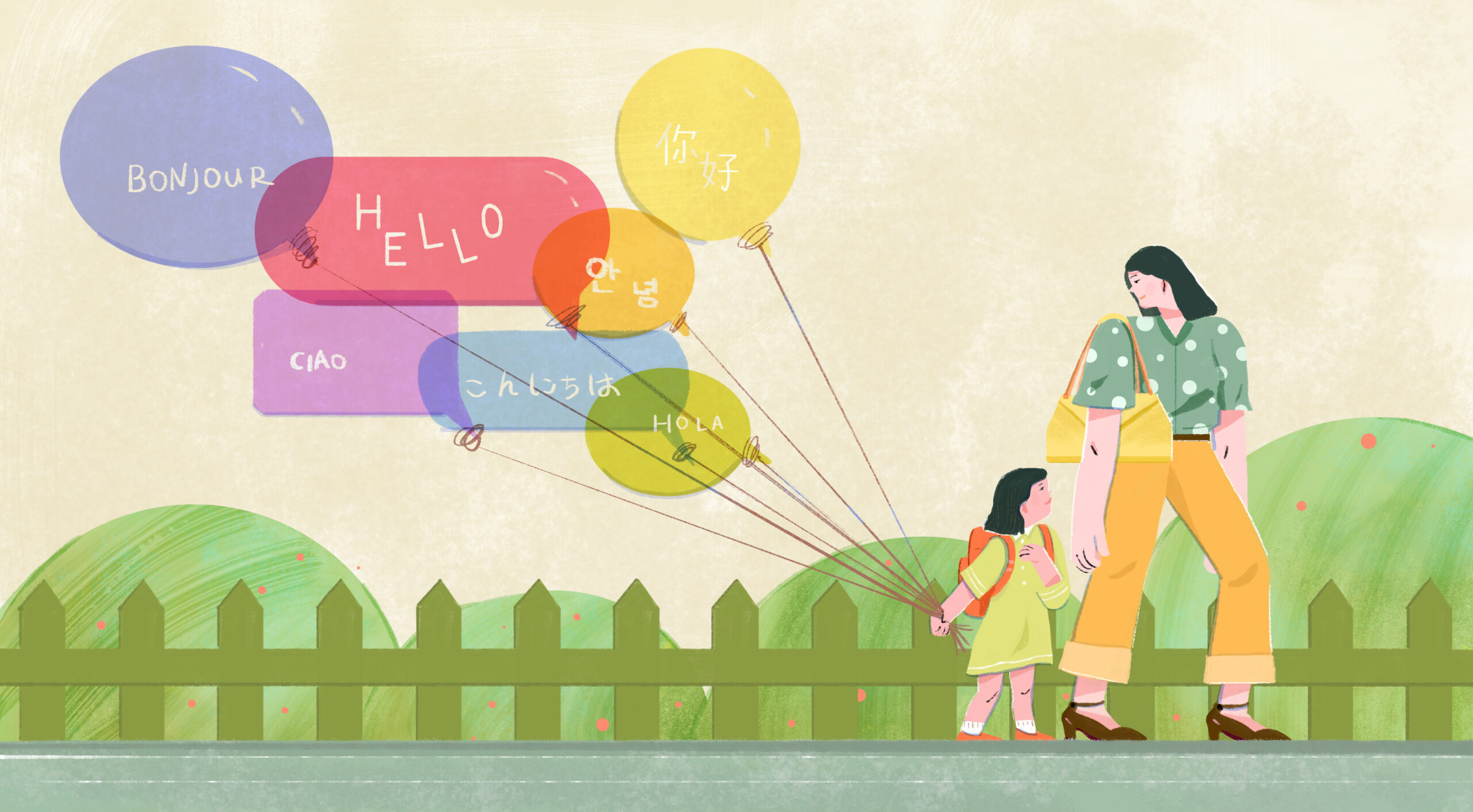

Why Should We Speak and Teach Our Children Foreign Languages?

Polyglotism.

Jianan Liu / jiananliu.com This art work is copyrighted and may not be reproduced or distrubuted without consent of the author. Notice: Remvoing copyright notice is a crime

Two is better than one; indeed three is better than two. When we are referring to languages, that is. Knowing more is proven to be good for our health, strengthens our cognitive abilities, and is also said to slow down the progression of degenerative diseases. Research done at Toronto’s York University indicates that speaking multiple languages significantly slows the cognitive impairment caused by Alzheimer’s. As Canadian psychologist Ellen Bialystok, research director points out: “It seems that speaking more than one language helps to control the damage caused by the disease, allowing these subjects to maintain brain function longer.” Around the world, more than half of people—estimates vary from 60 to 75 per cent—speak at least two languages.

Born in Bologna in 1774, Giuseppe Gasparo Mezzofanti, a cardinal and hyperpolyglot (someone who knows at least eleven languages) was said to have known 70 languages. Charles William Russell, scholar and biographer of Mezzofanti, described the Italian cardinal as able to speak Italian, Hebrew, Arabic, Coptic, Armenian, Turkish, Albanian, Persian, Maltese, ancient and modern Greek, Latin, Spanish, Portuguese, French, German, Swedish, English, Russian and even Polish, Hungarian, Amharic, Chinese, Hindi, Gujarati, and Romanian “with rare excellence.” The list continues with another 30-plus languages Mezzofanti spoke “with less familiarity.”

Reading about Mezzofanti’s abilities can trigger conflicting reactions. First, admiration—a mnemonic ability, combined with the dedication of study; the second is to turn up your nose, asking, how does one get a memory of that type? Keep in mind Mezzonfanti lived in the 18th century, not the modern-day era of interconnection, multiculturalism, the internet, globalization, and low-cost travel (even now, you would be hard pressed to find someone adept at speaking 70-plus languages).

What type of life does someone who speaks 70 languages live? Are they born with the ability? To what degree does the nature vs. nurture argument come into to play? Mezzofanti spent years studying at pious schools where many foreign missionaries and exiles of the Papal States passed the time. In a very long New Yorker article, journalist Judith Thurman accompanied Luis Miguel Rojas-Berscia, a 27-year-old hyper-multilingual doctoral candidate in psycholinguistics, to Malta to learn Maltese. The piece highlights some neural characteristics thought to be closely related to language acquisition and retention. The mnemonic ability is primarily connected to a certain plasticity of the brain.

Speaking a language—having memorized the words to refer to the things of the world—has to be coupled with being familiar with the culture that expresses itself through the words. I do not speak French without knowing France and its worldwide influence. I do not speak Italian without having an idea of what Italian culinary culture is (of course, it helps that my parents are Italian). Culture and language are closely connected, and it is difficult to separate them. In learning a language, we refer to the culture in which it has evolved. Language is never mere code. Each language has ambiguities that can only be filled with practical—in linguistics one would say pragmatic—knowledge of the world. In layman’s terms, you need the experience.

Speaking a language—having memorized the words to refer to the things of the world—has to be coupled with being familiar with the culture that expresses itself through the words.

Picking up a foreign language has been a thing during these past few months of sheltering in place. (How much sourdough can one bake?) Language-learning companies recorded all-time highs in new user sign-ups during lockdown, with Duolingo reporting a 108 per cent increase globally. Learning a language has never been easier, and the time to take on an intellectual project is right no matter when one begins. English is by far the most commonly studied foreign language, with current estimates that 1.5 billion of the world’s 7.5 billion inhabitants speak English, 20 per cent of the Earth’s population. To be monolingual, as many native English speakers are, is to be in the minority and perhaps to be missing out.

I was born in Vancouver. My native tongue is English. Even so, as an immigrant parent, my mother had me in elocution lessons to ensure the delivery of the language she learned as her second language would be as masterful as possible. Growing up, we spoke English at home. For my generation, it was about fitting in. When I had children of my own, I decided I would speak to them in Italian—the opposite of what my parents had done. Years passed and the times had changed. Languages are a cultural cachet. To quote friends whose native tongue is Slovakian, who learned English upon moving to Canada, and whose children speak fluent Arabic after having lived in Qatar for years, “languages are like hidden ammunition to fire at any time.”

It is never too late to learn another tongue. Seventy is probably too ambitious a goal. Take on one—it’s a worthwhile investment of time. And why not talk—parlare, sprechen, hablar, parler—in as many languages as you can?

________

Never miss a story. Sign up for NUVO’s weekly newsletter here.