-

Shelagh Rogers.

-

Shelagh Rogers with her mother in 1957.

-

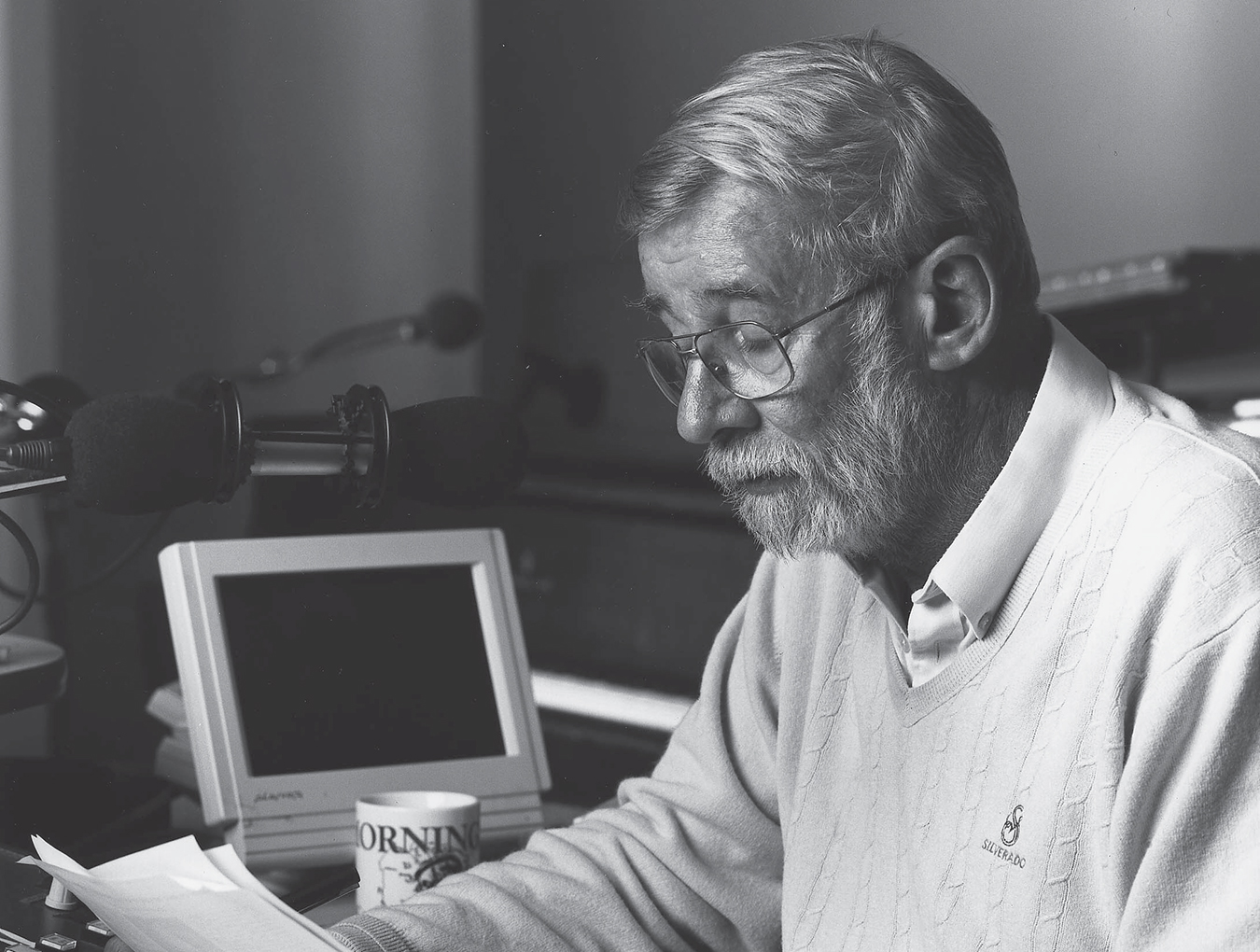

Shelagh Rogers on air with Max Ferguson.

-

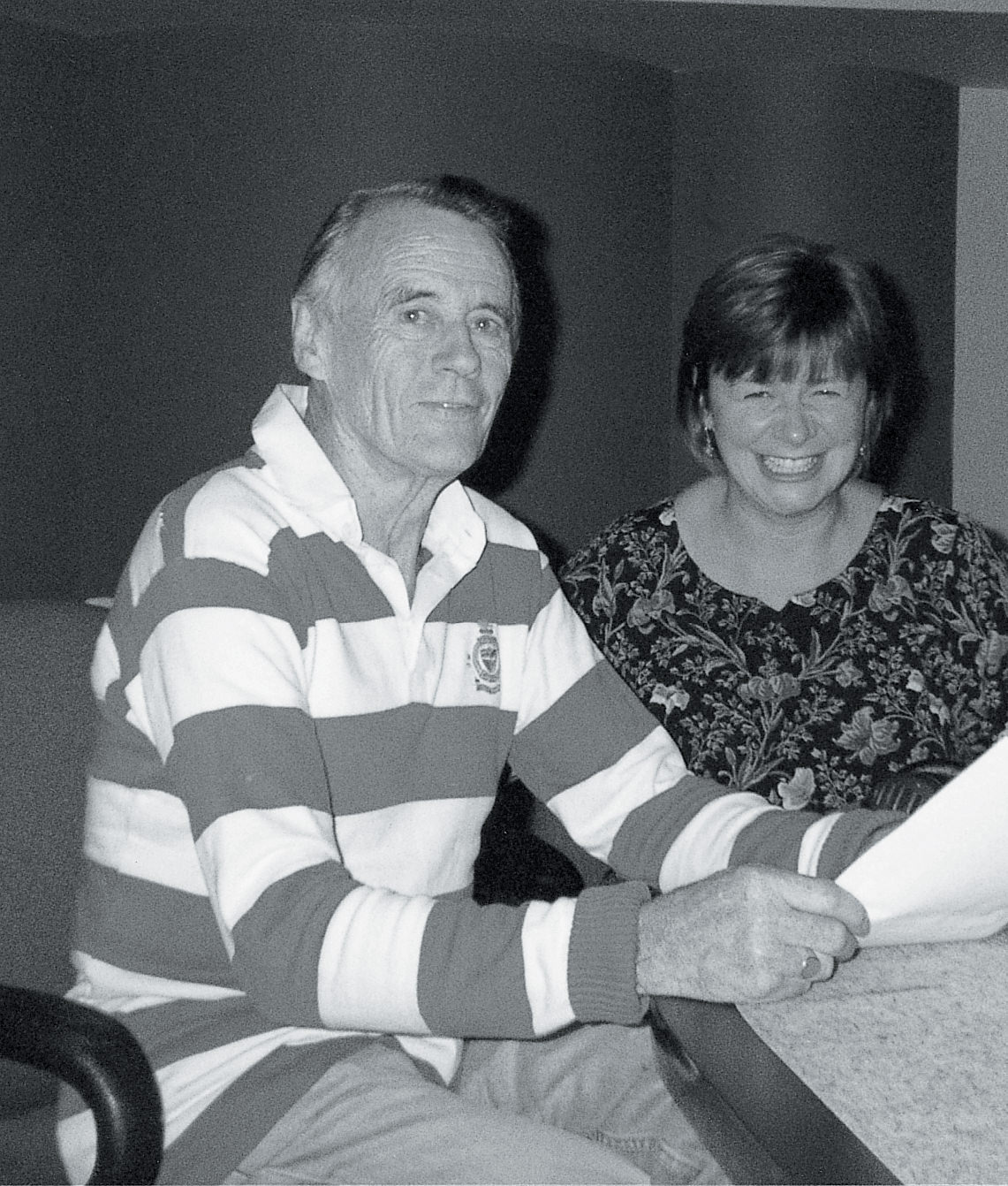

Shelagh Rogers with Timothy Findley, her “worst interview”.

-

Shelagh Rogers serving as Town Crier in her village home.

-

Shelagh Rogers hiking the West Coast Trail with her lucky CBC tee-shirt.

-

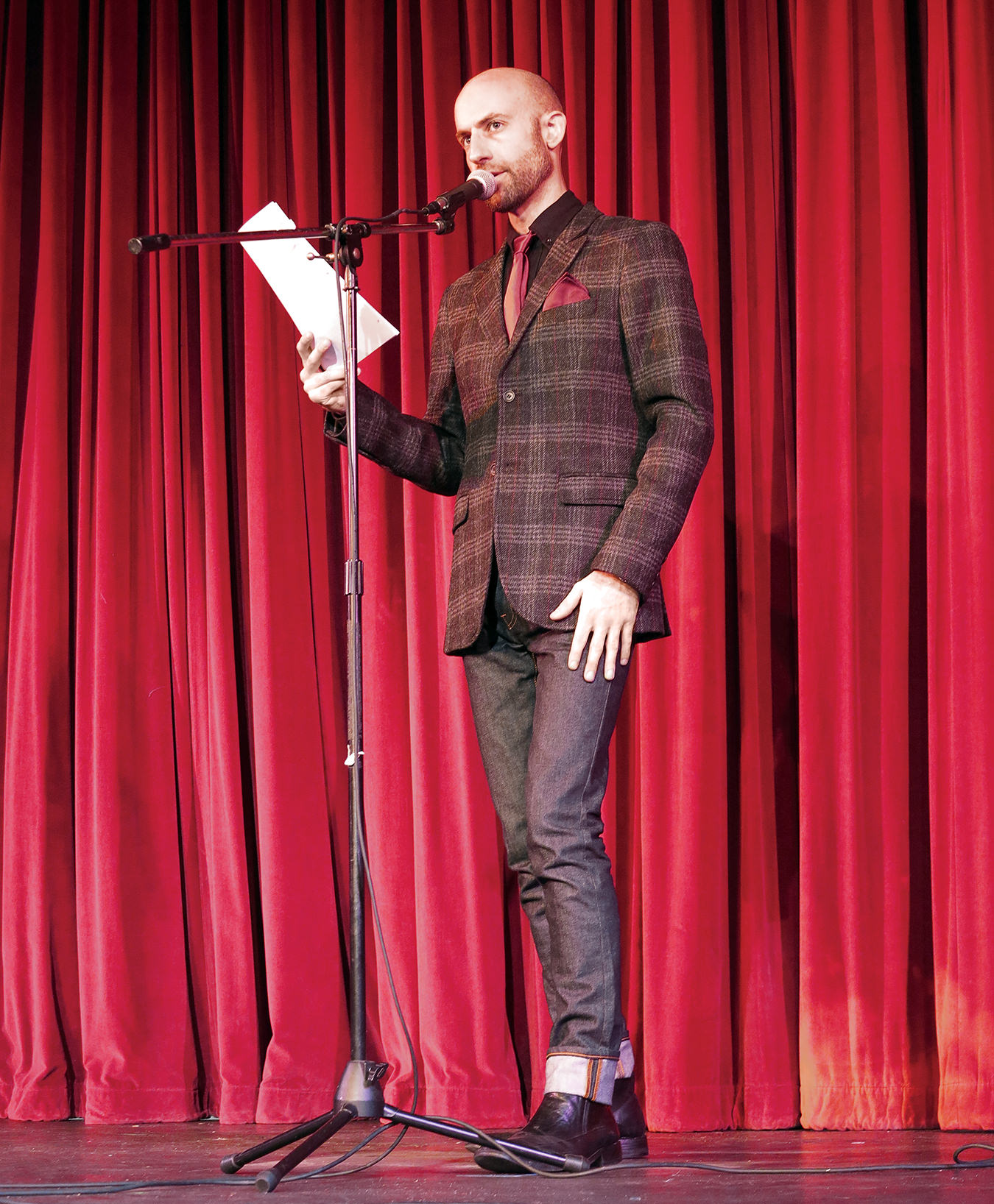

Shelagh Rogers receiving the John Drainie Award. Photo: Kodak Canada.

-

“I wouldn’t mind being remembered as someone who had a great laugh,” says Shelagh Rogers.

Shelagh Rogers

Sculpting on air.

Summer 1980: A tall, fit woman in her mid-twenties is hiking Vancouver Island’s daunting West Coast Trail. A graduate of Queen’s University with a major in arts history, she has gone on to host music shows, country to classical, at a Kingston radio station, moonlighting as a TV weather girl, complete with funny hats. On the trail she wears a T-shirt emblazoned with the red CBC logo (dubbed “the pizza”). Shelagh Rogers is not yet a CBC employee, but before leaving for her trek, she had applied for a job with Mother Corp. in Ottawa. She brought the shirt for good luck. “Every step I took, I thought ‘I’ve got the job; no I haven’t.’ I grew up in a CBC household, and once I started working in broadcasting, I thought it would be neat to work there. But I had no illusions. I didn’t think I was CBC material.” At the end of the trail, there was a message offering her a position as a CBC staff announcer. “I was thrilled out of my head. They also doubled what I was making in private radio. What I didn’t realize was that it was the very minimum they could have offered me. Welcome to the CBC.” Shelagh punctuates the story with her trademark laugh.

Autumn 2000: Flash forward twenty years and 3,000 miles east to the Metro Toronto Convention Centre. It’s the night of the Gemini Awards, Canadian broadcasting’s annual gala tribute to its own. Shelagh Rogers is about to receive the John Drainie Award, named for the consummate radio actor, and presented each year to an individual who has made a significant contribution to broadcasting in Canada. This time it’s going to a woman not yet 45 and still very much in mid-career. And another classic Shelagh moment is about to unfold. She arrives early for hair and makeup, but without her ticket. The security guard doesn’t recognize her and refuses to let her pass. “I looked around for someone who would know me, and who did I spy but John Doyle.” Doyle, the acerbic television writer for The Globe and Mail, had savaged Rogers’s performance as successor to the venerable Elwy Yost on TV Ontario’s Saturday Night at the Movies. “I shook his hand and asked him to vouch for me, which he did. And I felt a sort of evaporation. He was a normal human being, not a devil, and totally entitled to his opinions. John made me think a great deal about what I did, and, in some instances, I actually agreed with him. I was chastened by his columns. I say this knowing I will probably never again venture into the world of television to host a program.” And again she laughs.

Those two moments, and the way she describes them, sum up a lot about Shelagh Rogers: the seemingly contradictory but perhaps essential blend of ego and insecurity, balanced by penetrating intelligence, down-to-earth practicality, human sensitivity, boundless energy, and a wicked sense of humour.

Shelagh Rogers has been host, guest host or participant on innumerable radio and television shows: CBC Morning, Metro Morning, For Your Information, Mostly Music, Stereo Morning, State of the Arts, The Arts Tonight, Speaking Volumes, Morningside, Richardson’s Roundup, Take Five, On Stage at Glenn Gould Studio, The Max Ferguson Show, Basic Black, Imprint, Saturday Night at the Movies … the list goes on and on.

Last Labour Day, she celebrated her twentieth anniversary with the national public broadcaster by hosting her first edition of Radio One’s flagship program,This Morning. It was broadcast live from Ottawa’s Byward Market, and it was old home week. Shelagh grew up in the nation’s capital and began her CBC career there. The mayor declared it “Shelagh Rogers Day,” and guests included CBC President Robert Rabinovitch and her public school gym teacher. For Shelagh, it was a moment of sweet revenge. As she said on the air that day, “I no longer have to put ‘sitting in for’ after my name.”

Three years earlier, when Peter Gzowski stepped down as the beloved host of This Morning’s predecessor, Morningside, many people assumed that Shelagh Rogers was his natural successor. She had appeared more often on Morningside than anyone except Gzowski himself, with several stints as substitute host. She felt she had earned the right to be considered for the job. “I wanted at least the opportunity to audition. What disappointed me most was being uninvited to the game.” Instead, she was assigned to Take Five, a daily five-hour program on Radio Two (“Classics and Beyond”), a shotgun marriage of a listener request disc show and a concert program. She tackled the challenge with even more than her usual drive and commitment, and the ratings soared to record highs.

She consoled herself with the conventional show biz wisdom that it’s never a smart career move to follow an icon. Two years later, she broke her own rule by agreeing to replace Elwy Yost after his 26-year run. “Now I know what it’s like to come after somebody. It’s so hard. The memory of that person is so crystal clear, and will be for years. How dared I have the effrontery to think that I could sit in his chair? You know, when the hero rides off into the sunset, the movie ends. You don’t bring back his stunt double.”

Spring 2000: National Public Radio in the United States approaches Shelagh with an offer to host classical music and current affairs programs. “It was hard to resist. I spent a whole weekend thinking I was going to go.” Her husband flew a Canadian flag in their yard. “I was bawling my eyes out. I didn’t know I was going to say no until I called them. I guess I realized how much we have here.”

While Shelagh was contemplating her options, This Morning was ending its third post-Gzowski season with soft ratings and cool audience response. Changes were in the wind. The prospect of losing Shelagh Rogers may have influenced management. “You’d have to ask them, but I don’t think it hurt. Before the offer from NPR expired, I told them ‘This is what I really want to do, and I think it would be great if you let me do it.’ I was told there was a process to be followed, and I heard that loud and clear. In the past, the process had been very good to me. So I made it clear that this was something I was prepared to get into the ring and fight for.” Ironically, the process in which she put her faith was the same one she’d been shut out of three years earlier.

By now, Shelagh was a more seasoned professional, with a higher profile and a thicker skin. And this time she had the chance to come after the person who came after Gzowski. When Shelagh met executive producer Judy McAlpine in a bar to hear the decision, “I asked her what I should order, Champagne or a triple martini? She said Champagne. I screamed.” That fall she moved into Gzowski’s old studio and left it basically unchanged, except for a couple of personal touches: an exotic wall hanging and a rowing machine.

Throughout her career, Shelagh Rogers has been associated with several of the “grand old men” in Canadian broadcasting—working with and substituting for Gzowski, bantering with Max Ferguson, succeeding Elwy Yost. And what did she learn from them? “Peter taught me how to listen actively, that listening is not a passive verb, and that you’re speaking to one listener at a time. From Max, I learned it’s possible to get into trouble and still keep your job. Radio is a place where there can be a great deal of mischief and play. He taught me that risk was essential. If you don’t push it, you’re going to get in a terrible rut. Sometimes it’s not going to work, and that’s okay, too.”

Through the regular letters column on Morningside and listener requests on Take Five, she learned to build a relationship with her audience and use their input to shape the program. “It’s something I think about a lot, to make sure the listener feels included.” She treats her guests with equal respect. “I take the word ‘host’ literally. I’m a very social being. I love having people in the studio, and I don’t want them to have a bummer in here. I want them to feel good.” Part of her ability to draw the best out of guests is her willingness to put herself on the line. “You have to give to get. What you’re asking complete strangers to do is something enormous. They’ve taken a huge risk just walking in here. If it’s appropriate, I’ll put something on the table too.”

“I made it clear this was something I was prepared to get into the ring and fight for.”

Yet she’s not afraid to be tough. “I’ve believed for a long time that people appreciate being asked challenging questions. They like an opportunity to explain themselves and elaborate on their thoughts. It’s very hard to deny another person’s genuine and sincere desire to want to know about you. I don’t see it as my role to beat people up. Even if this is a person we feel must be held accountable, I still have to respect them. That person is my guest, and I take that seriously. But that doesn’t mean I’m going to back away from something hard.”

Shelagh sums up her approach to interviewing by recalling Aesop’s fable about the contest between the sun and the wind to decide who could remove a traveller’s cloak. The wind huffed and puffed, which made the traveller pull his cloak even more tightly around him. Then the sun came out and shone brightly, and the traveller doffed his cloak. Shelagh prefers the sun’s approach.

For many years, there were doubts in some quarters of CBC Radio about Shelagh Rogers’s abilities as a journalist. She admits “the ‘j’ word has haunted me at various points in my career.” Though she had hosted local current affairs shows, she was associated primarily with “softer” cultural fare. That’s one of the reasons she was attracted to This Morning. “I want to be part of a national dialogue, a conversation about this country. Of course, it’s an artificial conversation. It has a very strong focus and a very clear shape. In a real conversation, you digress; that’s what people do. And I want to incorporate some of that spontaneity.”

She believes she’s overcoming the stereotyping and reservations. “Just because I laugh and enjoy what I do doesn’t mean I don’t take it seriously.” Her take on broadcast journalism is the same as John Donne’s view of religion: it’s a serious business, but not a solemn one. “It’s sometimes light-hearted,” she says of her work, “but it’s not light, and certainly not ‘lite.’”

Journalism is often equated with conflict and confrontation. Shelagh sees it differently. “‘Journalism’ is etymologically related to words like ‘jour’ and ‘journal.’ It’s about daily life and about telling stories. What journalism means to me is finding the stories, both the big ones and the little ones, and telling them well. Out there in the air are all these good ideas and good stories. What we’re doing is sculpting with air.”

Public appearances are an inevitable part of the broadcast star’s life, and Shelagh seldom declines an invitation. On stage, she sometimes dons a gown worn previously by jazz singer Salome Bey, or a glittering jacket formerly used by country star Tommy Hunter, both ensembles now on permanent loan to her from the CBC wardrobe department. “How do I look?” she’ll ask the charmed audience, pirouetting like a runway model. “We’re recycling your tax dollars. I haven’t asked for a new outfit in years.” It’s a shameless piece of schtick and a great ice-breaker. But for Shelagh, it also makes a point. “People want to come up afterwards and touch it. They love to reach out and touch the CBC.”

Wherever she goes, she’s likely to be recognized. The day before her debut on This Morning, Shelagh and an old friend were strolling in a wooded area of Ottawa. “I was musing aloud about what the new job was going to be like and I was expressing my insecurities, my sense of impostor syndrome.” She thought they were alone and unheard. Suddenly a couple approached her with the familiar “You’re Shelagh Rogers, aren’t you?” As a result of encounters like this, she has learned that “I have to be very careful about what I say in public. Especially since I can broadcast without a transmitter. I know how to project, but I don’t know how to whisper.”

Shelagh Rogers has done radio and she’s done television, and she’s clear about which she prefers. “I love the intimacy, the one-on-one of radio. You’re inside someone’s head, creating pictures in the mind.” She might almost say that she enjoys being exposed and hidden at the same time. There’s a personal side, too, which she confronts head-on: “I have a body that’s built for comfort, not for speed. It’s definitely a body for radio. I was destined not to be small. I fought with that for many years, especially when I was on TV.” The fact that she’s prepared to talk about it seems to confirm she’s come to terms with it.

Shelagh Rogers’s weekday life is focused almost exclusively on work. She spends it at her pied-à-terre, an austere studio apartment in Toronto, which she describes as a “tiny monk’s cell.” Here, the routine is unvarying, if not downright boring. The alarm sounds at 3:45 a.m., then again at 4:15, and her feet hit the floor. She has breakfast (always a cheese scone), does the show from 8:00 to 11:00 Eastern Time (for the Atlantic feed; the program is heard from 9:00 to 12:00 across the country); eats lunch, if she’s lucky (always a tuna sandwich), after which there are items to tape. Then it’s back to her cell lugging a knapsack heavy with reading and research. A short nap is followed by preparations for the next day’s show. “I’ve had homework almost every day I’ve been at the CBC. But what great homework, like listening to a disc, reading a book, or going to a movie. And they pay you to do it!” Then back to bed, and soon it’s time to get up and do it all over again.

Her real home is in a southwest Ontario village, where she spends weekends, and where she has served as the Town Crier, among other civic responsibilities. She shares it with her husband, a former CBC technician and manager. “I’m learning to separate life from work. I have to. I’m married now, and that relationship is very important to me. You have to work hard at it.” Other cherished members of the family are two miniature schnauzers. They used to be George and Gracie, as in Burns and Allen. Gracie, who came from the Humane Society, died a year ago. Now it’s George and Poppy. Poppy’s formal name: Crystal Lollipop.

The first thing Shelagh does when she arrives home Friday afternoon is sleep. Then there’s usually a communal pot-luck dinner at someone’s home. Their friends are an interesting and varied lot, almost none in the media. The weekend routine revolves around marketing, cooking and gardening. Shelagh also belongs to a quilting circle organized by television and stage actress Cynthia Dale. In the city and the country, she has a strong support network of like-minded women; colleagues, mostly, some going back twenty years and many now scattered across the land, but still in close touch. “I don’t know what I’d do without my friends,” she says. “They are goddesses. I love them desperately.”

Shelagh’s energy is legendary. So is her sociability. But there’s a side of her that longs for solitude, retreat and inwardness. She once planned a career as an art conservator. “I did some volunteer work at an art gallery in Kingston, picking gold leaf out of old gesso frames. Nice, quiet, solitary work. No interaction with other human beings.” Her spiritual life has included periods of intense belief, punctuated by times of doubt. “It’s a quest, and I think the journey is very important.” She expresses admiration for the work of Christian activists like Jean Vanier and Lois Wilson and such writers on spiritual subjects as Thomas Moore and Kathleen Norris. Her father instilled in her a love of the outdoors, and she still hikes and canoes. “Being in nature is a wonderful solace. It’s what fills you up again.”

“I want to be part of a national dialogue, a conversation about this country.”

And yet, Shelagh Rogers always seems happiest when she’s busy doing something. She got involved in the politics of her village by joining an unsuccessful fight to save an historic bridge. “That was my big awakening. You can’t take being a citizen for granted. You have to work at it; you have to participate. Democracy is an active exercise.” She does fund-raising for Frontier College, whose mission is to spread literacy by reaching out to the most isolated and disadvantaged members of society where they live and work. The day we spoke, she was rushing off to a meeting to plan the college’s annual Bonspiel for Literacy. Among other things, she’s the organization’s poet laureate. “Sure, I’m a published poet. But look where I’m published: The Ontario Curling Review.”

Generosity is in her genes. “I come from a long line of people who got involved. My great-grandmother campaigned for welfare for World War One veterans, and went on to become the first female MLA in Manitoba. I have a great-aunt who was a Member of Parliament for Winnipeg North. My mother has always been involved in community issues; she started the first recycling program in Ottawa and helped launch a business for people with disabilities. My late stepfather started Project 4,000, which brought four thousand Indo-Chinese boat people to Ottawa and found jobs for them. This was a man who did not believe the world ended at your doorstep—a very committed, very spiritual man. He made my world bigger.”

Shelagh inherited other things. “There was a lot of music in our house. My mother had been an organist, and plays the piano magnificently. My father was a real jazz buff, and gave me a lot of his old albums. Both my parents were extremely supportive of anything I wanted to do or try. If I expressed an interest in anything, there were lessons the next week. I guess I was a bit of a driven kid.” She studied violin and piano. “I soon realized that I might not be cut out to be a soloist, but I certainly thought at one point I’d like to play in an orchestra.” Her stepfather, who had been close to such prominent British composers as Ralph Vaughan Williams, Herbert Howells and John Ireland, encouraged her musical interests. Together, they would play Handel sonatas.

Other family memories are less happy. Before she turned sixteen, her parents separated. She admits that it was a traumatic time, but “once I stopped fighting it, it was fine. And today, I feel incredibly blessed in my parents’ choice of their next spouses.” As so often happens, what goes around comes around. When Shelagh married, she acquired three stepchildren of her own. Again, the transition was difficult for all concerned. “I’m very close now to my stepmother. I see her as an older sister. But I wasn’t overly gracious when I first met her. I was pretty chilly. So I know how hard it is when the family unit breaks up. I remembered that it wasn’t immediate in my own situation, and I took comfort in that when I became a stepmother. It took a while, but I feel I’m friends with all three of those kids now.”

Shelagh Rogers says she is “bloody happy to be here,” doing what she’s doing. What’s next? “When I finish this stage in my career—I don’t know how long that will be, it’s up to the listener—I think I want to be more reflective, more introspective, not in a starring role. I have vague ideas of pilgrimage, or living and working in a community of some kind to make it better. Someone said that where I am now is a place where it’s possible to help change along. I hope that’s true, and I feel good about that. But perhaps in the future I can do the same thing in a quieter, less prominent, more direct and personal way.” How would she like to be remembered? “That’s a question I’ve asked a lot of people; it’s hard to answer it myself. I think I’d like to be remembered as someone who helped somehow, who made a contribution, who made a difference.”

I wondered if she was irritated by the parody of her patented by Linda Cullen, one-half (with Bob Robertson) of the Double Exposure team. With its exaggerated laugh, Cullen’s caricature emphasizes all those real or perceived qualities Shelagh has sometimes been saddled with: the heartiness, the perkiness, the (to some) insufferable niceness. “I don’t mind it at all,” she assures me. “I got to know Bob and Linda when I was working in Vancouver and I love them. Peter Gzowski told me when she first did it, ‘This means something. If you’re individual enough and important enough to be made fun of, go with it.’”

And returning to my question about her legacy: “I wouldn’t mind being remembered as someone who had a great laugh.” (And of course she laughs as she says it.) “‘She had a great laugh and she’s had her last laugh.’ How’s that for an epitaph?”

Then she turns serious again—but not solemn. “One of the missions of This Morning is to bring out a sense of joy. Joy in the midst of sorrow and tragedy, great issues and significant events, and the stories of ordinary people. I believe in joy as a value, and I believe it is attainable in our daily, quotidian lives.”

Shelagh Heather Sutherland Rogers, long may you give—and receive—that joy.

Shelagh Rogers’s Worst Interview

“My worst interview ever was my first of many encounters with an author. I was 22 years old, and it was with Timothy Findley. He had just won the Governor General’s Award. The publicity bumpf didn’t arrive, so I did it blind. And I hadn’t read the book. I asked Timothy Findley why he’d won the GG. He said for his novel The Wars. I said, ‘You mean you get the Governor General’s Award for a book?’ I thought it was a military honour, not a literary one. Whereupon he started interviewing himself. ‘Would you like me to tell you about so-and-so?’ he would ask. And I just kept saying ‘Yes, oh yes.’ I felt like walking off a plank into Lake Ontario.”

Like all good stories, this one has a sequel. A decade later, when Shelagh was a CBC network host, Timothy Findley met her again on-mike. “He recognized me instantly. Not only that, but I remembered that ten years before in Kingston he had been accompanied by a person who I thought was his driver, but who was actually his life partner, William Whitehead, and who was with him again on this occasion. ‘Oh,’ I said, ‘I see you have the same driver.’ And Tiff (as I am now permitted to call him) looked at Bill and said, ‘It’s the Yes Girl!’ He’s become a really great pal. And so has his driver.”