Canadian Contemporary Artist Michael Snow is Still Going Strong

Forecast calls for more Snow.

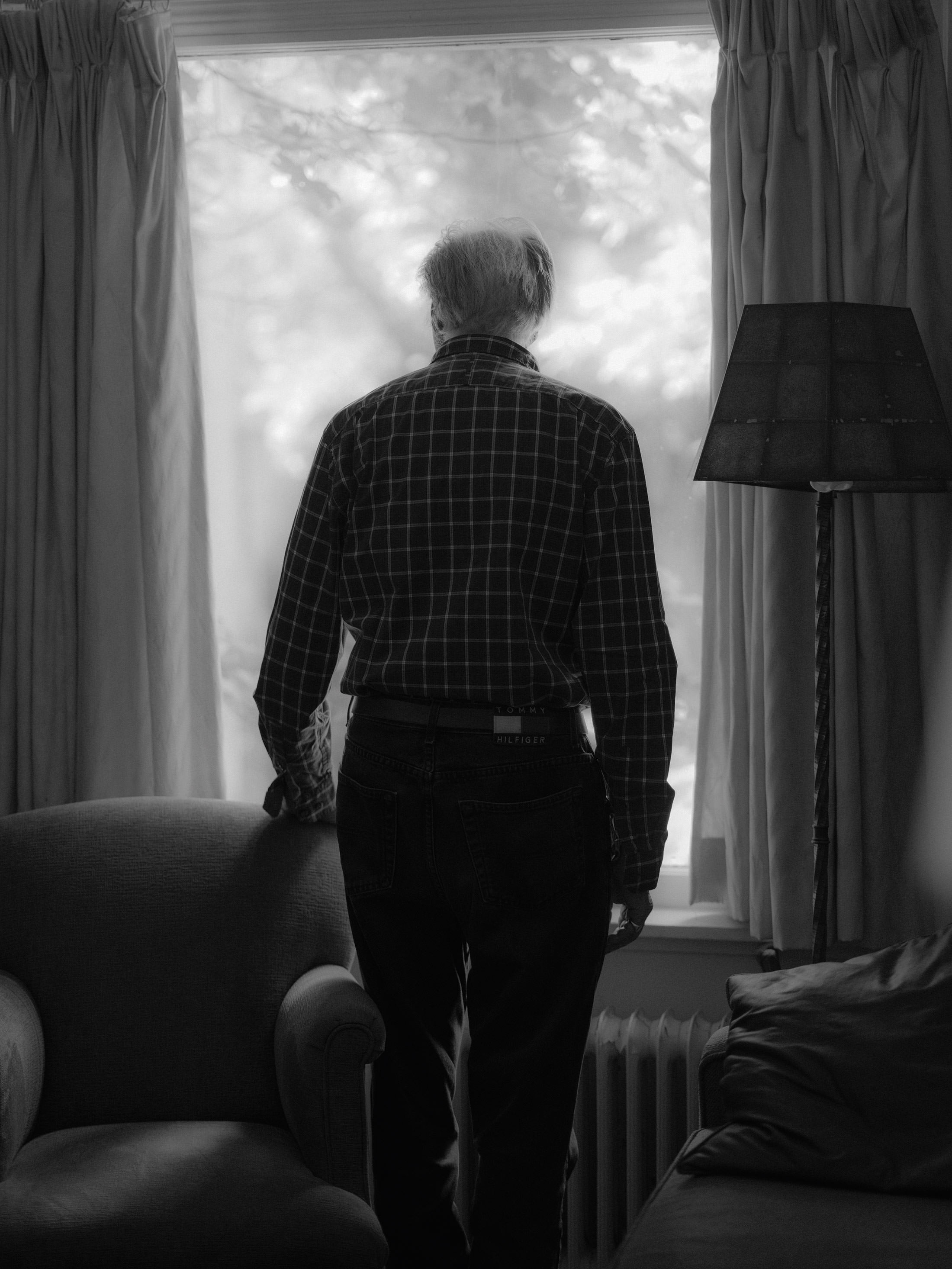

I could start this story about Michael Snow at the beginning of our conversation. But given that the multimedia artist with a 70-plus-year career continues to defy convention, perhaps it is better to start this story at our farewell. We pause in front of a painting he executed decades ago. “It’s deliberately hard to see,” says Snow, shuffling purposefully forward to peer at the barely discernable spray of multicoloured dots hanging behind glass on the wall of his Toronto home, “because it’s about seeing.” The statement seems a fitting end to our lengthy talk exploring the artist’s protean output and unending fascination with modes of perception and visible forms.

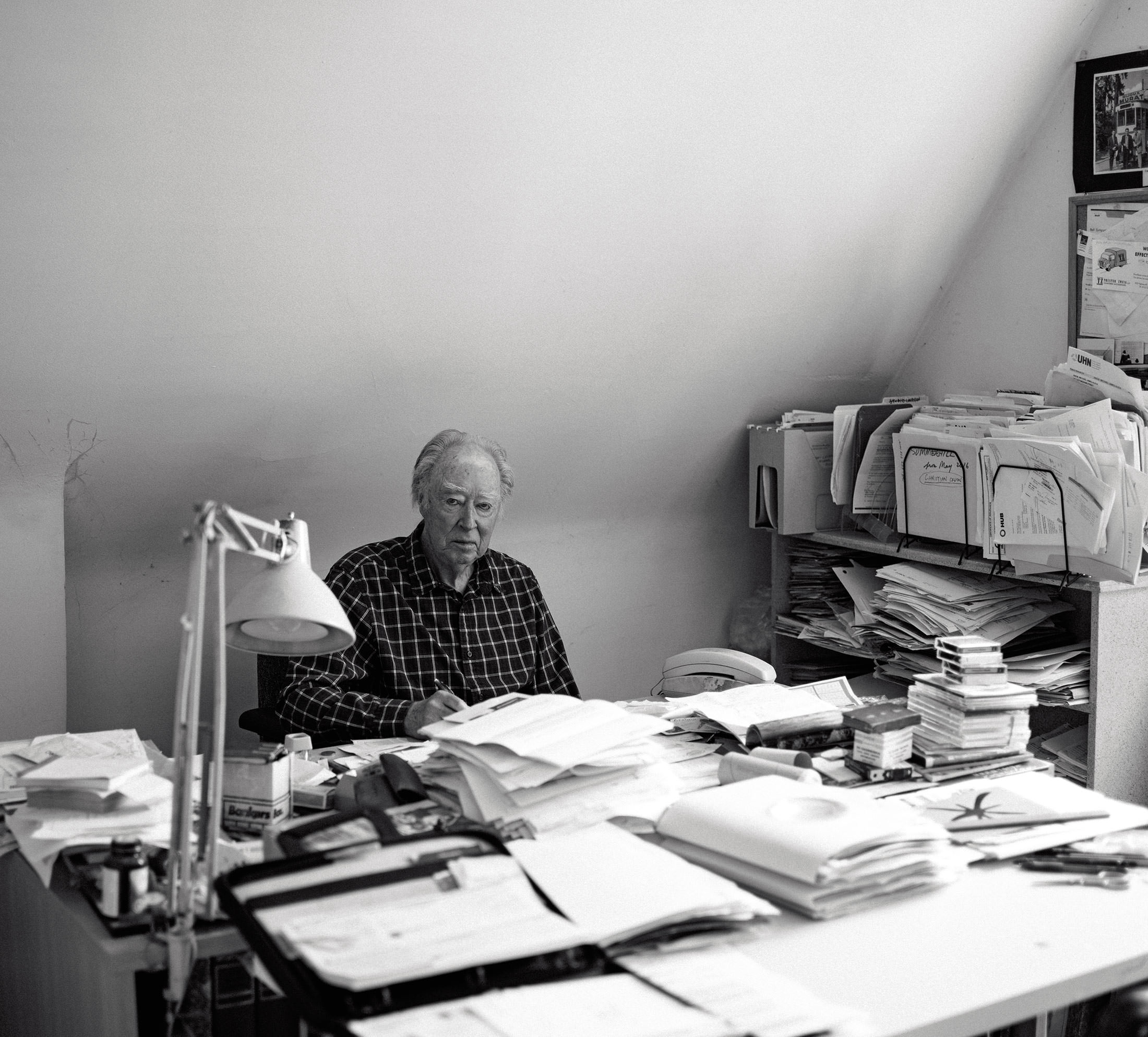

Widely recognized as one of the world’s foremost living artists and a central figure in Canadian contemporary art, Snow turns 91 in December, but he still has you looking and listening in new ways. Age has slowed only his gait. The mind remains agile after years on the front lines of contemporary art, film, sculpture, photography, holography, music, and books. He credits working in a variety of mediums for keeping him vital. That, and a wardrobe of checked shirts, he adds with a sly smile. Humour remains a strong suit.

Educated at Upper Canada College and the Ontario College of Art (now the Ontario College of Art and Design University), Snow was shaped by the jazz music he discovered in his teens and perfected while living for a year as an itinerant musician in Europe in 1952 and New York in the 1960s. He is that rare combination, an artist both esoteric and populist. Born to an anglophone father and a francophone mother, having a dualistic identity comes naturally to him. He is celebrated as much for Wavelength, the landmark experimental film he made from a 45-minute zoom shot inside a New York loft in 1966–7, as for The Audience, the large-scale, gold-painted sculptures of rowdy sports fans he created for Toronto’s Rogers Centre in 1989.

Snow’s achievements are considerable, but they are not all past tense.

A Companion of the Order of Canada, the country’s highest honour, Snow became something of a household name with the launch of his Walking Woman series of stainless steel sculptures at Expo 67 in Montreal, and the casts of Canada geese he hung from the ceiling of Toronto’s Eaton Centre mall in 1979 as part of a public art installation entitled Flight Stop.

Exploring positive and negative space, one of the first Walking Woman works, called Venus Simultaneous and made of canvas and oil paint, appeared in Avrom Isaacs’ Toronto gallery as early as 1962 (it is now in the permanent collection of the Art Gallery of Ontario). The impact of the series on Canadian contemporary art has been huge, observes Gilles Hébert, artist, curator, and former Windsor Art Gallery director and Art Gallery of Alberta executive director. “In the late ’90s, I started a new job at Saskatoon’s Mendel Art Gallery. I visited the art vault, where I came across Snow’s Walking Woman. At first, I couldn’t tell if I was following her or she was following me. I cleaned my glasses and discovered we were all following her—Snow’s influence.”

Snow’s achievements are considerable, but they are not all past tense. Scheduled for release in 2020 by Toronto’s Prefix ICA is a book documenting, through perfectly preserved photographs, his family history in Ontario and Québec is a present preoccupation. Collection de la photographie de ma mère… will consist of 500 images augmented only by what Snow’s mother, Marie Antoinette Carmen Francoise Levesque Snow Roig, wrote on the back of the photos, some of them taken by the legendary Canadian photographer, Joseph-Eudore Lemay, at his Chicoutimi, Quebec, studio. Among the images is a photo of a painted portrait of Snow’s ancestor, Jacques Dénéchaud, a distinguished French surgeon who came to Canada in the 18th century.

Mementos of Snow’s expansive career and life lie scattered in his home, serving as windows into his past.

Snow has an impressive pedigree, but he is far from elitist. For him, art making has never been a specialization. It’s more of an everything, the alpha and omega of all he has lived, loved, and learned. “My paintings are done by a filmmaker, sculpture by a musician, films by a painter, music by a filmmaker, paintings by a sculptor,” to quote what he said about himself more than 50 years ago in a text for the National Gallery of Canada. “Sometimes they all work together.”

They work together because Snow, who studied design for four years at the Ontario College of Art (now OCAD University), graduating in 1952, is intensely disciplined as well as innately talented. Focus is a word he uses frequently during a discussion in which he talks about becoming interested in playing piano after hearing Jelly Roll Morton and other New Orleans jazz musicians on the radio in 1948, and how he learned to make films while working in Toronto with George Dunning, who later directed the Beatles’ Yellow Submarine.

In art school, he was tutored by the college’s then director, John Martin, in the history of modern painting. He discovered Paul Klee—an artist who would exert a strong influence on Snow’s early work—through these private sessions. The 3-D shapes of the Bauhaus design movement also had an effect. As for what else has inspired him, Snow is ambivalent. “Some things just set me off in a direction, an area of possibilities,” he says, by way of an explanation. “I’m not exactly sure how that happens. I can’t go much further than that.”

But if the muse is a mystery, the desire to keep on creating is openly acknowledged. Other 90-year-olds might find wonder in the sheer fact of still being alive. But Snow is not like other nonagenarians. Diminished hearing notwithstanding, he insists on being artistically productive well into old age. He is as busy as he’s ever been and his days remain full, with more than just memories.

If the muse is a mystery, the desire to keep on creating is openly acknowledged.

With so much to do and fearful he might forget all he wants to say, Snow comes carefully prepared for the interview. Settling into a wooden chair at his sun-lit kitchen table, he produces a handwritten document detailing his past, present, and yet-to-come shows, screenings, and publications. It’s quite the list.

Topping it is the performance he will give in a few days with CCMC, the Toronto free-improvisation band he has been performing with since 1974. (According to the artist, the name can stand for many things, such as Crushed Cookies Make Crumbs, or Cynthia Can’t Marry Chuck.) He’s been practising for weeks on his living room grand piano, and it goes off without a hitch. Music continues to be a passion, and he is widely recognized as being quite good at it. In March of this year, the Centre Pompidou in Paris invited him to play a solo piano concert, which he followed with an appearance on a panel discussion at the Louvre concerning his life’s work. “It was well attended,” says Snow, with characteristic modesty. In February, he had travelled to the Tate Modern in London for a rescreening of Wavelength and the world premiere of Waivelength, a new site-specific audio performance made with a frequent collaborator, the improvisational synthesizer player, Mani Mazinani. The previous year, Snow had attended a retrospective of his experimental films and sound installations at Lisbon’s multimedia Culturgest, and another, presented as a looping montage of his film footage, at the Guggenheim Bilbao. Few Canadian artists—living or dead—ever get this level of international attention.

There was also, he continues, stealing a peek at his notes, an exhibition in Barcelona, the Spanish city where, in 2015, Ediciones Poligrafa published a 400-page monograph dedicated to his kaleidoscopic accomplishments, Michael Snow—Sequences—A History of His Art. Then it was back to Toronto for yet another retrospective, this one tied to his 90th birthday, at the Art Gallery of Ontario.

With an agile and impressive mind, the nonagenarian remains artistically productive well into old age.

Snow is “a guy who excels as a musician, a painter, a photographer, a sculptor,” says Paul Dutton, a poet, a vocalist and fellow bandmate who has been performing with Snow in CCMC since the early 1980s. “He’s got no business being so good at so many things.”

And those things are expanding. In 2018, Snow created his first formal musical composition, a commission from the Winnipeg New Music Festival that the Winnipeg Symphony Orchestra performed in the Manitoba capital last January. Before, when he wanted to create a piece of music he would improvise, spontaneously producing pieces like EV∃ a solo piano composition made for Toronto musician, Eve Egoyan, in 2014.

As Egoyan describes it, Snow composed the work twice—each time one-handed—while playing her piano, which has the capacity to transcribe. Her husband, the artist David Rokeby, then created software that would translate the transcription into notation. Though intended for her to play, the piece is more a reflection of Snow’s own playing. (Egoyan had to edit the piece with his permission to be playable with two hands at the same time.) Even still, Egoyan loves it, regularly performing it as part of her repertoire. “I think of Michael as a trickster, disobeying ‘normal’ rules and conventional behaviour,” she says. “He is superhuman, an unstoppable, extraordinarily flexible creator.”

Demand for his work continues. His Michael Snow: Cover to Cover, a 300-page conceptual book first released in 1975 in a limited run of about 1,000 copies, is getting a reprint in 2020. Published by New York publishers Primary Information in collaboration with Light Industry, the 3,000 new copies will retain the wordlessness of the original, in which a series of photographs follow Snow on his wanderings across Toronto to his gallery, where he picks up a copy of the same book. The front and back covers both depict doors that Snow (and presumably the reader) enter and exit as part of the artistic journey. Upending publishing norms (some of the inside images are presented upside down, suggesting a production defect), the book plays with perceptions and audience expectations. It is a classic example of Snow using a given form to create an alternate reality.

“I had these ideas of pushing the bookishness out of the book,” he says, as he thumbs through a first edition of Cover to Cover, today a collector’s item. “It might not be obvious, but it comes out of my other work—making a structural aspect of the medium, making it become like a protagonist. In a way, it’s like the zoom in the film Wavelength. The zoom is a factor; it’s not just something to get you from here to there.”

Asked to elaborate, Snow takes a shaky sip of water before giving a considered précis of how he creates—an art lesson straight from the source. “I have made sculptures as objects that directed the attention of the onlooker to look through a certain thing. That seems to have become an object of interest for me quite early,” he says. “I’ve been interested in the possibility of seeing through to the other side because everything has another side. You just need to know where to look.”

_________

Never miss a story. Sign up for NUVO’s weekly newsletter here.