Hito Steyerl’s This is the Future at the AGO

Future’s past.

Hito Steyerl: This is the Future, on now at the Art Gallery of Ontario (AGO) is full of loops; one finds themselves strolling back, at the conclusion, into the room they started in. The first room presents a film on loop called Liquidity Inc., which focuses on waves and water—a fitting entrance, for Steyerl has a style that washes over you with force and repetition.

The show, curated by Adelina Vlas, displays works created by Steyerl over the last fifteen years. The evolution of her aesthetic is both startling and satisfyingly predictable. An early piece, November (2004) grapples with Steyerl’s childhood friendship to the assassinated Kurdish political activist, Andrea Wolf. The project splices a silent movie they made at the age of 17 with clips of pulp movies, documentary footage of Andrea Wolf in the political media, and Bruce Lee’s funeral.

This mixing of past and present relate to the title of the exhibition, which includes a complex declaration. If this is the future, time has caught up to itself. Or perhaps the present is moving too quickly and the future is moving too slowly. If this is the future, something must have broken somewhere along the line, for this is surreal. It is the very boundaries of past and present, real and contrived, that Steyerl’s work struggles to understand. The ambiguity of this makes you think, and that’s productive.

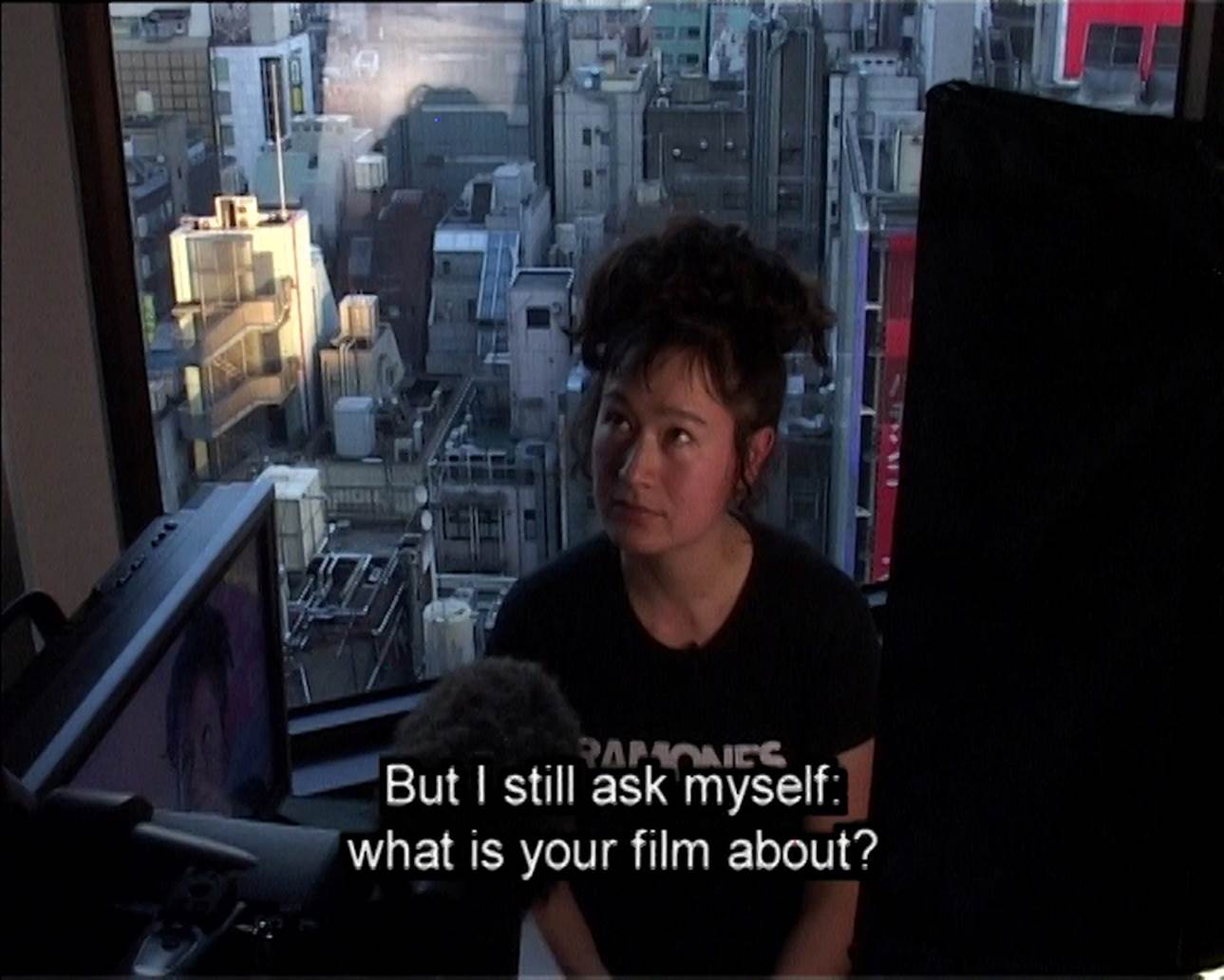

In Lovely Andrea (2007), a piece documenting Steyerl’s attempt to recover photos of her from her brief career as a rope-bondage model, Steyerl inverts footage of a woman suspended by rope. With the video flipped, the woman looks like she is floating. It is still sensual, but it is no longer clear whether she is free or in bondage.

Lovely Andrea (2007).

Later works, such as HellYeahWeFuckDie (2017) show a shift in orientation toward the future. In this piece, we watch digital robots get knocked down by rocks that are thrown at them. Nothing about the piece reads as realistic. It is clearly a digitally created scene, and yet, the viewer might feel agony on behalf of the robots.

Steyerl’s work is anchored in its commitment to both invention and compassion. The works are brisk, sharp, jocular, and contrived, but none of this makes them insincere. Instead, we can see how Steyerl’s art turns in on itself, and on art in general, to interrogate exactly what it is doing and how it relates to its environment.

Two pieces, both unlike the rest of the longer films, demonstrate this interrogation poignantly. First, Freeplots is a collection of plants potted in crates taken from the Milky Way Garden, a public garden in Toronto’s Parkdale Library. The project mixes plants with audio recordings of the community tending to the garden, most of whom are Tibetan women. The audio recordings are buried in the crates themselves.By introducing a Toronto-specific, living art piece to the AGO, the German Steyerl ties her body of work to the city.

Second, Strike (2010) is a short movie that depicts Steyerl cracking a TV screen. We watch as she gently strikes the screen, garbling the pixels and leaving an irreparable mark on the display. With this act, we watch as she destroys the very vehicle by which her art moves.

The mix of material and digital is the future, certainly. But the way we mix the two and how we look at the past through the digital, can be wrought in different ways—often through art—as Steyerl’s exhibition shows.

HellYeahWeFuckDie (2017).

On now until February 23rd 2020.

_________

Never miss a story. Sign up for NUVO’s weekly newsletter here.