An Organization Takes Steps to Revive Ancient Agricultural Systems in Mexico

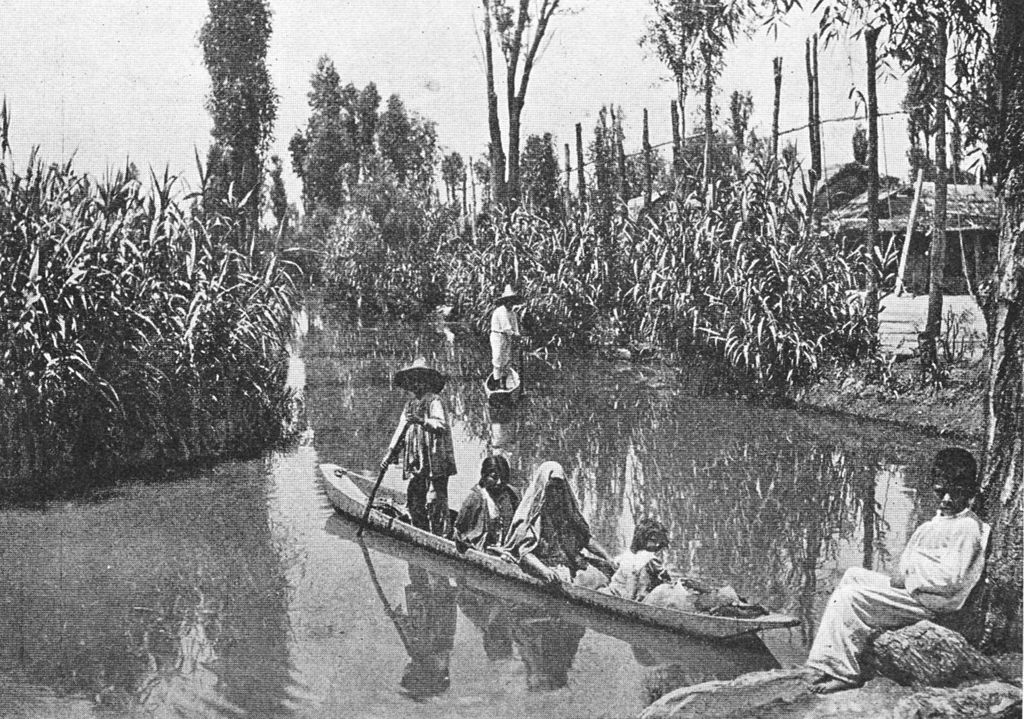

The Venice of Mexico.

On a mid-week morning, far from the traffic and turmoil of daily life in Mexico City, a few women cook corn tortillas over an open fire.

In Mexico, there’s nothing remarkable about that, of course, except that these women are working on a small plot of land in what was once a vast network of islands and canals.

On the outskirts of Mexico City, the floating gardens of Xochimilco preserve the last remnants of the city’s pre-Hispanic agricultural system.

“Even before the Aztecs, there were people living here,” says the man sitting next to me as we cruise along a tree-lined canal on our way to Chinampas del Sol.

Needing more land to grow food, the people who preceded the Aztecs created artificial islands on Lake Xochimilco and other lakes that once covered much of the valley where modern-day Mexico City sprawls.

When the Spanish arrived in 1519, they drained many of the lakes, and the ancient technique of growing crops almost disappeared with them. In recent decades, Xochimilco—it means “place of flowers”—is where locals have come on weekends to cruise the picturesque canals in brightly painted flat-bottom boats, listen to floating mariachi bands, and enjoy picnics. But increasingly, this place is being recognized as an important link to both the city’s past and its future.

Needing more land to grow food, the people who preceded the Aztecs created artificial islands on Lake Xochimilco and other lakes that once covered much of the valley where modern-day Mexico City sprawls.

Stepping off our boat, the land is firm underfoot, and it’s amazing to think that people created these islands by hand, just like the islands of Venice.

In this case, mud and debris from the bottom of the shallow lake were scooped up and contained with branches to form small rectangular plots. Willows and other water-loving trees were planted along the edges of the islands to further stabilize them.

These chinampas formed the basis of an ancient agricultural system that grew a lot of food for a lot of people. It’s estimated that about a million people lived in this valley before the Spanish conquest.

Today, the remaining chinampas are being revived by locals who value this organic and highly productive method of farming.

An organization called Yolcan has been instrumental in supporting people who want to farm and helping them get fair prices for their produce.

A modern day Chinampa.

“We had a guy selling bubble gum in the subway; now he’s working here,” says Alejandro Mendoza, our guide, as we walk between rows of flowering kale that reach almost to our shoulders.

Leading us to a patch of what appears to be barren soil, Mendoza shows us the ingenious method that the farmers use to start and separate seedlings.

Bending down, he breaks off a chunk of black earth that’s about the size and shape of those flimsy black plastic pots sold in six-packs of seedlings in gardening stores in Canada.

But here, they don’t need plastic.

The farmer simply scoops a bucket full of muddy sediment from the bottom of the canal, lets it dry in the sun, then uses a rake to mark squares on the surface. After that he pokes a hole in each square and plants a seed. When the seeds sprout, the farmer breaks off the individual squares of hardened soil—called chapins—and transplants them in his field.

One of the remaining chinampas in Xochimilco from the water.

“It’s highly probable that the Mexica and Aztec people used this farming method,” explains Mendoza.

When Xochimilco was recognized as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1987, along with the historic centre of Mexico City, the international agency described the chinampas as “one of the most productive and sustainable agricultural systems in the world.”

“I feel pretty excited about this kind of knowledge being preserved nowadays, especially in a context like Mexico City,” says Mendoza.

Some of Mexico City’s top chefs are just as excited. Those buying directly from Yolcan farmers include Eduardo García of much-loved Maximo Bistrot.

García says the difference in taste between conventional produce and Yolcan’s is huge.

“It’s difficult to explain since currently, people don’t know what a natural product should really taste [like]. In Yolcan, the harvest times are longer because they don’t have chemicals, the taste is very different.”

And now it’s time for us to enjoy today’s harvest. First we join the women making tortillas and take turns pressing the last of them and turning them onto the grill. Then, at long tables under a shady canopy, we enjoy a colourful salad of leafy greens, spicy radishes, sun-warmed tomatoes, and other vegetables harvested mere hours ago.

The tortillas have been transformed into quesadillas with cheese made from a local farmer, and we smother them with spicy red and green salsas.

Simple, delicious, and local food. What more could one want?

________

Never miss a story. Sign up for NUVO’s weekly newsletter here.