Lina Bo Bardi Finally Gets Her Due

The Italian-Brazilian architect’s award at the Venice Biennale.

Lina Bo Bardi in the Bardi's Bowl Chair, 1950.Image courtesy of Instituto Bardi.

The Museu de Arte de São Paulo is a museum unlike any other. On approaching from the outside, it looks like a floating monolith with four concrete columns painted fire-engine red to stand out from the surroundings. Guests ascend by elevator or take the stairs up to the main gallery. The appearance has stopping power, but then one realizes the facade is an incredible invitation. Inside, paintings by European masters like Cézanne, Van Gogh, Monet, Renoir, and Picasso seem to float in the centre of the room. Mounted on glass display easels, the paintings shake up the traditional art museum model and invite viewers to engage with the works in a more intimate way.

Lina Bo Bardi at work meeting at MASP. Image of courtesy Instituto Bardi.

The visionary architect behind MASP is finally getting her due thanks to a posthumous Special Golden Lion for Lifetime Achievement award presented at the inauguration ceremony of La Biennale di Venezia on May 22. Though she may not be as famous as Le Corbusier, Mies van der Rohe, Eero Saarinen, and Oscar Niemeyer, Lina Bo Bardi was one of the 20th century’s most influential female architects.

Born Achillina Bo in Rome in 1914, she studied architecture at Sapienza University and after graduating in 1939 moved to Milan. There she collaborated with Gio Ponti and co-directed Domus, in addition to creating her own magazine. In 1946, she married Pietro Maria Bardi, an art critic, dealer, and gallery director. The couple moved to Brazil at the invitation of media magnate Assis Chateaubriand, who hired Bardi to establish and direct the Museu de Arte de São Paulo, which opened in 1947 in part of Chateaubriand’s business headquarters. Bo Bardi designed the museum’s current home on the Avenida Paulista—considered one of the foremost examples of Paulista architecture—in 1958 and its construction was completed in 1968.

Lina Bo Bardi and glass easel with a Van Gogh at MASP construction site. Image courtesy of Instituto Bardi.

MASP’s simple-yet-revolutionary design.

Before designing MAST, Bo Bardi flexed her muscles with the Casa de Vidro, her own residence located in a lush jungle on the outskirts of São Paulo. Like a cross between Le Corbusier’s Villa Savoye and Philip Johnson’s Glass House, it’s essentially a modernist glass box built on stilts and meant to integrate into the surrounding landscape. That same year, 1951, she designed the bowl chair, which Arper released in a limited edition of 500 pieces.

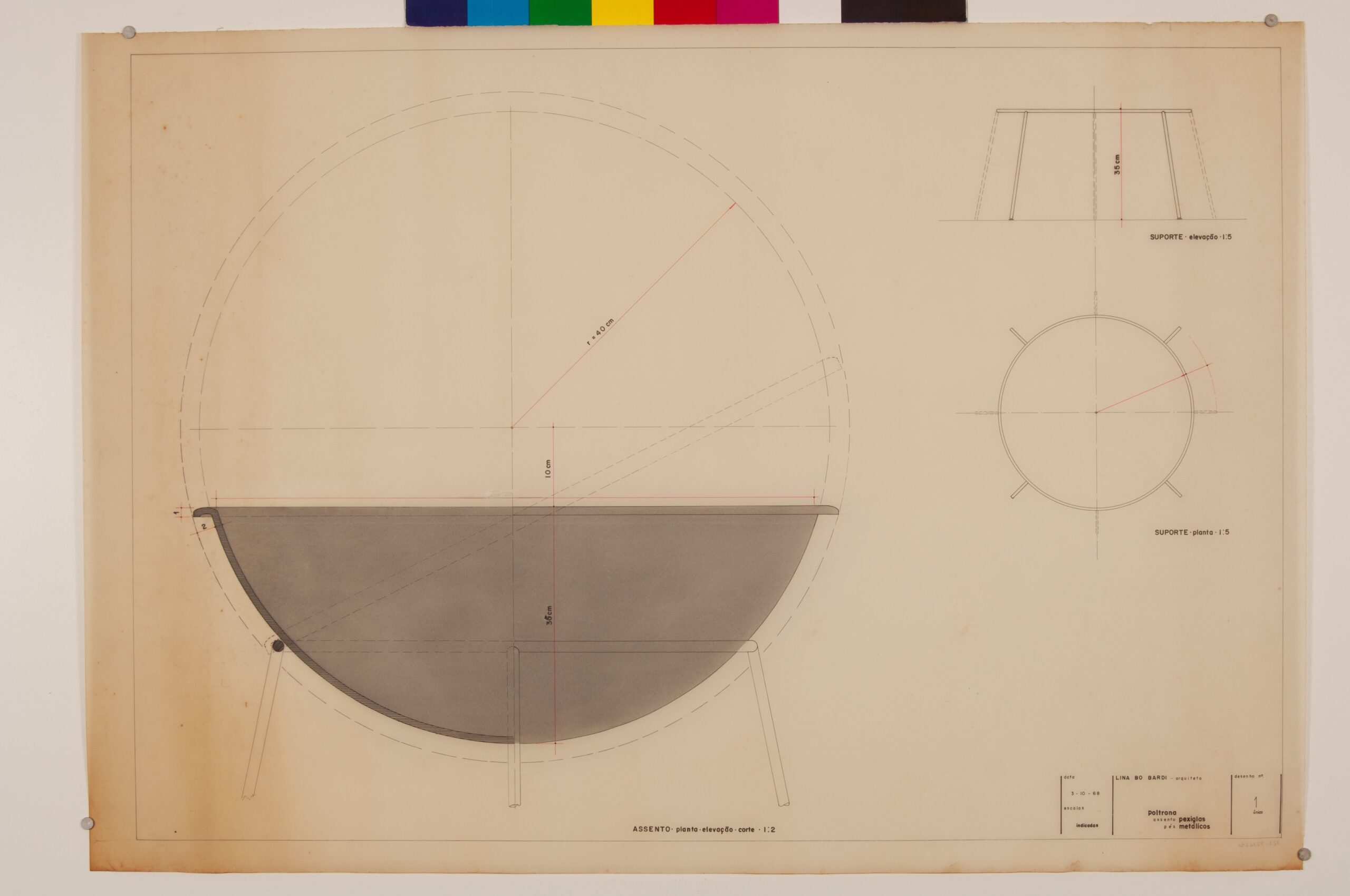

Plans, section, and elevation of the Bardi’s Bowl. Image courtesy of Instituto Bardi.

Bo Bardi became a Brazilian citizen in 1951 and wholeheartedly embraced her adopted country. She spent about five years living and working in the impoverished city of Salvador in Bahia in the late 1950s and early ’60s. The experience proved fundamental for her, as she gained a newfound respect for Brazil’s native materials and architectural aesthetic. She began designing what she called “arquitetura povera” by using local materials to create simple forms and repurposing historic buildings. She designed the Bahia Modern Art Museum and Folk Art Museum, the Gregório de Mattos Theater, the Casa do Benin, and Coati Restaurant in Salvador as well as the SESC Fábrica Pompéia in São Paulo. But perhaps her most innovative project from this period is the Teatro Oficina, which completely subverts bourgeois theatre design, placing performers on an elongated internal street and spectators on a light scaffolding structure above it, thereby obliterating the traditional performer-audience relationship.

Lina Bo Bardi’s Casa de Vidro, 1952. Photo by Francisco Albuquerque; courtesy of Instituto Bardi.

SESC Fábrica Pompéia in São Paulo. Photo by Leonardo Finotti

“If there is one architect who embodies most fittingly the theme of the Biennale Architettura 2021, it is Lina Bo Bardi,” Hashim Sarkis, the Biennale’s curator, said in a statement announcing the award. “Her career as a designer, editor, curator, and activist reminds us of the role of the architect as convener and importantly, as the builder of collective visions.”