communities near James Bay. This is the land of Xavier Bird, the main narrator of Three Day Road, the Cree sniper in the killing fields of Ypres and the Somme in the First World War. It is also the home of Xavier’s granddaughter, Annie Bird, one of the voices in Through Black Spruce.

Boyden started writing when he was a teenager in an attempt to express himself. “Writing saved my life,” he says. “My work certainly can be difficult to read because I don’t fear showing life with all of its ugliness.”

Boyden started writing when he was a teenager—a highly sensitive, deeply unhappy, self-destructive teenager. “Writing saved my life,” he says. “When I was a teen, I was travelling down a pretty dangerous road, getting in trouble a lot. Like a lot of teens, especially teen boys, I suffered pretty hard. I had a deep anger that was really sadness disguised as anger. Instead of turning that outward on others, I turned it in on myself and attempted suicide seriously a couple of times, once even throwing myself in front of a moving car.” Boyden turned to writing in an attempt to express himself. “It was very angst-ridden, bad teen poetry,” he says, laughing, “but writing it totally helped.” That escape from destructive teenage furies is the foundation on which he has built his successful writing life.

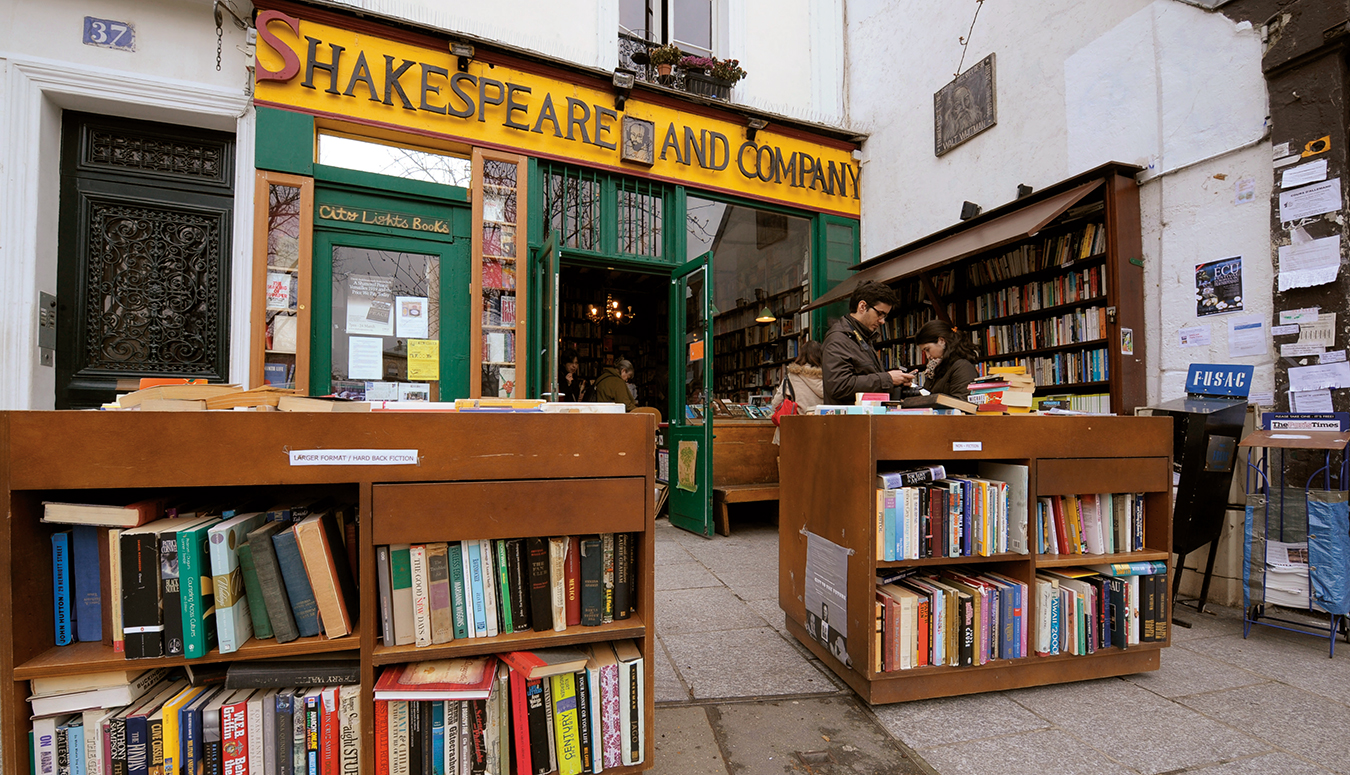

Now, Boyden writes wherever he roams, but his favourite place is sitting across from his wife in his New Orleans home. “She’s a fantastic novelist, a huge grounding influence on me, and also somebody who’s really helped my writing,” he says. “She’s my first, always my front-line editor, as I am hers. We actually wrote our last novels across the kitchen table from each other, which is an amazing experience because we can stop and say, ‘Have you got a second? Let me read this to you.’ We can ask questions, we can bounce ideas—just feeding on each other’s energy, which is really, really great.” He denies any difficulties in sharing the writer’s life with another person. “Sometimes one will get a little more of the trappings of success than the other, but it always balances out. I think it’s wonderful having the two of us in the house, the way we push each other to create.”

Boyden’s latest project is his first non-fiction book, Louis Riel & Gabriel Dumont, a short history of the two Métis leaders. It’s part of Penguin’s Extraordinary Canadians series, edited by John Ralston Saul. For the first time, a writer with Métis roots has written about Riel and Dumont, and for the first time, a major biography focuses on them together. Riel was the deeply Catholic political agitator and visionary leader of the prairie French Métis; Dumont was the leader of the buffalo hunt, a military tactician, an expert horseman, a speaker of six Aboriginal languages, and a master of living on the land. These two very different men came together in the 1880s and led the fight for Métis rights, a fight that ended in Riel’s execution by the Canadian government in 1885.

Boyden is deeply sympathetic to the cause and worked hard to tell the true story through the use of a first-person narrative. “For me, the narrative was trying to get into the heads of these two extraordinary men. Dumont was much easier … He reminds me of First Nations people I know. Riel was more difficult, but I knew I had to try. I wanted to bring back a little of the excitement of the history. I wear the academic hat part of the year [at the University of New Orleans] and, boy, sometimes we academics are really good at taking the life out of the history, and I wanted to bring that back in.

“So I call it a living history. That’s why it’s in present tense and filled with much detail of the time, like the squeaking wheels of the Red River carts—detail for the reader to hold on to. The victors wrote the history of Riel for so many years, and there’s a lot of misinformation and straight-out falsehoods regarding Riel and his mission. He loved the First Nations people, he loved the Métis people, and he loved the white settlers. He was a very inclusive leader—that’s something I feel very strongly about expressing.”

Boyden insists the Riel/Dumont story resonates powerfully for us today. “My belief is that progress [in the late 19th century] took the form of the railroad and the surveyor, and progress stopped serving the people and their communities,” he says. “People served progress rather than progress serving us. And I see that today, with the trampling of rights … I see progress getting really overboard, especially with the environmental situation with the oil industry, in Louisiana with the BP oil spill … and those tailing ponds pouring into the rivers that are poisoning the Indian communities downstream—suddenly progress is trampling the rights of the community again, and First Nations are often the ones who suffer the consequences.”

Boyden is an activist on environmental issues. He has taken time away from his strict fiction-writing regimen to write cover stories on the legacies of Hurricane Katrina and the BP oil spill for Maclean’s. He also joined the board of the Canadian Civil Liberties Association, an organization that champions fundamental human rights and civil liberties. One of those rights is that “Everyone has the right to clean, accessible water,” says Boyden. To that end, he has become involved in the Waterkeeper Alliance, an organization headed up by Robert F. Kennedy Jr.; Boyden is now president of the Moose Riverkeeper Program (the newest Riverkeeper approved by the Waterkeeper Alliance) in the lower James Bay watershed. He counts Kennedy as a friend and got him to come up to James Bay this past summer for a site visit. “What I love about the Waterkeeper organization is that it doesn’t just collect left-leaning tree-hugger people,” says Boyden. “There are hunters, there are fishermen, there are boat captains. It’s the fastest-growing grassroots organization in the world, and for good reason: the message is very clear and reasonable, and very realistic.”

In his writing, Boyden is realistic about his portrayal of First Nations people, and he doesn’t avoid the profound challenges facing Aboriginal communities. “My work certainly can be difficult to read because I don’t fear showing life with all of its ugliness,” he says. He blames a lot of the hardships on the residential school system. “What an idea—‘taking the Indian out of the Indian’. How do you do that—take the children away from their parents and raise them in these cold institutions where often rape is used as a weapon? People have to understand that, and not get burnout from hearing it, because there’s still a lot to be healed,” he says. “But there’s a real beauty there, there’s a ton of positives. So many young people are reclaiming their culture through religion and language and raising their own children. Some of the First Nations people I know who are the best balanced have a foot in the traditional world and a foot in the contemporary world.”

This is Joseph Boyden’s own harmonious balance: the contemporary world of a celebrity writer and the traditional pathways of the Ojibwe and Cree; suburban Toronto, New Orleans, and Moosonee; his Irish-Catholic upbringing and the holistic sacred traditions of Aboriginal spirituality; the life he shares with his wife, and his extended Métis families. He found his voice, came to consciousness on the margins of mainstream culture, and by embracing all that was authentic in himself, found healing.